Theirs was the American Dream

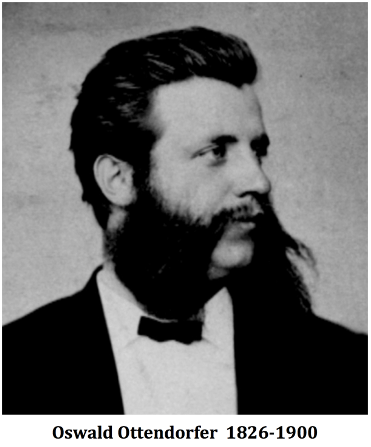

Oswald Valentin Ottendorfer 1826 - 1900

(Anna Behr's second husband. No children. Related by marriage.)

OSWALD OTTENDORFER, journalist, public leader and philanthropist, is one of those progressive and high minded sons of old Germany, who have attained in the life of this metropolis during a long professional career not only the affection of large masses of their own countrymen now resident here but the respect of the native born population.

He is a native of Zwittau the capital and largest town in the Svitavy District in the Pardubice Region of the Czech Republic, where he was born, Feb. 26, 1826. His father, Vinzenz Ottendorfer was a manufacturer of wooden goods in excellent circumstances.

Having received a sound preliminary training, Ottendorfer became a student in the University of Vienna for a year, during which time, being destined for a public career, he paid especial attention to jurisprudence.

After a short stay in Prague, where he learned the Czech language and studied Law, he returned in 1848 to Vienna and at once espoused with all the energy of an ardent nature the movement among the patriotic youth of Austria to secure by agitation, and force if necessary, the liberties of the people.

An uprising in March 1848, in which Ottendorfer was prominent, led to the downfall of the Metternich government. Thus launched upon a public career and baptized in the struggle against despotic power, and now desiring military experience, he soon became a volunteer in the Von der Tann corps and took part in the Schleswig-Holstein war against the army of Denmark.

Oct. 5, 1848, the students of Vienna rose in arms against the detachments of the Austrian army then in the city, the local force having been weakened by the departure of several regiments to Pesth to take the field against Kossuth. Upon that occasion, Ottendorfer served as first lieutenant in the battalion of the late Robert Blum.

Oct. 5, 1848, the students of Vienna rose in arms against the detachments of the Austrian army then in the city, the local force having been weakened by the departure of several regiments to Pesth to take the field against Kossuth. Upon that occasion, Ottendorfer served as first lieutenant in the battalion of the late Robert Blum.

The students drove out the troops, to be in turn, a few weeks later, themselves overpowered by the Austrian forces, who, after a severe battle, regained the city. Of the few students who escaped in safety from the Austrian capital, Ottendorfer was one. After three days and nights of hiding in the chimney of an old book store, the young man made his way to Saxony, only to return, under an assumed name, with others, to the capital of Bohemia to concert another uprising. The movement was discovered, however, and the students fled to Dresden, where, in May 1849, they took part in another revolution and held possession of the city for nearly a week. This was a serious affair and ended in the recapture of the city by Prussian troops, hastily summoned by the King of Saxony. The students sought to escape to Thuringia, but those who left the city were all taken. Like their compatriots in Vienna, many were put to death and others sentenced to long imprisonment.

Ottendorfer escaped by an accident. He had spent several days and nights without rest and, owing to physical exhaustion, did not awaken until noon, when he found Dresden full of Prussian soldiers. After a few days of concealment, he managed to reach Frankfort unobserved. But agitation continued and Ottendorfer would have taken part in the battle of Waghaeusel had he not been stricken down with typhoid fever in Heidelberg. His last exploit, undertaken after three months of hiding, was the rescue of Steck, who had been sentenced for life and incarcerated in the castle of Bruchsal. With his comrades and Steck, he escaped safely to Switzerland.

At twenty-four, Ottendorfer had passed through scenes of tragic adventure, such as fall to the lot of few men of his age. His hopes had been frustrated and he then resolved to begin life anew in Vienna. From this he was dissuaded by friends, who predicted certain death should he return to the scene of his revolutionary labours.

In this emergency, he finally decided to immigrate to the United States. With the aid of friends, he passed through Poland and in 1850, landed in New York City. His means were small but he found a large, liberty-loving, German element in the city, which welcomed the young agitator with great cordiality.

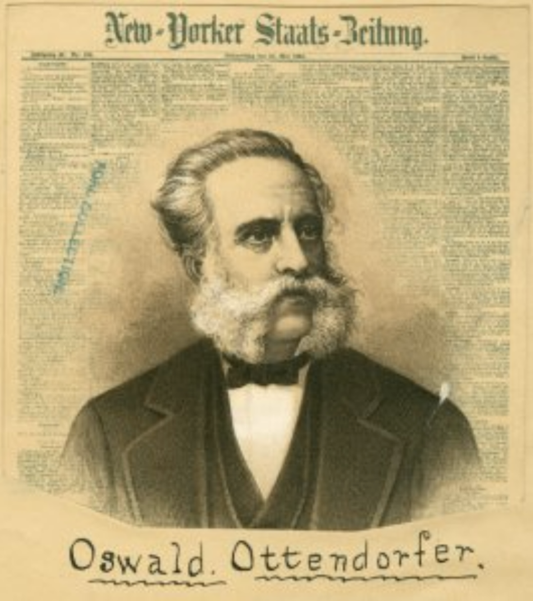

Promptly securing employment in the business office of the New Yorker Staats-Zeitung, Ottendorfer now found a field for the exercise of his undoubted abilities, which promised success; and he applied himself to seconding the efforts of the proprietor, Jacob Uhl, in the management of the newspaper. Founded Dec. 24, 1834, as a weekly on Nassau Street, and printed in the German language, the Staats-Zeitung had been bought in 1844 by Mr Uhl, who, with the aid of his wife, a woman of superior mind, had made it a daily and already given it the position of the leading German journal of the city.

Mr Uhl died in 1851 and Mrs Uhl then assumed the management. She was a woman not only of unusual sweetness and beauty of character but intellectual, energetic and sagacious. She foresaw a great future for the Staats-Zeitung, refused various offers to sell, and, aided by Ottendorfer, conducted the paper for eight years with constantly increasing success.

In 1859, Ottendorfer married Mrs Uhl and thereafter became the leading spirit in the management, although for many years he enjoyed the co-operation of his competent and distinguished wife. In 1881 failing health finally compelled Mrs Ottendorfer to relinquish her share of the duties of management. She died April 1, 1884, making many public gifts and leaving $30,000 to be distributed among the employees of the Staats-Zeitung.

During the nearly half a century of his connection with the Staats-Zeitung, Ottendorfer contributed materially toward making his paper a successful property, a strong influence for pure government and the leader of the German element in the population of the city against inefficient and demoralizing local rule.

A Democrat in political faith, although now independent in local affairs, he was a supporter of Samuel J. Tilden and Grover Cleveland and an advocate of sound currency, civil service reform, a moderate tariff and the improvement of the public schools. As a member of the Committee of Seventy, he joined in the successful effort to crush the Tweed ring.

For one year, he served as an Alderman of the city, but refused the salary of $4,000, considering it out of proportion to the services expected, and also refused nominations for Mayor more than once. The large stone office building at the corner of Park Row and Centre Street, which was the home of the Staats-Zeitung, at one time included among its tenants the tax Department of the city government.

The hostility of Tammany, which Ottendorfer had the honour to incur, in consequence of his attacks upon corrupt municipal rule, finally led that organization to remove the department to another location. This puerile effort to injure a public spirited and courageous man met with the public ridicule which it deserved and proved absolutely powerless as a punishment.

Mrs Ottendorfer during her lifetime, and Mr Ottendorfer since, both became conspicuous for their generous use of the wealth brought them by their very successful newspaper. Among their gifts have been more than $500'000 to the Isabella Home for aged men and women and chronic invalids at Fort George in this city, founded in memory of a daughter of Mrs Ottendorfer; $500'000 from Mr Ottendorfer to build and endow a school, orphan asylum and other institutions in his native town; $50'000 for the Ottendorfer Free Library on Second Avenue; $100'000 to the German Dispensary; $75'000 to a pavilion in the German Hospital and a large sum for other institutions. For her generosity, the Empress of Germany conferred upon Mrs. Ottendorfer a gold medal in 1883.

Few, if any other of the adopted citizens of the United States have made such a remarkable record for success and good citizenship as the subject of this biography.

Mr Ottendorfer is a member of the Manhattan, Reform, Century, City and Commonwealth clubs, and now spends several weeks every summer in visiting Europe.

HALL, H. (America's successful men of affairs. 2 v. 1895-96)

Ottendorfer House in Zwittau – a red-brick historicist building with a tower, it is one of the symbols of the town, built in 1892 on the site of the cottage where his was born.

It originally housed the public Ottendorfer Library, until the Second World War the largest and most modern German-language library in Moravia (what is left of the collection is now located at the City Museum and Gallery), later a city cultural centre.

Tenement Museum Oswald Ottendorfer for Mayor!

It’s election day in New York City, and here at the Tenement Museum, we’re endorsing our own candidate – Valentin Oswald Ottendorfer! In 1874, Ottendorfer, a German immigrant and resident of the Lower East Side ran for mayor of New York City as an independent, but we think he has many qualities that are still electable in 2013.

He’s an intellectual, a veteran and hero! – Ottendorfer studied Classics, law, and Czech in his native Germany, and finished his studies in Padua, Italy. After completing his studies, Ottendorfer joined the Germany army and fought in the First Schleswig War, or the Three Days War; a war between Germany and Denmark over which country should control the Duchies of Schleswig and Holstein.

He has a revolutionary past (but age has made him moderate)! – After returning to Vienna, Ottendorfer found that the city was going through a revolution; Austrian soldiers were going to invade Hungary, who was rebelling against the oppressive authoritarian Austrian Empire. Ottendorfer joined up with the revolutionaries, mostly students and liberals, who had taken control of the government. Many of the revolutionaries were captured or killed, but Ottendorfer escaped to continue his revolutionary ways across Germany and Austria, and eventually immigrated to the United States.

He’s a self-made man who overcame adversity! The youngest of 6 children of an upper-middle class manufacturer, Ottendorfer found little work after first arriving in America, for he spoke six languages, but none of them were English. He began to work as a day laborer. He eventually found employment at the Staats-Zeitung, a German language newspaper in New York City, where he worked his way up to an editorial position. Ottendorfer eventually married the widow of the previous editor and took control of the paper.

He is generous with his wealth and is a philanthropist! He donated $300,000 to build an academic institution in Austria (he cares about the people back home!) and built a home for indigent men, what today we would call a homeless shelter, on Long Island (he cares about the less fortunate!). In New York City, he established the Ottendorfer Free Library on Second Ave (he cares about education!). The Library, now part of the New York Public Library system, is the oldest NYPL in its original building.

The library that Ottendorfer built for the neighborhood, now owned by the New York Public Library.

He’s bipartisan! – Ottendorfer never registered for a party but had strong Democratic leanings. Of course, the Democratic party of the 1870’s was rather different from today’s Democratic party. They tended to favor small government, westward expansion, opposition to a national bank, greater equality for white men, but on the flip side, discriminatory policies (many Southerners were Democrats, and were angry about the Civil War and Reconstruction). However, Ottendorfer would have been described as a “Union Democrat,” a Democrat who opposed the Civil War and condemned slavery, as opposed to a “Peace Democrat,” or “Copperhead,” the groups that sympathized with the Confederacy during the Civil War and demanded immediate peace.

He’s bipartisan! – Ottendorfer never registered for a party but had strong Democratic leanings. Of course, the Democratic party of the 1870’s was rather different from today’s Democratic party. They tended to favor small government, westward expansion, opposition to a national bank, greater equality for white men, but on the flip side, discriminatory policies (many Southerners were Democrats, and were angry about the Civil War and Reconstruction). However, Ottendorfer would have been described as a “Union Democrat,” a Democrat who opposed the Civil War and condemned slavery, as opposed to a “Peace Democrat,” or “Copperhead,” the groups that sympathized with the Confederacy during the Civil War and demanded immediate peace.

He has political experience! – Ottendorfer represented the State of New York in the Electoral College several times, and supported Stephen Douglas’ failed presidential bid in 1860. He also served the Lower East Side as an alderman, what we would today call a City Council member, from 1872 to 1874.

He ran on a platform of reform! – As an 1874 mayoral candidate, Ottendorfer advocated civil service reform, the eradication of corruption (Ottendorfer helped to expose 1873 Mayor William Havemeyer’s various and sundry deeds done in the name of Tammany Hall) and improvements in public schools, two topics that candidates today are still dealing with!

Of course, Ottendorfer did not win his mayoral bid – he lost (quite miserably) to the Tammany Machine that controlled local elections for decades – and he returned to journalism and philanthropy until he moved back to Europe in his later years. But we can see in him a politician that truly wished to make life better for all New Yorkers, despite race or social class. So remember that if you can’t decide who to vote for today, you can always write in Valintin Oswald Ottendorfer!! (Maybe he should make his name easier to spell if he’s going for the write in….)

If you live in the New York City area and are registered to vote, check this link to check your polling place, and get out and vote today!

– Posted by Lib Tietjen

Svitavy News

OTTENDORFER-ERINNERUNGEN.

Ottendorfer's escape and arrival in America

The well-known Russian revolutionary Bakunin also played a certain role in Ottendorfer's life. On his way home from Schleswig-Holstein, in whose liberation struggles against the Danes he had participated, Ottendorfer made the acquaintance of Bakunin in Breslau in the late summer of 1848. After the suppression of the Vienna Uprising by the Croats on 28 October 1848, Ottendorfer, after hiding in Vienna for a few days, fled across the Saxon border with the intention of resuming his studies at the University of Leipzig. But also in Saxony the flames of turmoil blazed. On his crusades through Europe, Bakunin had come from France via Prague, where he had taken part in the Slavic Congress, to Dresden, where in May 1849 there was an uprising that resulted in the king's flight from Dresden. Drawn into the revolutionary movement by Bakunin, who was a member of the revolutionary government in Dresden, Ottendorfer took part in the fierce struggles which were delivered to the invading Prussians on 9 May 1849 and which ended in the complete defeat of the revolutionaries. Ottendorfer escaped capture again only by a lucky coincidence and fled to Jena, where he was taken in by a Viennese friend, the physician and later physician Dr. Julius von Hausen, who later also went to America and settled in New York. Here he was seized by a serious illness and when he left the infirmary, the "Spring of Nations" was over. For even in Baden, where he initially turned, the revolution was bloodily suppressed and Ottendorfer was faced with the iron necessity to give up the political activity that had become useless and to seriously approach the question of the future shaping of his life's fate.

He went to Heidelberg, where he was eager to pursue his studies in 1849 and 1850.

He returned home unexpectedly in September 1850. His mood was desperate, because he expressed the decision to surrender to the authorities and let his fate befall him, but his relatives talked him out of it. Since the danger of discovery lay closest to Svitavy, Ottendorfer had not turned to his hometown, but to Brno, where he was taken in by relatives, namely the Friedrich family. The situation was all the more dangerous for him because the arch-revolutionary Bakunin, who had been sentenced to death in Germany, then pardoned and extradited to Austria, was put on trial here, during which Ottendorfer's relations with Bakunin were discussed. The situation therefore became untenable for him. Already Frederick's house searches had been carried out, a further hesitation could be fatal and so it came with the most laborious cooperation of Frederick to escape. That this succeeded is probably only due to Frederick's prudent arrangements. After all other preparations had been made, he bought the ticket at the station, got into the car himself to deceive the watching police, opened the opposite door and let in Ottendorfer, who was waiting on the other side of the train. He gave him the ticket, shook his hand and left the station staffed by scouts, which was only possible because the station had a different shape then, as it does today. Ottendorfer was happily in the train, which initially led him towards his hometown. What may have been his feelings when the train stopped in Svitavy. Although he had to assume that his father, who was aware of his son's passage, was at the station, he could not dare to show himself at the window, because it was here that the danger of being recognized and arrested by scouts was greatest. So he drove through Svitavy without a parting greeting from his parents, whom he did not see again, because when he came to Svitavy for the first time in 1869, they were dead. Ottendorfer happily reached Bremen, where he boarded the sailing ship "Elisabeth" on 20 September 1850, which brought him to New York after a 36-day stormy and dangerous crossing. From the Bremer Rhede he wrote a letter to one of his brothers, in which it says: "It is impossible for me to stay in Austria, as a political refugee in Switzerland or England I do not want to live; so nothing else but America is superfluous to me. In the last sight of the European coast, I protest against the opinion that I am leaving my fatherland as a result of despair for Germany's future. I leave because I have to and return as soon as it is possible. I believe I have done my duty and will take it up again as soon as I can."

Ottendorfer describes his situation when he arrived in America and how he thought about it in an essay he published in his later years on immigration, which states:

"I remember very vividly the impressions I received when I arrived in the United States, about 40 years ago. I had already become a great admirer of American institutions through what I knew about American institutions from my studies. The ship that brought me over had barely docked at the dock when I ran up the next street. On Broadway, standing near the Astor House, I watched the passers-by. According to their appearance, it was mostly men who worked for daily bread, but almost everyone had the attitude of a sovereign. Her eyes seemed to say, "I'm not behind anyone; there is nothing too big or too high for me not to reach it, and I intend to break ground." Since I could not speak English, I saw that it would be impossible for me to get a job in which I could use my university knowledge, and since I had almost no money, after days I accepted a job as an ordinary worker in a factory, although I had never done the slightest manual labor in my life. After a few hours my hands were full of blisters, and a few hours later full of bloody calluses; but I was fueled by the energy I had perceived in the eyes of the men when I arrived and continued in my work without being discouraged by pain or difficulty. I had received the baptism of the real American spirit and never in my life was so proud of anything as the calluses my work caused me."

Transcript from the Svitavy museum website

Zwittau compatriot Valentin Oswald Ottendorfer (*1826) was not bedded on roses. He came from a cloth-making family – cloth-making was at the height of its fame at the time – and he was thus materially secure. He had a myriad of siblings, eleven, but only six of them reached adulthood. Oswald must have been an astute child, he was destined to study.

He studied first at the Piarist Gymnasium in Litomyšl, later at the University of Vienna and Prague. The subjects of philosophy and law formed his worldview and he was formed by the newly emerging bourgeois society. He smelled of democracy and general values of freedom and did not give up these principles until the end of his life. In 1848 he fought under the banner of the student legions on the barricades and spent the revolution on the streets of several German cities and in Vienna. The Austrian police relentlessly persecuted such "democratic elements" and a profile issued against the criminal prompted him to emigrate to the USA.

Without saying goodbye to his family, without training and knowledge of the English language, the young man arrives in New York Harbor. He started as a day wage and unskilled worker and at night he learned a new language and swallowed the atmosphere of the American milieu. With the help of his friends, he quickly became a typesetter in an influential German diary New Yorker Staats-Zeitung, which belonged to the German emigrants, the Uhl family. Ottendorfer progressed professionally in the editorial office, glossed over political life in America and it seemed that he was gaining a firm foothold in his new home. In addition, luck was at his side. At the end of the 50s, the widow of the newspaper owner, Anna Uhl, fell in love with him. She was a few years older, but full of energy, experience and charm. Ottendorfer also adopted six descendants from Anna's marriage. At that time, Oswald became seriously ill, he had to heal himself in European seaside resorts, but he could not visit his hometown of Svitavy. Only the amnesty opened the borders and the Austro-Hungarian compromise also brought new ideas. At the end of the 70s, the Ottendorfers became respected American citizens. He, as a member of the Democratic Party, almost became the mayor of New York (he declined the candidacy), and she stood in the birth of many charitable institutions – orphanages, infirmaries, and hospitals. They coined a motto that still applies today – if you have healthy hands and can work, you have to work! The others are to be helped. They knew what they were talking about.

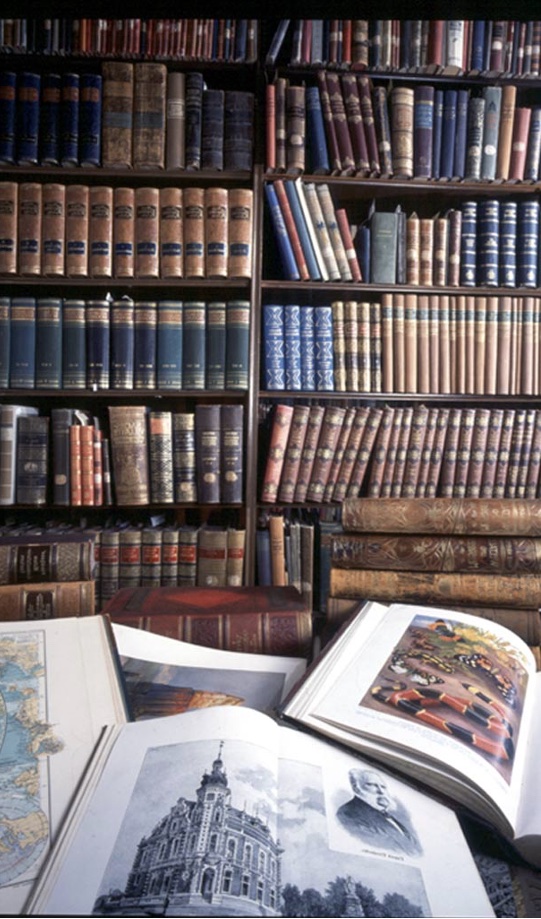

From the 50s of the 19th century, the city of Svitavy struggled with problems in health care, popular education and education. There was no hospital, and the poor found themselves in borderline situations as a result of the economic crisis. For these reasons, the city accepted the offer of financial participation in the construction of the new hospital [o_07] as well as orphanage and infirmary [o_08] from Ottendorfer with great pleasure. In 1886, both institutions were opened with song and sound and with Ottendorfer's participation. In Ottendorfer-Straße stood the orphanage and infirmary and in honor of the patron the bronze bust of the patron was attached in front of the building. The citizens of Svitavy could not have imagined that the institution, which served as a model institution for Moravian cities, would cease to exist in 1892. It took less than two years when a library [o_10] with reading room and lecture hall was built on the site of Ottendorfer's parental home [o_09]. The patron financed the entire construction and also participated in the purchase of the library stock. In the warm days of August 1892, Oswald came to Svitavy accompanied by his stepdaughter. For the second and last time! His legacy, which he left to the city, is still alive today. The library borrowed more than 23 thousand volumes in its depots, making it the largest German public library in Moravia. What lectures and concerts had to be held here. And when President Masaryk visited the city in 1929, the city officials brought him here.

Ottendorfer died in his apartment in New York on December 15, 1900. He is also buried in New York, in Greenwood Cemetery. After his death, a lot of functioning institutions and public schools remained in America. He also liked Svitavy, he remembered his mother – by the way, the statue of motherly love in Svitavy is proof of this. The name Ottendorfer is still often heard in Svitavy today.

Today the library is a mere fragment of one of the largest public German libraries in Moravia.

The library was founded in 1892 using financial gifts from the Svitavy native and patron Valentin Oswald Ottendorfer (1826 - 1900)

The library was provided with an endowment for the purchase of books and became a model for other libraries in smaller towns.

During the first Czechoslovak Republic the library collection was comprised of 22,000 volumes, including periodicals, professional publications, and works of fiction.

Following the Second World War a large portion of the collection was damaged, stolen, and destroyed.

As a remnant of German culture, the collection was designated as worthless and unnecessary. Museum employees managed to preserve 6,755 volumes.

Previous: Anna Sartorius/Behr | Table of contents | Next: Charles Frederic Woerishoffer