Carola Woerishoffer

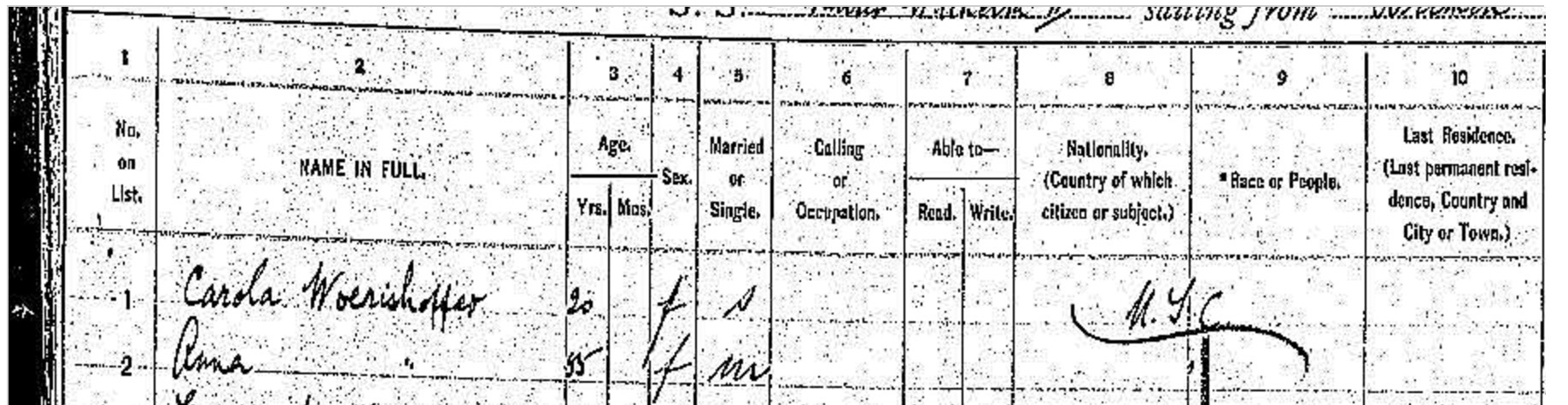

Ship Manifesto - 1905

Letter written by a member (unknown) of The After School Club of America - 1911

There is plenty of discussion about vocations for women, not only magazine articles but whole books have been written to tell us that a woman should have something worth while to do, either in the home or out of it, and so far as I know all sensible people agree with that idea. But every little while a girl steps out into public view, seizes some sort of a new and difficult proposition and makes good to such an extent that she commands attention.

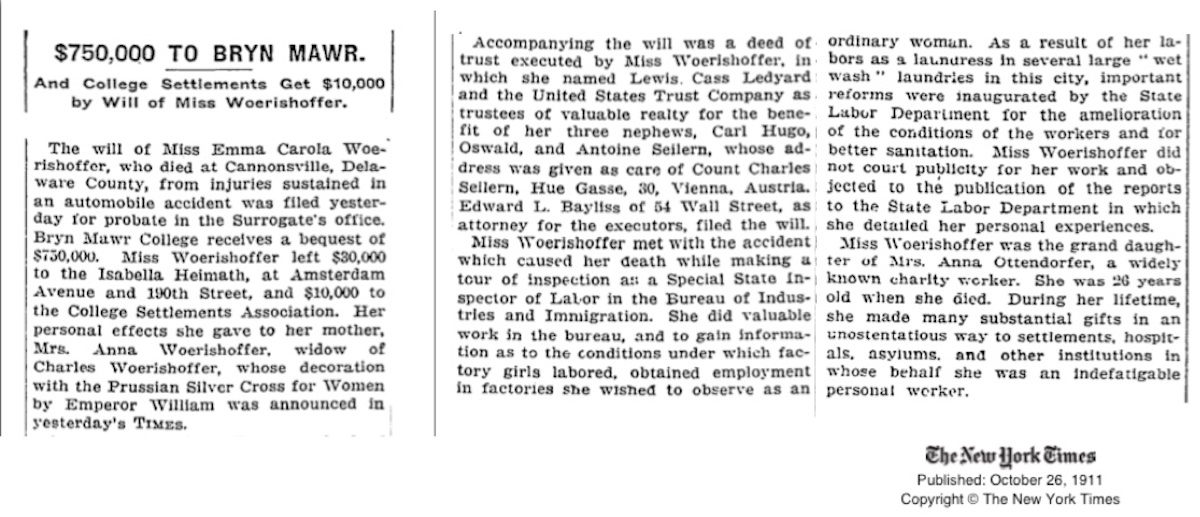

I presume you read not long ago of the gift of $750,000 to Bryn Mawr College by a young girl of New York City, and you probably were amazed at the size of that legacy. But Miss Woerishoeffer gave a great deal more than that to humanity in the course of her short life of twenty-six years.

She was very wealthy, handling an annual income of tens of thousands of dollars, but she hated the inequalities of society. She was determined that her own life should have some meaning, and she went to Bryn Mawr College with the definite purpose of giving herself to social service. That purpose became more and more distinct as her training went on. She would not be turned aside from it, but she kept a singularly open mind all the time, making herself familiar with economic history and with social facts - with all those studies, indeed, that would help her in the service she wanted to give.

When she graduated in 1907 she appeared at once before the social workers of lower New York "to learn and to help," as she said. Miss Woerishoeffer was determined to get at the truth - she would not take second-hand information. She wanted personal contact with the workers, personal experience with the work, so she refused everything but the hardest places, and she found one that I think you will agree with me was about as hard as can be imagined for a girl inexperienced in manual labor in a hot summer.

She went from one laundry to another, keeping the same hours as the other girls, or staying late at night when the work required it, and all this time she was seemingly unconscious of any difference in position, in education, in wealth between herself and her fellow-workers. As she came into close relations with them, she learned their point of view, and she saw why they were permitting intolerable conditions without comment.

One day she called on her friend, Mrs. Florence Kelley, of the Consumers' League, and asked her to take her to lunch. She said, "If you do not, I shall not have any. I undertook when I began working in the laundry to find out as nearly as I could how it would feel just to have the amount of money that I could earn with my strength without skill, and now I have been dismissed for taking the part of an old woman in a scrap with the foreman." Mrs. Kelley tells us that they went out at one o'clock and Miss Woerishoeffer talked until five of the needless hardships of the people among whom she worked. Mrs. Kelley says, "She was aflame with the passion of living and changing the things tha.t ought to be changed."

Presently there came the shirt waist strike of 1909. The police were arresting girls often for slight cause, and it became evident that unless bail were furnished at short notice, hundreds of innocent girls would have to go to jail for an indefinite period. Then Miss Woerishoeffer, fortified with a bond for $90,000, appeared in the court room and announced that she would remain there to see that the girls had fair play. One of the striking incidents of that thirteen weeks is the way she managed the reporters, who were induced to keep their own counsel and protect her from the publicity that she dreaded.

It is hard to write of Miss Woerishoeffer in moderation, but I mustn't dwell on her services in emergencies - industrial and social. It was natural that having learned at first-hand of the exploitation of the poor and ignorant, she should see the need of more investigation and better legislation, and that when the State Bureau of Industries and Immigration was organized, she should offer her services. It was in this service that she lost her life. She was on her way to inspect a labor camp and was driving her own car. She had over-worked, and she was careless about food and rest - a skidding wheel, an over-turned car, and the story is finished. Someone has said that "the state had no enrolled soldier who had responded to his call more promptly, or performed his duties more unflinchingly, or given his life more utterly in the field of battle than this girl gave hers to the cause in which she believed." Miss Tarbell says "rarely at such an age has a purpose been better conceived. She has set a pace for the new soldier in that most splendid of wars - the war against poverty and injustice."

I am sorry this letter is too long, but the subject has been of such interest to me that I could not say less. Miss Woerishoeffer's class at Bryn Mawr College has brought out a little memorial volume which I should be glad to loan you from my own library if you would like to read it.

Yours faithfully,

Editorial in the New York Times, September 15, 1911

A PRACTICAL ALTRUIST

The late Miss Carola Woerishoffer represented, in a high degree, the altruistic spirit so rarely manifested, as it seems, in. a commercial era. The history of her short career would be an interesting study of practical ethics, and an important one too. She was born to wealth, was young and highly connected in the social world. Yet she chose to be a worker for the good of others, and the practical use to which she applied her uncommon talent for altruistic service is what made her career, so remarkable. She did not content herself with the bestowal of alms, or even seek the direction of charitable institutions. On the contrary, she worked in order to learn something at first hand of the pains and burdens of the working people, and she obtained, in the regular way, through civil service examination, an appointment as special Inspector of Labor under the Bureau of Industries and Immigration. Her services in this post of small distinction and much hard work were, we believe, invaluable.

At the time of her death she was investigating the camps and small communities of alien laborers in various parts of the State. She had worked in this way for ten months when she was killed in an automobile accident, and had expended her own money freely but wisely to relieve destitution and sickness. Beyond the comparatively small salary attached to her office, there was ,no possibility of reward. Her services were among the lowly, and through them she was not likely to acquire fame. But she found the required outlet for her unusual gifts, and her compensation was that she could feel she was doing good in a practical way. She was indeed a practical altruist, and her death is a loss to the community.

Sonntagsblatt der New Yorker Zeitung, September 17, 1911

Unter uns Frauen

„Es fiel ein Reif in der Frühlingsnacht“

Der Moloch unserer Tage, das Automobil, hat in dieser Woche, wie in allen anderen des Jahres, seine Opfer gefordert. Eines derselben ist eine junge Dame, deren Hinscheiden an dieser Stelle nicht unerwähnt bleiben kann – aus verschiedenen Gründen. Es ist zunächst eine Pflicht der Pietät, die ich erfülle, wenn ich hier erwähne, daß Frl. Carola Wörishoffer, die Enkelin der Gründerin und einstigen Besitzerin dieses Blattes, der zu Ehren dieses Departement seinen Namen trägt, in bemerkenswerter Weise die Geistesrichtung und die Tathkraft ihrer Großmutter geerbt hatte und wie Mutter und Großmutter das Gefühl in sich trugund in die Praxis übersetzte: daß Reichthum verpflichtet! Das Bibelwort von den Pfunden, die treu zu verwalten sind, ist von ihnen allen hoch gehalten worden.

Müßiggang, Verschwendung, jene Art raffinierten Lebensgenusses, der sich aufdringlich bemerkbar macht und in den Stiefkindern des Schicksals Erbitterung erzeugt, das sind Dinge, die man in dieser Familie nicht an sich heran kommen ließ. Was die ältere Generation in unermüdlicher Arbeit erwarb und durch vorsichtige Verwaltung vermehrte, das wurde von jeher dem Dienste der Menschenliebe geweiht. Und dieses Erbe hatte nach dem Tode der Eltern die Tochter in vollem Umfang angetreten. Es ist nicht meine Absicht, und ist wohl auch nicht nöthig, daß ich heute und hier alles das aufzähle, was zwei Generationen für das Deutschthum der Stadt New York, für all die armen Menschen gethan haben, die trotz besten Willens nicht soweit kommen konnten, in den Tagen der Noth sich selbst helfen zu können. Wohl aber möchte ich in diesem Augenblicke darauf hindeuten, daß Werte der Menschenliebe geübt wurden, von denen nur ich allein weiß, und die kein anderer Mensch je erfahren soll.

Solches Beispiel vor Augen, solche Atmosphäre im Hause, konnten nicht verfehlen, auf das heranwachsende Mädchen einen bestimmten Einfluß auszuüben. Eine natürliche, hohe Begabung, der wie oben angedeutet, auf das Praktische und Thatsächliche gerichtete Sinn, zusammen mit einer sorgfältigen häuslichen Erziehung und einer gründlichen modernen Ausbildung auf dem College Bryn Mawr, wo Frl. Wörishoffer außer den allgemeinen Fächern Sozialwissenschaft und Jurisprudenz studierte, führte sie auf den Weg einer sozialen Wirksamkeit, die sicherlich bahnbrechend genannt werden darf.

Entsagend jeder Annehmlichkeit, die ihre Mittel ihr gestatteten, verzichtend auf jeden Genuß, wie er selbst Minderbemittelten ein Bedürfniß ist, widmete sich Frl. Wörishoffer mit tiefem Ernst und großer Aufopferung dem Studium der Lebensverhältnisse von armen Arbeiterinnen. Sie gab die gewohnte alljährliche Europareise auf, denn sie wollte die Verhältnisse genau kennen lernen, wollte studieren, wie die sommerliche Geschäftsflauheit und Verdienstlosigkeit in materieller Beziehung, und wie die Sommerhitze in den Massenquartieren in hygienischer Beziehung das Leben der Armen beeinflussen.

Frl. Wörishoffer hatte sich namentlich drei Dinge zum Ziel gesetzt: Sie wollte den ums tägliche Brot hart ringenden Schwestern bessere soziale Zustände in die Wege leiten; sie wollte die Arbeiterfürsorge fördern, namentlich die Sicherstellung der arbeitenden Klassenfür Zeiten der Arbeitslosigkeit, und wollte die betreffenden Klassen dazu erziehen helfen, aus eigenem Bedürfniß heraus ein menschenwürdigeres und hygienischeres Privatleben anzustreben. Um unparteiisch urtheilen zu können, um nicht auf die einseitigen Auskünfte des einen oder anderen Theiles angewiesen zu sein, nahm sie selbst die Stelle einer Arbeiterin an und richtete dabei ihr Augenmerk auf den Grad der Gefahren, die der Industriearbeiterin im Betriebe drohen und auf den Umfang der Haftpflicht des Arbeitgebers.

Sie meldete sich dann zur Arbeit im Bureau des „State Department of Labor“ und begleitete dort die Stelle einer Arbeits-Inspektorin (nebenbei gesagt, war es in Erledigung dieser Pflicht, daß sie den frühen Tod erlitt. Auf einer Fahrt verlor sie anscheinend die Kontrolle über die Maschine und der Kraftwagen stürzte einen Abhang hinunter). Letzten Winter studierte sie, um ihren Schützlingen besser helfen zu können, zwei orientalische Sprachen, wohl wissend, daß die Klasse von Arbeiterinnen, deren Wohl sie anstrebte, am leichtesten und vollkommensten dem vertrauen, der ihre Sprache spricht. Die Hauptsprachen beherrschte sie ohnehin.

Sie ist dahin gegangen, in der Blüthe ihrer Jahre, den Geist erfüllt von großen, weittragenden Plänen, das Herz zugeneigt denen, die sie emporzuheben gedachte zu einer menschenwürdigen Existenz, zu einer mehr intelligenten Bewerthung des Daseins, die eine erste Bedingung zum Menschenglück ist. Man braucht sich an der Bahre des Frl. Wörishoffer nicht erst auf den Spruch zu besinnen, daß man den Todten nur Gutes nachsage, es ist vielmehr eine Wahrheit, die sich jedem Menschen aufdrängen muß: hier ist ein großer Zukunftswert unterbrochen worden durch den erbarmungslosen Allbezwinger Tod! Wenn man das unentwegte Wirken der Todten beobachtet hat in den wenigen Jahren, seit sie von Bryn Mawr graduierte, da fühlt man, daß die Zukunft zu hohen Erwartungen berechtigen musste. Und daß nicht ich allein, trotz der eben betonten Pflicht der Pietät, in dieser Weise urtheile, beweist unseren Lesern der nachstehend zitierte Leitartikel aus einem unserer anglo-amerikanischen Blättern, der „Evening Post“ vom 12. September. Es ist überhaupt unmöglich, anders zu urtheilen. Und dieses Eingehen auf das Streben einer Frau der jüngeren Generation, ist eben eine weitere Pflicht, der in dieser Abteilung, wi eoben erwähnt, genügt werden muß.

Es heißt da also:

„Wenn man sagt, daß Staat und Stadt durch den Tod des Frl. Carola Wörishoffer bei einem Auto-Unfall einen schweren Verlust erlitten haben, mag das manchem der Leser als Übertreibung erscheinen. Die junge Dame war nur 25 Jahre alt, ihr Name in weiteren Kreisen nicht bekannt, und daß sie reich war, gab ihr, so interessant es auch sein mag, im Allgemeinen keine Ausnahmestellung in dieser Stadt des Reichthums. Und doch möchten wir obige Behauptung nicht um ein Jota modifizieren. Frl. Wörishoffer ererbte mit ihrem Vermögen eine seltene Erkenntnis öffentlicher Pflichten, die moralisch mit großen Mitteln verknüpft sind. Von ungewöhnlichen Fähigkeiten, widmete sie sich in früher Jugend dem Problem des arbeitenden Volkes, nicht lediglich durch theoretisches Studium, sondern indem sie thatsächlich sich unter sie Leute mischte und ihre Lasten mit ihnen trug. So war sie bereit und willens in Wäschereien zu arbeiten, um die Lage der Arbeiterinnen in diesen zu erkunden. Den reichen Nichtsthuern von Newport oder der Fünften Avenue würde ein solches Vorgehen zweifellos nicht nur einen plebejischen Beigeschmack verrathen, sondern direkt vulgär erscheinen. In der That muß frl. Wörishoffer ein Räthsel für sie alle gewesen sein. Sie, die es in ihrer Macht hatte, wenn sie wollte, in der Presse, die persönlichen Nachrichten kultiviert, in der Rolle einer Erbin und Schwester einer Gräfin an hervorragender Stelle zu erscheinen, Bälle und „Functions“ zu besuchen und ihre Loge in der Oper zu besitzen, zog in Wirklichkeit die bescheidene Thätigkeit einer staatlichen Arbeits-Inspektorin vor, und dieser ging sie nach, als der Unfall sich ereignete. Nach unserem Empfinden hatte Frl. Wörishoffer schon ausgezeichnete Dienste in dem Kreuzzuge der Humanität geleistet. Ihr leuchtendes Beispiel sollte viele andere bewegen, in ihre Fußstapfen zu treten“.

Soweit die „Evening Post“. – Ich knüpfe an die Schlussworte des Artikels an, indem ich der Überzeugung Ausdruck verleihr, daß das so früh abgeschlossene Wirken der Dahingeschiedenen wohl kaum ganz umsonst gewesen ist. Der Same ist gesäet und die Saat ist aufgegangen, wenn auch nicht zur Reife gelangt. Es werden, durch ein derart erhabenes Beispiel aufgerüttelt, sich hoffentlich Andere finden, die die Arbeit da aufnehmen, wo die im Tod erstarrenden Hände sie sinken lassen mußten. Es werden sich Andere finden, die ihrem Vorbild folgend, den Besitz unter dem Goethe’schen Gesichtspunkte betrachten: „ Was Du ererbt von Deinen Vätern hast, erwirb’ es, um es zu besitzen“. An dieser Bahre muß auch der rabiateste „Feind der Besitzenden“ ehrfurchtsvoll sein Haupt entblößen. Die Dahingeschiedene hat es verstanden, wie ihre älteren Familienmitglieder, Unzufriedenen die Waffe zu entwinden und ihnen zu beweisen, daß reiche Mittel nicht jedes Herz verhärten.

Sie hat diesen Mitteln für sich selbst nicht mehr entnommen, als den einfachsten Lebensbedarf, aber die Oeffentlichkeit wird nie erfahren, was sie im Stillen Guthes gethan hat. Sie hatte ein Recht auf den Lebensgenuß der Jugend und des Reichthums, sie hat ihm entsagt um ihrer ärmeren Schwestern willen. Ganz verloren kann ein solches Beispiel und ein solches Wirken niemals sein. Die Früchte werden reifen, und wenn es eine Gerechtigkeit in der Welt gibt, dann wird der Name Carola Wörishoffer in den Reihen derer fortleben, die Gutes und Edles zu schätzen wissen, und namentlich in den Reihen derer, denen diese Früchte zugute kommen.

(...) und kindlichen Uebermuthes. Dieses kräftige, überschäumende Naturell, verbunden mit den äußeren Verhältnissen, ließ vermuthen, daß sie dereinst das Leben so recht froh und aus dem Vollen genießen werde. Nie hätte ich es für möglich gehalten, daß sie sich in so ernster Wiese den Weg der Pflicht bahnen würde. Die letzten 10-11 Jahre haben der Familie schwere Schicksalsschläge zugefügt, eins um das andere sah die Mutter der nun Verstorbenen ihre Lieben um sich herum dahin gehen; vor mehreren Jahren sank die älteste Tochter, Gräfin Seilern ins Grab, ungefähr im gleichen Alter als jetzt die Schwester, da wurde es stiller und stiller um die schwer geprüfte Frau. Diese jüngste Tochter war alles was ihr geblieben, nun ist auch sie dahin. Nur jenseits des Oceans leben noch zwei Schwestern von Frau Wörishoffer.

Ich habe mich kaum je so bis ins Innerste erschüttert gefühlt, so geradezu erbittert, bei einem Schlage, der Andere getroffen, als in diesem Falle. Wer das leben der Dame kennt, so still, so ernst, so gänzlich dem Wohle der leidenden Menschheit gewidmet, nichts für sich begehrend, das Herz und Gemüth offen für fremde Leiden, der muß sich sagen: hier ist eine himmelschreiende Ungerechtigkeit, dieser letzte, entsetzliche Schlag hätte dieser edlen, ohnehin so einsamen Frau erspart bleiben müssen! Vor einem Jahre, als ich selbst Schweres erlitten, da hatte sie von Europa aus schriftlich, nach ihrer Rückkehr persönlich alles Liebe und Gute auf mich gehäuft, denn „ich weiß wie es thut“ meinte sie. Und nun, was soll man sagen und thun, um sie zu trösten, die ihr Letztes, Liebstes hergeben musste, unter so entsetzlichen Umständen (die Mutter weilte bei Eintritt der Katastrophe noch zum Besuche der Schwestern in Europa. Die Tochter wollte hier ihre Pflichten nicht verlassen). Was soll man thun, um zu trösten, trozdem man „weiß wie es thut?“

Da kann man, nachdem man eigenes Schicksal gefasst getragen, nicht umhin, anzuklagen! Wohlzuthun und mitzutheilen in dem fürstlichen maße, wie sie es thut, nach allen Richtungen hin, schafft wohl innere Befriedigung, aber ganz und allein kann es ein Menschenleben denn doch nicht erfüllen, ein bischen Glück, ein einziges, muß der Mensch für sich behalten dürfen.

Briefkasten der Frau Anna

Adresse: „Frau Anna“, „N.Y. SAATS-ZEITUNG, P.O.B 1207 New York City.

Carola Woerishoffer by William Mailly - September 24, 1911

New York Call, New York City, September 24, 1911

Something more than a mere obituary notice is due from the press, at least, the memory of Miss Carola Woerishoffer, who died on September 11 from injuries received in an automobile accident near Binghamton. It is not often that. an unqualified tribute can be rendered, without reservation, to one who belonged by right of birth, station and material possessions to another class, but who allied herself with the organized working class movement in a sincere, whole-hearted desire to advance that movement and improve by positive, constructive methods, the social conditions of the workers, and of the working women especially. But this is one instance when such a tribute can well be written, the one question being as to the manner in which it shall be written, without seeming exaggeration, and yet to do simple justice to an exceptional character.

Miss Woerishoffer was exceptional in that she came to the working class movement not to teach but to learn, not to direct but to serve, not to command but to obey. She aspired to be, and she was, simply a common soldier in the army of the militant workers. And so well did she live her part that among the host of working women with whom she mingled throughout her various activities few knew her for other than what she appeared to be. She tried, not only to work with and for them, she tried to be one of them, to feel as they did, to see things as they did, so as to better equip herself in the attempt to remedy the conditions from which they suffered.

That was the spirit in which, four years ago, she began her work, and she never lost that spirit. If anything, she became more and more possessed of it. From the beginning she was averse to notoriety or publicity and this aversion became more marked with her as she went on. This was not a morbid shrinking from public notice. It was merely an instinctive distaste to have exhibited as something extraordinary What was with her natural and spontaneous. She was neither supersensitive, hysterical nor self-conscious. She took joy in what she did, a. healthy, youthful , invigorating joy, for she felt that she was doing something that might be of some fine, joyous use in the world. So her name very seldom appeared in the public prints and she was practically unknown personally outside of an intimate few.

Of her actual activities, it would be impossible to make a record. It is impossible even to suggest them, for the simple reason that they would appear so improbable as to invite skepticism. Her innate passion for adventure led her into strange ways and places, and no one but herself was ever to know what she undertook in order to learn the actual facts of working class life. But what ever she did she did without ostentation -- noiselessly, vigilantly and thoroughly.

For instance, during one entire summer, that of 1909, from June to October, when those who could afford it were gladly leaving the heated city, she remained behind and worked in laundries so as to acquire information for use by the Consumers' League. She went from laundry to laundry staying long enough in each place to learn what she wanted, working for the same wages as other women and at all kinds of labor, unsuspected by employers and workers alike, doing from choice what other women were compelled to do from necessity. Only in one place was she suspected of not being a regular working woman. There a girl walked up to her one day and asked her: "What are you doing here? You don't talk like one of us." Later, Miss Woerishoffer presented the information thus collected before the Wainwright Commission on Workmen's Compensation, on behalf of the workers in laundries, and to show the hazardous character of their employment.

She was fortunate in the possession of a remarkable physical constitution, and this enabled her to undergo hardships and to invite experiences that would have daunted a person of ordinary physique. She had never been ill a day in her life, she had an infinite capacity for labor, and she was oblivious to the ordinary demands for rest and sleep. Her physical endurance was practically unlimited, and she gave of it relentlessly and yet without recklessness. She had learned to conserve her strength, and there was deliberation in all that she did. She came through her Bummer's work in the laundries as fresh and vigorous as when she started. She enjoyed it, she said.

Not many people knew outside of her immediate circle that she was one of the mainsprings of the Women's Trade Union League in the great shirtwaist strike winter before last. Even the girl strikers themselves hardly knew. But she was at work all the time, giving of her energy and time as freely and as quietly as she gave her money whenever and wherever it was most needed.

As I have already said, she never assumed to give orders, but to receive them. At the commencement of the strike, she was deputized to attend the Police Court and look after the girl pickets who were being arrested and brought there. A more disagreeable place for one of any sensitiveness to degradation and suffering could not very well be selected, but she never hesitated. She went there and stayed every day right through the strike, taking care of the girls, directing them where to go and what to, going their bail and saving them from innumerable impositions and hardships. And at the end of the strike she declared she thought she had had the best job of anyone.

One incident that occurred during that strike was characteristic of her. For a while the magistrates accepted cash bail for arrested pickets, but later refused to recognize anything but real estate. Miss Woerishoffer was surprised one night when this decision was put into effect. It happened that none of her money was invested in real estate, but the next night she turned up with the deed for a piece of property for which she had negotiated during the intervening twenty-four hours and thereafter the magistrates had no excuse for rejecting her on any striker's bail.

She continued to act as bondsman for the Ladies' Waist Makers’ Union when the strike was over. During my service as manager of the union last winter we had occasion to call upon her frequently to go to the Night Court and bailout some striking union member. And she never failed to appear, no matter at what hour we notified her she was wanted. Her instructions were that she would come) regardless of the hour, and it was not unusual, both during the strike and after, for her to get out of bed at a late hour in answer to a summons. There was no grumbling about it. She never questioned the necessity or the wisdom of a summons or of an order from any responsible official with whom she worked. She was always "on the job."

I think that phrase expresses it as well as anything could.

She was always "on the job." As another instance: The morning after the Triangle Waist Company disaster, she was one of those who went out as visitors to the homes of the victims to procure information for relief. She was at work all day and into the night.

That day the union decided to open its relief fund. The call was drawn up, and for public effect several members of the Women's Trade Union League were sent out to obtain indorsements to the call from prominent people. I was entrusted with its issuance to the daily papers. Reports of indorsements were made to me at the Rand School. At the last moment almost it was thought that the first public announcement of the fund should be headed by a substantial sum from some organization or individual. The union office was closed and nothing could be done there.

Then some one suggested, "Call up Miss Woerishoffer." "What, at this hour?" I said -- it was nearing midnight. "That makes no difference. She won't mind -- call her up."

I did so. A maid answered. Miss Woerishoffer had retired.

"Never mind, then," I said. "Wait a moment," said the maid, "what do you want with her?" I explained. Oh, that's different," declared the maid , "wait a moment."

Shortly Miss Woerishoffer came to the telephone. It was too late, she said, to do anything tonight, of course, but she would be at the office in the morning.

Next morning when I reached the office she was there waiting for me. I thought I was early, but she was earlier. She arose as I came in, and as we shook hands she put a roll of bills into mine. "That's the best I could do this morning." she said, "please don't give my name -- just say, collected by C. W. if anything." Before I could ·reply she was gone. The roll contained $505.

A newspaper, in a report of her death, stated that she appeared once at the Legislature "fashionably attired." Nothing could be farther from the truth. This was an invention of an imaginative reporter. She always dressed simply and neatly with clothes of a quiet, dark material. In this she was as unostentatious as in all her actions. She was the last person in the world to at tract attention to herself, and she had the rare faculty of doing unusual things without pretension or affectation. Of no one could it ever be more truthfully said that she was absolutely devoid of self-seeking or desire for personal glory.

She was wealthy, and she used her wealth as it is seldom used, even by those of braver pretensions. She gave unsparingly to projects that she considered of positive social value. She was not a philanthropist. She abhorred philanthropy as it is commonly practiced. She was interested in constructive social work as a means to an end, not as an end in itself. If she assisted individuals it was indirectly and in a way that evaded charity and relieved the individual from being an actual recipient of charity. How much she gave to organizations will probably never be known. From the time she joined the Women's Trade Union League, three years ago, she was of decided financial aid in the important work of organizing the working women of New York. She asked nothing in return but the opportunity of doing whatever the officials wanted her to do, and they soon found that the merest drudgery was welcome to her, and she deemed it a privilege to do it.

In every respect, then, this young woman, for she was only 26 years old when she died, was unique, stereotyped as the word may appear. She not only, by force of will and firm determination, dissociated herself from her own class and put from her all that association with that class means to young and weal thy women) but in doing so she undertook to do a valuable concrete work in the world under circumstances in which she found increasing satisfaction and ever impelling enthusiasm. There was no benign condescension about it, no assumption of superiority, no striving for brief and ephemeral press notoriety and superficial public adulation. The very simplicity and sincerity of her character precluded all thought of

that. She had her work to do and she did it. And she was the 1ast one to have it thought she was doing anything that anyone else could not do with the same opportunities she had.

She met her death while making a tour of the railroad labor camps of New York state, a work which had taken the entire summer and for which she had had herself appointed a special investigator for the Bureau of Immigration of the state Department of Labor. That she should, in her last words, have expressed regret that she could not live to do all that ~he had planned as "there was so much to be done," was a revelation in itself of her devotion to and concentration upon a life of usefulness to humanity. She had only begun her work and the possibilities for usefulness were inestimable.

She did not deserve to die so soon -- the working women's movement did not deserve to lose her. That such as she should meet such a fate at such a time comes in fresh confirmation of how inexplicable life is.

E.C. Woerishoffer, Bryn Mawr - October 26, 1911

Book: Carola Woerishoffer Her Life and Work - 1912

[Tarbell, Ida] Bryn Mawr College Class of 1907.

Carola Woerishoffer Her Life and Work. [Bryn Mawr, PAl: Bryn Mawr College, 1912. $125.00

First Edition. 8vo; 137pp; original blue gilt-stamped cloth with title on front panel and spine, spine and tips a bit rubbed, ink ownership inscription on front pastedown, else very good.

Carola Woerishoffer (1885-1911) social work and philanthropist was born to a wealthy New York family. From her father who died the year after her birth, she inherited well over a million dollars. She attended Bryn Mawr determined to pursue a career in social work. Immediately upon graduation she joined the board of managers of Greenwich House, a neighborhood settlement founded by Mary Simkhovitch.

Preferring that her good works remain anonymous, she worked for four months, fifteen hours a day, as a laundress in a dozen different establishments observing the deplorable conditions reporting them to the Consumer's League of New York City. She joined the New York Women's Trade Union League and backed the 1909 strike by putting up her own property for a $75,000 bond, declaring she would remain in court until the strike was settled.

In 1911, while serving as an investigator for the State Bureau of Immigration, she worked on the Triangle Fire Investigation and did much work collecting evidence for the surviving workers. She also managed to find time to serve as a district leader of the New York Woman Suffrage Party.

She was killed in a car accident at the age of 26 - cutting short a promising career of public service. She left $750,000 to Bryn Mawr which was used to found the Carola Woerishoffer Graduate Department of Social Economy and Social Research, the first professional school of its kind to be connected with a college or university.

Ida Tarbell contributed the 32-page Introduction to this memorial volume, which was later published in the "American Magazine," July 1912. In the Introduction Tarbell eulogizes her subject calling her actions part of the "Revolt of the Young Rich." The balance of the text is a series of vignettes from professors and staff who knew her. According to NAW, this text is the primary source of information for this extraordinary woman. NAW III, pp. 639-640

(9336)

The Carola Woerishoffer Graduate Department of Social Economy and Social Research - 1915

Carola Woerishoffer - American National Biography - 1999