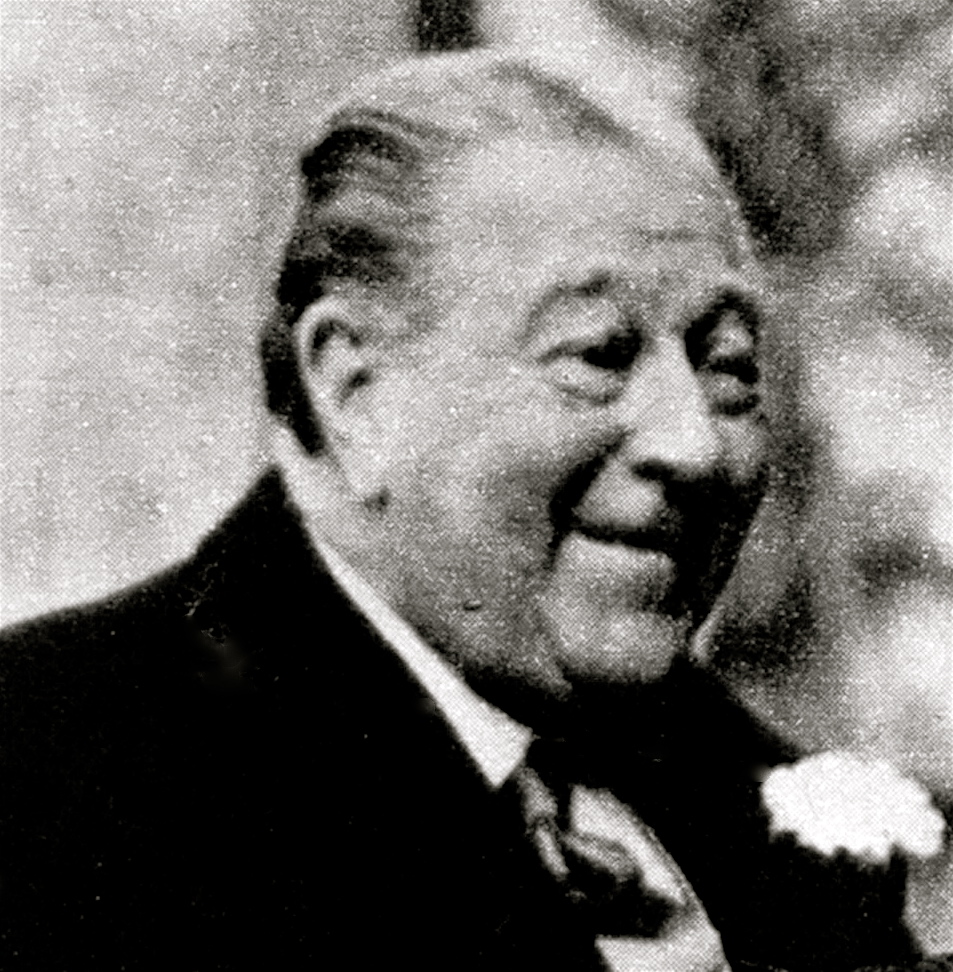

Antoine Seilern

A complete and accurate description of Uncle Antoine's life and work can be found under:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antoine_Seilern

The Princes Gate Collection

Foreword

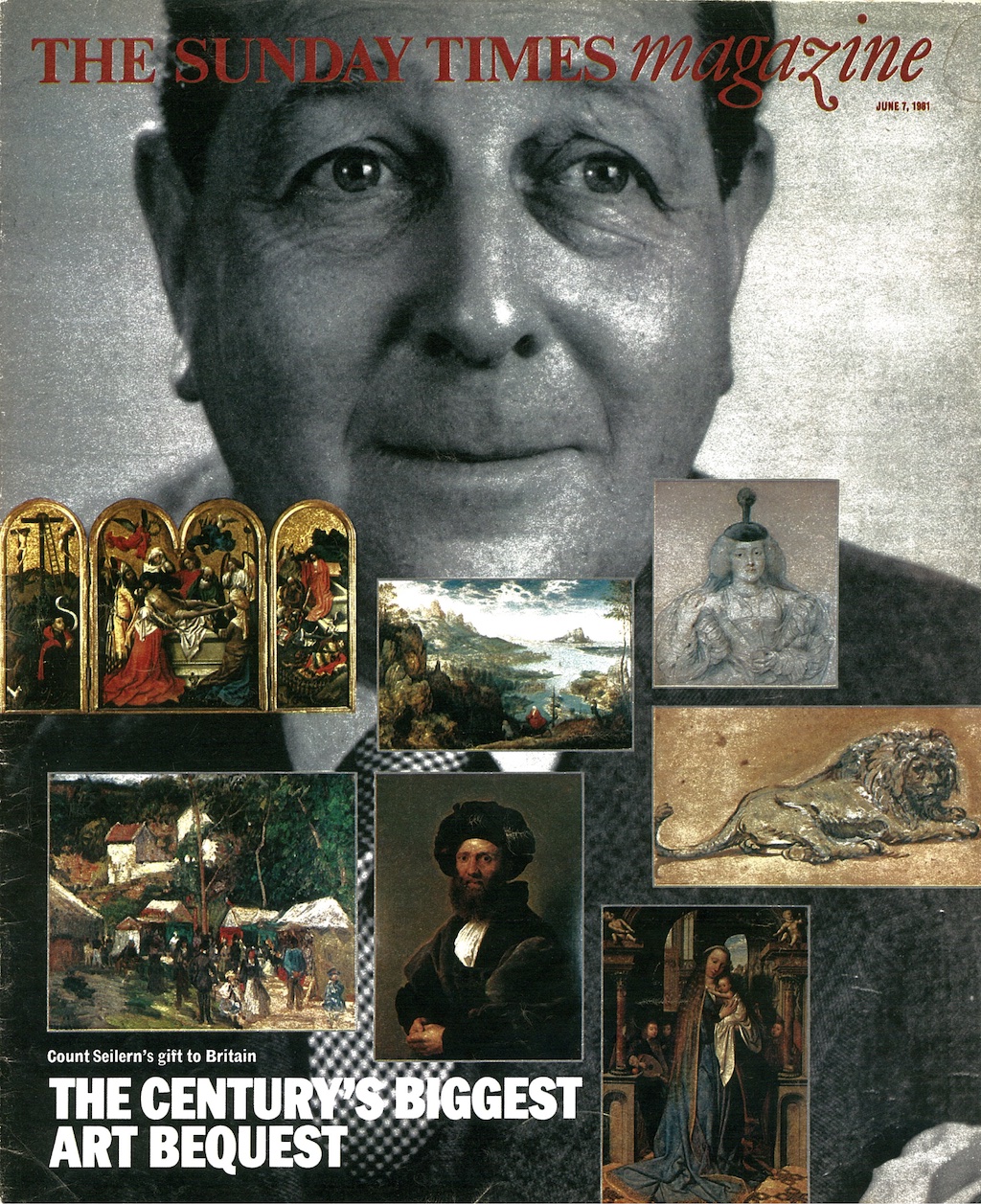

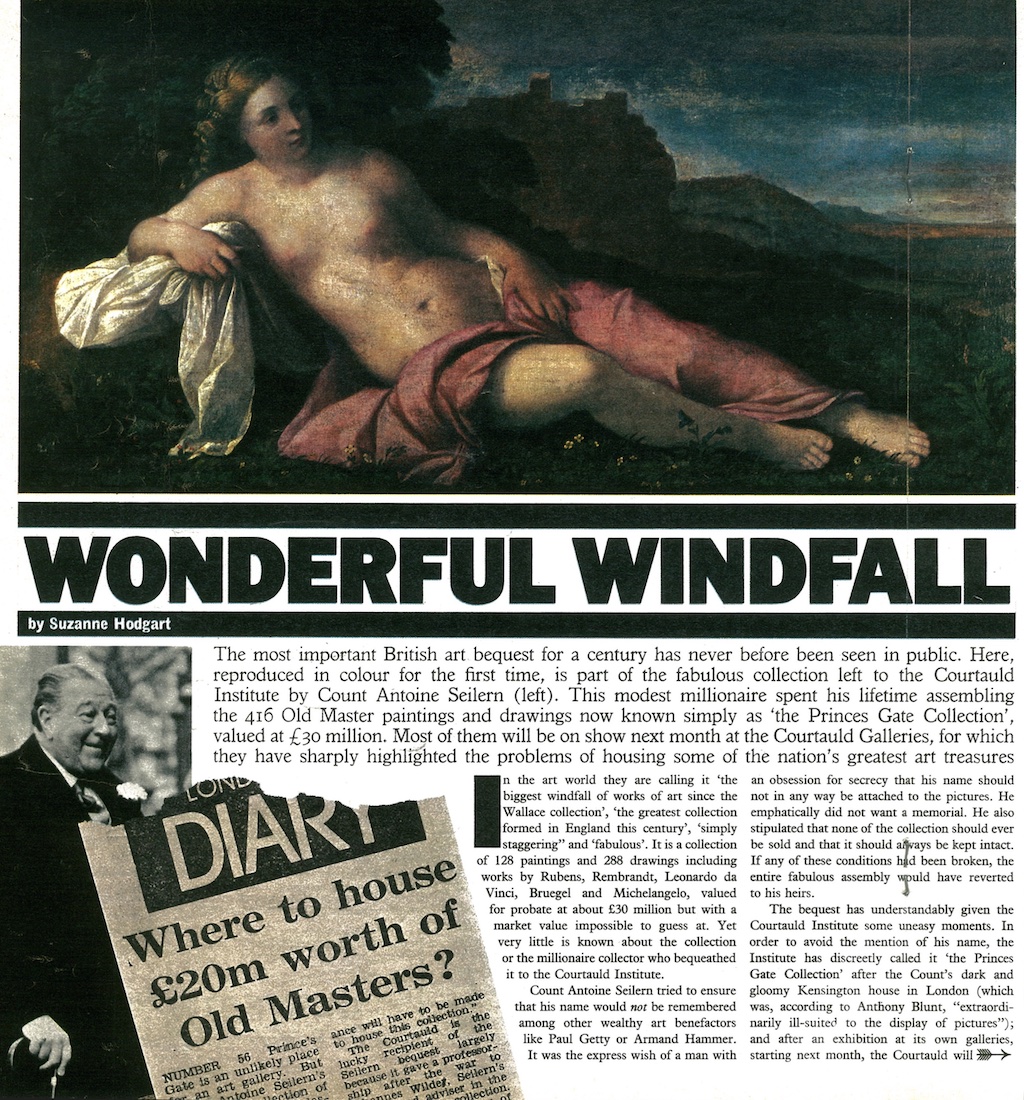

When this exhibition opens to the public on 17 July at the Courtauld Institute Galleries it will be the first time that the Princes Gate Collection, formed by Count Antoine Seilern, has been exhibited in a public gallery. Individual paintings and drawings were lent to exhibitions by Count Seilern in his lifetime, and the collection was always made accessible to scholars and students. We hope and believe that visitors to the exhibition will be thrilled by the range and quality of the paintings and drawings on show, and that they will derive great pleasure and inspiration from them. For Count Seilern wished others to share the life-enhancing experience that he himself derived from the study of great masterpieces.

The Collection has been bequeathed to the Home House Society Trustees, the Trust that was set up in 1931 by Samuel Courtauld when he endowed the Courtauld Institute of Art and gave to the University of London the magnificent foundation collection which bears his name. The Courtauld Institute of Art, in particular, and the University of London of which it is a part, have been no less fortunate in their benefactors in the fine arts than in other fields. Although the bequest took effect in July 1978, it was not possible to exhibit the Princes Gate Collection until certain legal formalities had been completed. It was also necessary to find additional space to house temporarily those parts of the Courtauld Institute's collections, now so splendidly augmented, which have to be stored until some larger, permanent home could be found. The Home House Trustees and our Committee of Management felt that it would be most appropriate to show the Courtauld Collection and the Princes Gate Collection together at the Woburn Square Galleries for about a year, since it would not be possible, sadly, to continue to show the Gambier-Parry, Lee of Fareham, and Fry Collections in the restricted space available to us there. (Only the Lee of Fareham Rubens Descent from the Cross has been included, since it relates to Rubens' Visitation and Presentation in the Princes Gate Collection.) This underlines our need for more exhibition space where almost all the treasures in our collections can be publicly displayed. It is to be hoped that negotiations between the University and the Government, and the consultants' studies already initiated, will be successfully concluded and enable us to move the collections and, ultimately, the Courtauld Institute, to the Fine Rooms at Somerset House, thus re-uniting under one roof our teaching activities with the art collections.

The present exhibition contains all but a few of the paintings from Count Seilern's collection, and a selection of some sixty of the finest of the drawings. There will be two selections (A and B) of about thirty drawings each. They will each be shown for approximately six months at a time and both sections A and B are included in this catalogue.

An enterprise of this kind cannot be undertaken without financial help, and we wish to record our deep gratitude to National Westminster Bank for generously agreeing to sponsor this exhibition. We would also like to thank most warmly the Rt. Hon. Paul Channon, P.C., M.P., Minister for the Arts, for agreeing to a government indemnity for this exhibition.

The catalogue has been compiled by Mrs. Helen Braham, who assisted Count Seilern in cataloguing and curating his collection. The catalogue contains new information and references to books and articles published after the Princes Gate Collection catalogues appeared between 1955 and 1971. We thank her for undertaking the work of preparing this exhibition catalogue and for meeting cheerfully the exigent deadline set her. All exhibition catalogues are in the nature of progress reports, and this one is no exception. Mrs. Braham joins with us in thanking those of our colleagues who read entries for works which fell within their specialist fields and. who made helpful contributions.

We wish to thank our colleagues at Senate House and in the technical services departments of the University, including our own Department of Technology and Conservation, our Photographic Department, Mr. William Bradford and Mr. William Clarke, without whose help this exhibition could not have been realised. Finally, we thank Mr. Gordon H. Roberton of A. C. Cooper Ltd and Mr. Graham Johnson and Mr. Tony Sumner of Lund Humphries for their essential help in the design and printing of this catalogue.

Peter Lasko Denis Farr

Director Director

Courtauld Institute of Art Courtauld Institute Galleries

Introduction

The collection bequeathed by Count Antoine Seilern, at his death on 6 July 1978, to the Home House Trustees for the Courtauld Institute of Art, London University, is the fruitful result of nearly half a century of scholarship and acquisition. It comprises chiefly paintings and drawings, but also prints and a large art library, including rare books. Also forming a part until 1978, when they were bequeathed to various other private and public collections, were illuminated manuscripts, sculpture, coins and medals, Greek and Chinese antiquities (recently on loan to the British Museum), a further collection of prints, notably by Durer, a few other paintings and a group of drawings chiefly of the 19thcentury Austrian and German schools.

Outstanding among this wide-ranging assembly of works of art are the paintings and drawings which now form part of the Courtauld Collections. They span a period of over 600 years, from 1338 (Bernardo Daddi's Triptych, 14[1]) to 1950 (Kokoschka's Triptych, inv. no. 260 - not on exhibition on account of its size) and include works of most of the major European schools. The work of one particular artist, however, receives pronounced emphasis: Rubens is represented by twenty-three drawings and thirty-two paintings. By only one other artist is there a remotely comparable number of works: Giambattista Tiepolo's twelve paintings and over thirty drawings. All but one of these paintings are modelli, or oil sketches, as are at least twenty of Rubens' paintings.

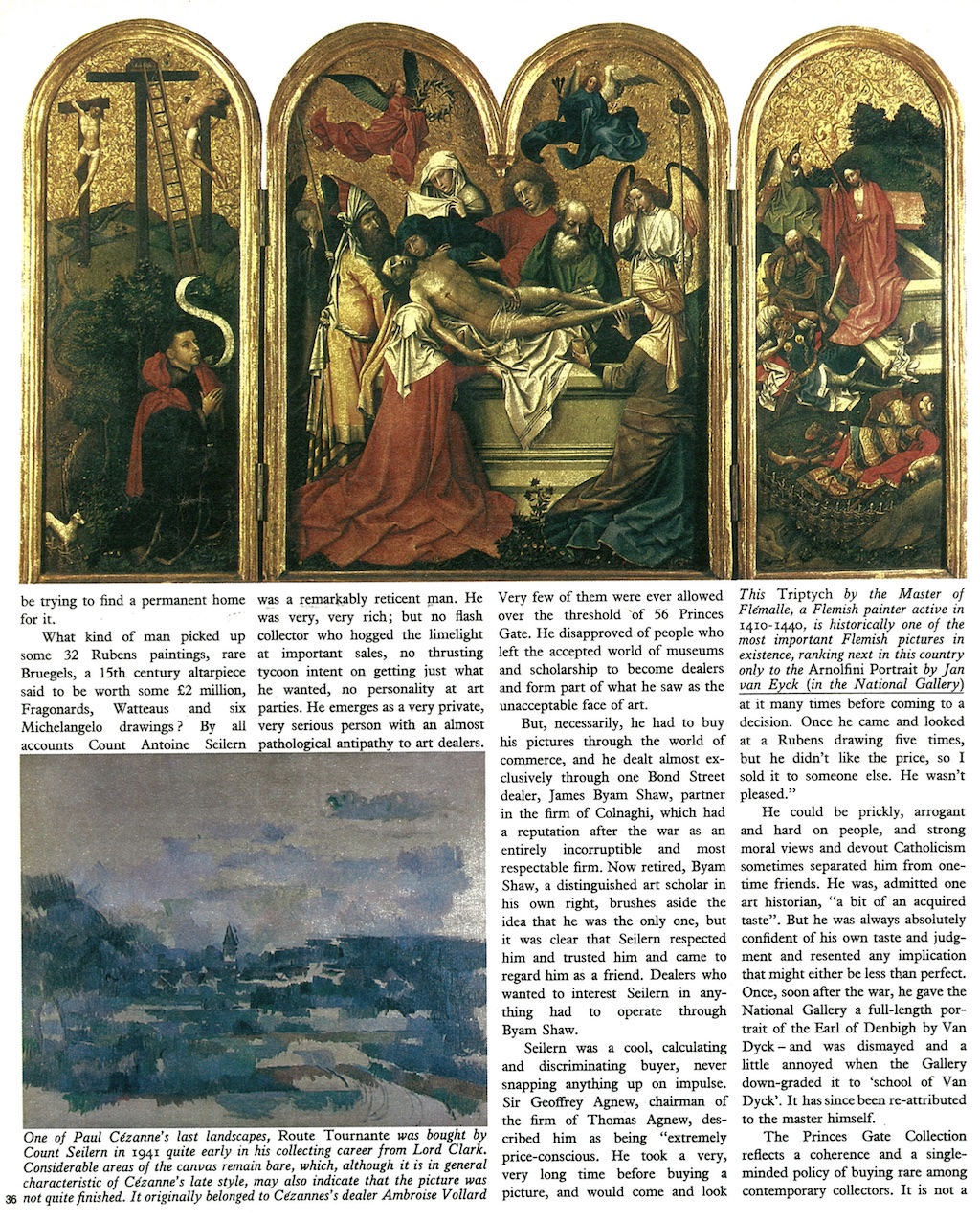

The Flemish and Italian paintings and drawings are, indeed, by far the most numerous, each beginning with an important and particularly well-preserved triptych: the earliest known masterpiece of Netherlandish panel painting, by the Master of Flemalle (45) and Bernardo Daddi's altarpiece of 1338. Other early Flemish works include a drawing by Hugo van der Goes (167), a group of drawings (126-8, 155-6), notably landscapes, and two paintings (8, 9) by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, whose pictures are rare outside Vienna, and Quinten Massys' outstandingly well-preserved Madonna (44). From the 1 7th century - and apart from Rubens - there are chiefly works by Rubens' pupil, van Dyck, and by David Teniers the Younger, whose association with the collection of the Austrian Archduke Leopold Wilhelm made him of particular interest to Count Seilern: there are fourteen of his small copies (91-104) after paintings in the Archduke's collection, made for the production of his engraved catalogue, the first of its kind. Count Seilern's early attachment to the Kunsthistorisches Museum and his admiration for Archduke Leopold Wilhelm as the founder of its collections, led him to bequeath to Vienna two paintings (by van Dyck and Fetti, inv. nos.45 and 106) which had strayed long ago from the archducal holdings.

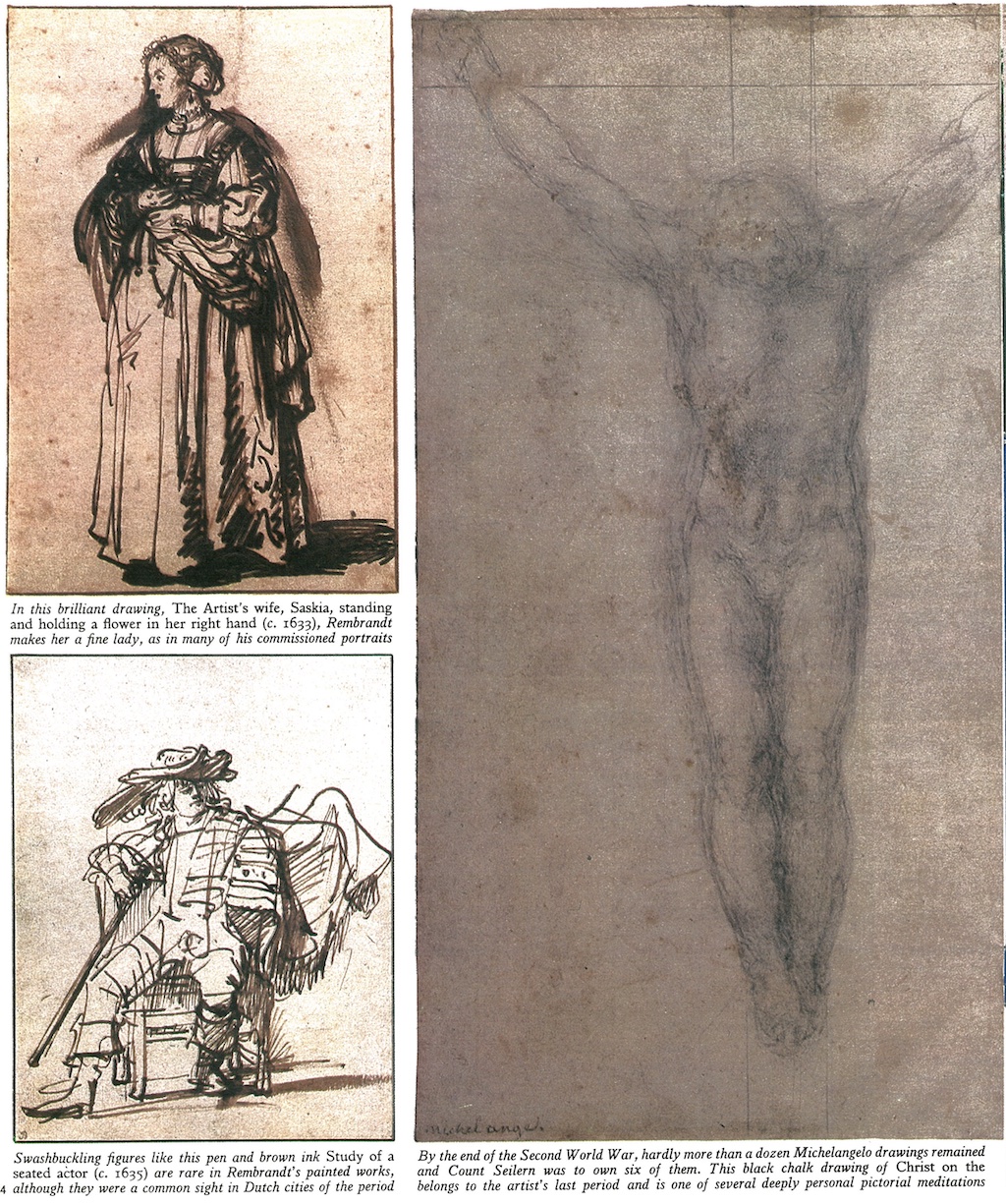

Of the Italian schools it is, with a few exceptions, notably the triptych of 1338, the 16th and 18th centuries which provide the two focal centres - and within these the Venetians in particular. In the 18th century Giambattista Tiepolo dominates; he is accompanied by, among others, his son Domenico (drawings), Guardi (a painting, 30, and fourteen drawings, 136), Sebastiano Ricci (57), Pittoni (52, 53) and Canaletto (two important drawings 129, 130). The 16th-century Venetians include Titian (121), Tintoretto four paintings, (117-120, and five drawings, 152), Palma Vecchio (48), Paris Bordone (6) and Lotto (an attributed drawing, 137, and three paintings, 37, 38, and one not on exhibition). Artists from other North Italian centres include Parmigianino (some twenty drawings, 140, 173-4, and two of his rare paintings, 49, 50). The Italian drawings of the period are by a wide range of artists, from many lesser-known ones to the greatest - Bellini (125), Mantegna (170), Leonardo (169) and no fewer than six sheets by Michelangelo (138-9, 171-2).

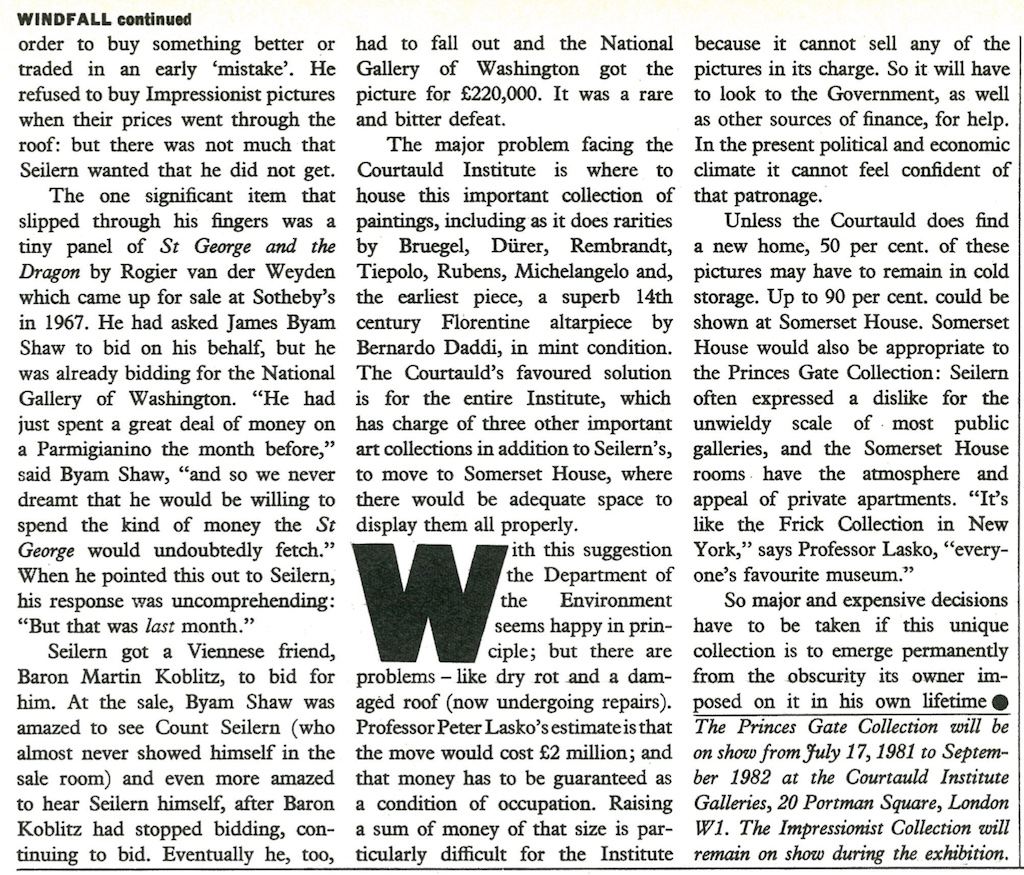

No English works of art are to be found here (a few drawings by Count Seilern's cousin, Lord Methuen, were formerly in thecollection); only one minor Spanish painting (not on exhibition) and a Goya drawing; of the Germans only two small paintings (1, 33), but three drawings by Durer (161-3). There is only one Dutch painting (32), but Rembrandt is represented by thirty drawings (142-5, 177-8). The French collection is larger and more varied, from Claude (one small painting, 1 1, and half a dozen drawings, 134, 158), through the 18th century - drawings, mainly by Watteau (nine; 153) but including also two Fragonards (135, 166) - to the 1gth-century Barbizon painters, Diaz (18) and Daubigny (15), and the Impressionists: paintings by Pissarro (51), Manet (40), Berthe Morisot (46), Renoir (56), Degas (16, 17) and ending with Cezanne's late landscape (10). Drawings of the period include three by Cezanne (132-3, 157).

The 2oth-century works are almost all Austrian and by personal friends of Count Seilern's, notably Oskar Kokoschka. His large Triptych was executed in 1950 as a ceiling painting for 56 Princes Gate and was painted on the premises. These, and the many (uncatalogued) 1gth-century Austrian drawings no longer with the collection, are evidence of Count Seilern's special affection for the art and culture of that country.

The breadth of the collection reflects a considerable catholicity of taste, but there is also a discernible pattern to its formation. The high quality and good condition of the majority of the works of art of all types are evidence of Count Seilern's connoisseurship; where quality or condition is relatively poor the reason may be either that it was acquired when he was still a novice, or it was bought as an act of kindness or charity, or because it was of historical interest. It is a collection of outstanding taste and the product of a love of fine works of art for their own sake. It is also a scholarly collection par excellence, and much of its interest derives from the relationship of works brought together here, often for the first time since the artist's death.

In the Rubens collection Count Seilern assembled three related Conversions of S. Paul- two paintings (68, 69) and a drawing (180), the latter having been acquired in two parts from different sources. Similarly, six oil sketches or modelli (72-77) are brought together here which were for Rubens' great series of ceiling paintings in the Jesuit church in Antwerp; there is also a set of 18th-century watercolour copies and a book of engravings recording this now lost series. Other interesting documents relating to Rubens include the MS. Inventory of his collection made at his death for the perusal of Charles I, the artist's last surviving autograph letter, and the transcript of a lost 'Pocketbook' of his sketches and notes ('MS. Johnson'). Another project at the heart of the collection is Tiepolo's last major commission, the altarpieces for Aranjuez in Spain, of which the five modelli (111-115), a drawing (184) and the fragment of an altarpiece (1 16) were assembled over the years.

It is worth remarking on the number of copies after the work of other artists, apart from the fourteen copies by Teniers: four of Rubens' paintings (58, 62, 78, 80) and a drawing are copies, or near copies - after Titian, Raphael, Elsheimer, Pordenone; the van Dyck bequeathed to the Kunsthistorisches Museum is after Titian. There are Delacroix and Watteau drawings after Rubens, a modern 'fantasy' by Frankl also after Rubens, drawings by the same artist of medieval sculpture and studies by Tintoretto after Michelangelo sculpture (152). A copy attributed to Hans von Aachen is after a Barocci altarpiece and Steenwyck's small copper is after an engraving by Theodor de Bry; there are studies after Italian masters attributed to Jordaens and others by 18th-century French draughts men.

The history of the collection began in the late 1920s, when the first few paintings and drawings were acquired. Count Seilern came relatively late in life to the study and collecting of works of art. Born in Frensham, Surrey, on 17 September 1901, he was the third son of the Austrian Count Carl Seilern und Aspang (1866-1940; he also had British nationality) and his American-born first wife, Antoinette Woerishoffer (1875-1901). His mother died at his birth. His father's second wife, Countess Ilse, was held in the greatest affection by her stepson. Among his Seilern ancestors were two Austrian Court Chancellors, the first of whom, Johann Friedrich (1645-1 715), celebrated diplomatist and founder in 1684 of the titles of Seilern and Aspang, was the architect of the 'Pragmatic Sanctions', which ensured the succession of Maria Theresa and shaped the future course of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. His nephew and adopted heir, Johann Friedrich II (1676-1751), became Maria Theresa's Chancellor; one of his sons, Christian August (1717-1801) was ambassador to England.

Count Seilern's mother's family was of German origin, some three generations back, and had made its mark on New York-German society. Wealth, derived from their successful and politically influential German-language New York newspaper, the liberal New Yorker Staats-Zeitung, had been munificently spent, though without display, on philanthropic charitable concerns and foundations. Three generations of remarkable and distinguished women included the youngest, Carola, sister to Antoinette, highly intelligent and well-educated, who died in 191 1 at the age of 26, having spent her short adult life in dedicated social work. Carola and Antoinette's grandmother, Anna Uhl (nee Behr), later Ottendorfer (1815-1884), had, with the aid of her second husband, built up both the family's fortune and, likewise, numerous large-scale but modestly performed charities. Her daughter, Anna Woerishoffer (1850-1931), was Count Antoine Seilern's greatly loved and admired grandmother, with whom he spent some of his childhood in New York and Vienna. She, also, was a woman of great character, and held advanced views on social reform. She possessed a small collection of 1gth-century paintings which were inherited in 1931 by her three grandsons. These are now largely dispersed, except for the Diaz (18) and Daubigny (15) in this collection, which are the only works inherited by Count Seilern; the rest were all purchased, with the exception of one or two gifts from friends.

Count Seilern dedicated the first of the seven volumes of his catalogue of the paintings and drawings to Anna Woerishoffer, and he wished this collection to be associated with her name. From her family, which Count Seilern recollected with pleasure, his characteristically reticent generosity surely derived.

Count Seilern shunned publicity and to a remarkable degree wished to dissociate his name from his many acts of generosity to art institutions and charities. These should not now remain unrecorded; least of all can those who have always associated him with the present collection forget that the bequest was his. Other gifts included a van Dyck portrait to the National Gallery at the end of the war and two panels by Michael Pacher to the Vienna collections in 1939 (now Oesterreichische Galerie). Numerous institutions received financial aid, including the National Art-Collections Fund and the National Trust, which jointly received the proceeds from the sale of his catalogue. Most magnificent was his anonymous gift in 1946 to the British Museum Print Room - to which he showed many other acts of generosity - of about 1,250 Old Master drawings, almost the entire Fenwick Collection, with the exception only of a few which he retained.

He did not wish to be seen as a public benefactor, but as the owner of what he always termed his 'little collection'. He deplored most of all the use of art as financial investment, and the correspondingly huge sums for which works of art now change hands; he also mourned the decline of the true private collection, and the monolithic scale of institutions which could, in his view, detract from the enjoyment of art, but he supported generously the museums he befriended.

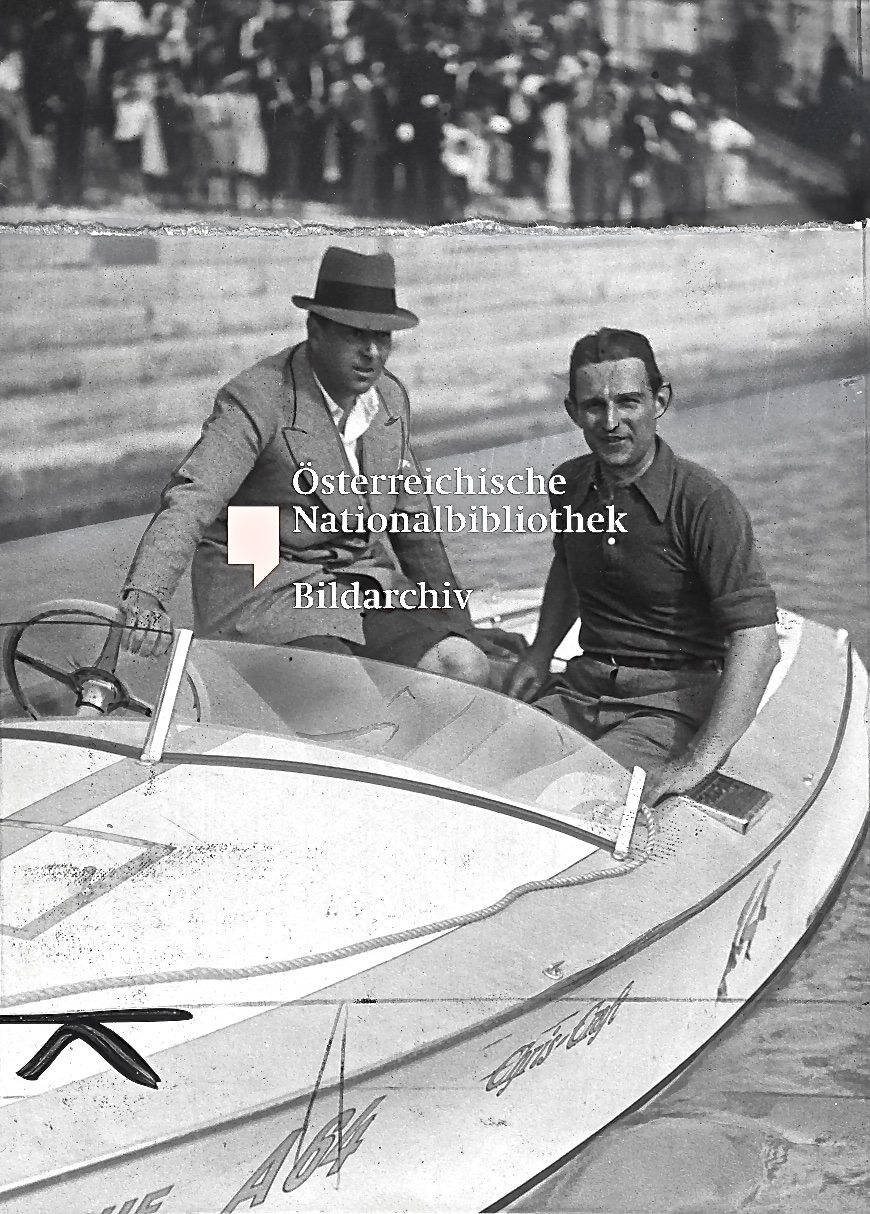

His youth as a sportsman was revealed at Princes Gate by the numerous big game trophies which adorned the stairwell. In the 1920s and early 1930s Count Seilern travelled widely and adventurously in search of big game: to Africa (1926 and 1930), Mongolia (1930), Indochina (1931), Yukon (1932-3); he made a round-the-world voyage (1930-1); he qualified as a pilot; he bred and raced horses with enthusiasm and success, until the war. There were also brief ventures into training in forestry, engineering, business and banking, but the course of his career changed when he enrolled in 1933 at Vienna University. He studied, until 1937, philosophy, psychology (with the Freudian, Buhler), history, archaeology and, principally, art history (with Swoboda, Sedlmayr, Schlosser). It was then that he came under the benign and learned influence of Johannes Wilde, who was on the staff of the Kunsthistorisches Museum. His friendship with Wilde (who died in 1970) was of paramount importance to him throughout the remainder of his life, and indeed led, through Wilde's post-war Deputy Directorship of the Courtauld Institute of Art, to Count Seilern's friendship with this Institute and ultimately to the present bequest. After some years spent in the pursuit of pleasures typical of the time and his social milieu, Count Seilern became, gradually, so deeply and seriously immersed in the study and collecting of works of art as to be less at home with the Central European aristocracy from which he sprang than in the society of scholars and art lovers whose professional conversation most interested him.

One can to some extent trace the factors which influenced the style of the collection; the rise and decline of particular interests and the constancy of others can be detected by following the sequence of acquisitions. The Kunsthistorisches Museum was undoubtedly an impressive and constant source of pleasure and study, especially in the pre-war years. Much of his time was also spent studying art in Belgium and Italy, especially in Venice. For advice on acquisitions he turned, always, to Johannes Wilde, and in these years also, and especially for Rubens, to Ludwig Burchard (died 1960). The care of the collection was placed in the hands of the restorer at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Sebastian Isepp, and remained so until the latter's death in 1954. Count Seilern came to depend also on the scholarly advice and the friendship of, in particular, Jan van Gelder and James Byam Shaw. His modesty and his respect for scholarship in others is evident in Count Seilern's post-war catalogue. Indeed, at his request the entries on Titian and Mantegna were written entirely by Wilde, the addenda to the Flemalle Triptych by Jan van Gelder, and all the entries on Claude by Michael Kitson. The entries on the Michelangelo drawings remained unwritten: Count Seilern waited in vain for Wilde to write them. New interests led to, and were perhaps encouraged by, friendship with scholars knowledgeable in that particular field. Certainly, unlike many collectors, he was always ready to relegate a work in his collection to a lesser artist if evidence pointed that way. The Corrigenda volume of the catalogue contains several such instances. Characteristically, he agreed with the view once expressed to him, "ownership is too close a bond". He read voraciously; even in the days of big game hunting his pack-mule would be laden with books. He visited when possible, every exhibition of interest and recorded his opinions in the catalogues; he filled notebooks with accounts of works seen on his frequent travels and acquired an intimate knowledge of the great European public collections as well as many private ones.

By 1939 a substantial number of major works of art had already been acquired. On the brink of war, he was able to move to England with the contents from his house in Vienna, for by then he had relinquished his dual Austro-British nationality and was a British subject. His interests and acquisitions at this date are recorded in two works of scholarship: the unpublished dissertation on Venetian sources of Rubens' ceiling paintings, for which he was awarded a doctorate in 1939, and the catalogue of his paintings (though not the drawings) housed at 6 Brahmsplatz, Vienna IV, which he published in 1937.

The beginnings, in 1928-32, were more modest: a Lotto portrait in poor condition (inv. no.74, not on exhibition), a little Aertsen (2), the Christ crowned with Thorns by a follower of Bouts (7), two van Dycks (20; inv. no.45) and the only Spanish picture (inv. no.255). The only drawings were apparently the Pissarro and a number by Count Seilerns contemporaries, Beni Ferenczy and Gerhart Frankl.

Then, in 1933, the first Rubens paintings were bought (77, 88). One of these was a modello for the Jesuit church ceiling, the project related to the subject of his doctoral thesis. Also, in that year Massys' Madonna entered the collection. A range of drawings were acquired, too, and in the next year were joined by the magnificent Helena Fourment (147) by Rubens, as well as one of the two grand Canalettos (130); the other (129) was acquired in the following year. From 1934 to 1938 one or two Tiepolo drawings were bought each year and the first two of the Aranjuez modelli (111, 113) in 1937. He bought a variety of paintings between 1934 and 1938, including Berthe Morisot, Palma Vecchio, Fetti, Guardi, Titian, van Dyck. Most important of all were the Rubens paintings: the Landscape by Moonlight (89) and the modelli for the wings of the Antwerp Descent from the Cross (64, 65) in 1935, his copies after Raphael's Castiglione (80) and Titian's Charles V (58), Jan van Montfort (85) and The Death of Hippolytus (67) in 1936, two more modelli for the Jesuit church (73, 76) in 1937/8 as well as other modelli (86, 87) and three large panels: the two from the Achilles series (81, 82) and the Conversion of S. Paul from the Munich Museum (69).

Among the drawings, a few by Rubens were added in these years, the first of the Bruegels (View of Antwerp, 127) and the first Durer (The Wise Virgin, 161) in 1936, the first Cezanne (Armchair, 132) and the first Rembrandt in 1937. The Rembrandt belonged to a group of seven drawings bought from Victor Koch. Further drawings by Austrian contemporaries, Ferenczy, Frankl and Wiegele, were also added. Interest in French 18th-century drawings is shown by nearly a dozen acquired at that time. Later this interest waned, though Watteau, with his obvious association with Rubens, he continued to admire. In the mid-thirties, also, the distinguished collection of Chinese bronzes and ceramics was started, largely with the help of Wolfgang Burchard.

Immediately on his arrival in this country, just before the outbreak of war, Count Seilern acquired the first of his two paintings by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (8) as well as the second Rubens landscape (83). He bought for the first time from Kokoschka, the three watercolour Flower Pieces (168), as well as further works by Ferenczy and Wiegele, and he continued to assist Austrian refugee artists and to acquire their works during the next critical decade. The number and quality of paintings, drawings - and illuminated manuscripts - bought during the first few years of the war is remarkable. Throughout, Count Seilern served in the army, first volunteering for the Finns' brief war against the Russians, which was over before he arrived. He returned to this country through occupied Norway and a wide arc of war-torn Europe and joined up as a gunner in the Royal Artillery. By the end of the war, he was serving as an interpreter in Europe.

In the years 1940-42 he nevertheless managed to acquire notable works. Through the assistance of Jan van Gelder he bought in 1940 (and collected in Holland after the war) three Rubens oil sketches from the Koenigs collection, including that for the Whitehall ceiling (59, 68, 84), and in the same year bought the first Michelangelo drawing, the late Crucifixion (172). In 1941 acquisitions included the painting and two further drawings by Cezanne (133, 157), the largest Rubens painting, The Brazen Serpent from the Cook collection (61), and three drawings by him (146, 148), the small Degas (17) and van Dyck (23), the Pissarro and (in 1942) the Renoir landscape. To crown this, in 1942 he bought the beautiful 'Limbourg' Book of Hours and the hitherto totally unknown triptych by the Master of Flemalle, probably the most important single work in the collection.

There followed, not unexpectedly, a few years of quiescence in the growth of the collection. It was transported, with national collections, to the caves of Wales, where Johannes Wilde was among the custodians. Wilde's subsequent internment and deportation as an alien, in the heat of war, to Canada, caused great distress. Only one drawing, a Bruegel figure study (155), seems to have been acquired in the years 1943-44

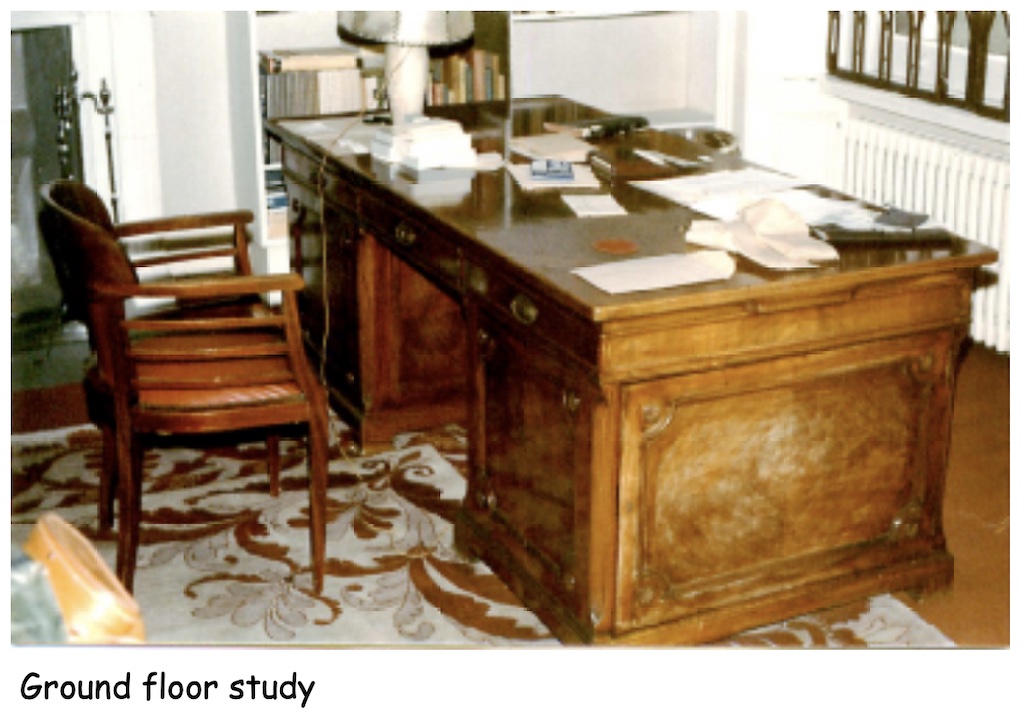

After the war Count Seilern moved to 56 Princes Gate, Kensington, and created there, with the assistance of the frame expert, Paul Levi, a setting for the collection, including a picture gallery for the Rubens paintings reminiscent of the gallery at 6 Brahmsplatz in pre-war Vienna. In 1945 the two finest modelli for Rubens' ceiling in Antwerp (74, 75) were acquired from the Cook collection, and in the following year the entire Fenwick collection of drawings. Count Seilern retained some two dozen of these, ten of which are miniature drawings by Stefano della Bella; others include a Bruegel landscape, the Carpaccio (131), the Leonardo (169) and six by Rubens (including the plant study, 181). There followed a continuous phase of collecting from the late 1940s until a few years before his death, diminishing somewhat as prices rose sharply in the 1960s, and of intensive scholarly study in preparation for the seven volumes of the catalogue published between 1955 and 1971.

His interest in 18th-century French drawings as well as 19th-century French paintings and drawings declined, although in 1954 he purchased Degas' exceptional Lady with a Parasol. He bought no more Cezannes, but this was a source of regret; Cezanne was the only artist of this school for whom Count Seilern retained a deep admiration. No 20th-century paintings or drawings followed after Kokoschka's Prometheus Triptych of 1950, although a number of his illustrated books and portfolios of lithographs were subsequently acquired.

Rubens' art remained a constant source of pleasure and inspiration for Count Seilern.

The Jan Brueghel Family portrait (66) came in 1948 and further paintings were acquired in 1950 (Sacrifice after Elsheimer, 78), 1953 (The Daughters of Cecrops, 70, and The Entombment, 71), 1955 (Cain and Abel, 60), 1958 (Coronation of the Virgin, 72), 1959 (The Annunciation, 63) and 1960 (Cortez, 62). A dozen drawings by Rubens were also bought in the post-war years, as well as a number of works by van Dyck, including the Man of Sorrows (22) in 1967. Pieter Bruegel the Elder he constantly admired, and to the Landscape acquired in 1939 was added a newly discovered grisaille painting (g) in 1952. Count Seilern was able to buy some half-dozen more landscape drawings by Bruegel, as well as figure drawings (the attribution of these is now controversial), in the late 1940s and 1950s.

His enthusiasm for G. B. Tiepolo continued, even increased. In 1949 two further modelli for Aranjuez (114, 115) were added, in the 1950s four paintings (105-6, 108, 116) followed, three more in the 1960s included the last of the Aranjuez modelli (112); the S. Clement (109), bought in 1970, was the latest painting to be acquired in the catalogued collection. On average at least one Tiepolo drawing a year continued to be added, sometimes as many as half a dozen; most were by Giambattista, but a few by Domenico. The majority of the drawings by Guardi were bought in the 1950s, although the only painting by him had entered the collection in 1935*

Just one small Rembrandt drawing had been bought before the war, but from 1947 and for the next twenty years one or more was purchased nearly every year, culminating in Saskia, standing (142) in 1962 and the Seated Actor (177), the last Rembrandt drawing to be acquired, in 1967.

Five Michelangelo drawings joined the first bought during the war: the outstanding Dream of Human Life (139) in 1952, three in 1963-4, including Christ before Pilate (171), and The Virgin and Child (138) among the last acquisitions, in 1970.

In 1951 the first of the small Teniers copies started the series of fourteen, the last added in 1970; two further copies in the series, acquired after 1970, are no longer with this collection. The work of Claude was also a post-war interest, the painting and some six drawings' (134, 158) all bought between 1958 and 1962.

Among the 16th-century Italians the Titian had been acquired before the war; two Lottos (37-8) joined the first in 1949 and 1969; Tintoretto's four paintings and the drawings (152) were all bought between the late 1940s and early 1960s, Polidoro's two paintings and two drawings all in the 1960s, Fra Bartolommeo's nine drawings, including the seven landscapes (124, 154), between 1957 and 1961. Most significant, perhaps, of the post-war acquisitions representing Cinquecento art were the Parmigianinos. Twenty drawings were bought, beginning in 1953 with the beautiful S. Mary Magdalene (173) and continuing until 1970 (one or two drawings by the artist acquired later are no longer with the collection), and the two paintings were added in 1965 and 1966.

The rarity of some of the works bought in the 1950s and early 1960s should remind one of the element of chance in acquisition, such as two Durer drawings (162-3) in 1954 and 1958, Hugo van der Goes' Seated Saint (167) in 1961, Bernardo Daddi's triptych in 1956. The preponderance of drawings, rather than paintings, acquired in the later years reflect, too, the dictates of rising prices and not unlimited funds. High costs and the scarcity of appropriate works of art on the market made it increasingly difficult for Count Seilern in the last years, burdened as he also was by failing health, to acid to the collection. It would now be impossible to create a comparable one.

No collection on so ambitious a scale has been catalogued so scrupulously and devotedly by its owner. His other publications were few: one or two book reviews and articles, including one on The Entombment (71, then just acquired) in the 1953 special 'Rubens' issue of the Burlington Magazine, but the seven-volume catalogue of his much-loved collection is in itself a remarkable memorial to his scholarship.

Helen Braham

XIV

Publications by Antoine Seilern

Catalogues

Gemälde der Sammlung Graf Antoine Seilern, Vienna, 1937.

[A. S.] Flemish Paintings and Drawings at 56 Princes Gate London SW7, London, 1955 (I) Italian Paintings and Drawings . . ., 1959 (II)

Paintings and Drawings of Continental Schools other than Flemish and Italian. ., 1961 (111) Flemish . . . Addenda, 1969 (v)

Italian . . . Addenda, 1969 (v)

Recent Acquisitions . . ., 1971 (VI)

Corrigenda &Addenda to the Catalogue · ·., 1971

Periodicals

'An Entombment by Rubens', Burlington Magazine, xcv, 1953, Pp.380f.

'Ein Fächer für Fürstin Eleonore Schwarzenberg von Karl Goebel', Alte und Moderne Kunst, v, 1/2, 1960, pp.10ff.

'Tiepolo Drawings at the Victoria and Albert Museum' (Review of G. Knox's Catalogue), Burlington Magazine, cm, 1961, Pp.71f.

Dissertation (unpublished)

Die venezianischen Voraussetzungen der Deckenmalerei des Peter Paul Rubens, University of Vienna, 1939.

1981

Sunday Times, July 6th, 1981

1935

Der Morgen

18 February 1935

Page 4

Viennese Africa researchers fight over shares

A battle between the African explorer Bernatzik, Count Antoine Seilern, who is also an African explorer, Baron Bachofen and a Swiss holding company over the majority of a "Yugoslavian" lacquer factory came to public attention last Friday in a trial before the Vienna Execution Court.

300,000 shillings share value

The Swiss Komprum-Gesellschaft, a holding company, had brought an action through Dr. Emil von Hoffmansthal against the outstanding African explorer Count Antoine Seilern for the delivery of 700 shares in the Yugoslavian Ludwig Marxs Lackfabrik A.G. in Domzale, won the case, but could not obtain the shares despite repeated executions because Count Seilern declared that his shareholding was bound in a syndicate. When Dr. von Hoffmansthal turned to the execution court, Count Seilern, who had received a million dollar fortune as the heir of his grandmother, who was the owner of the New-York state newspaper, finally delivered the shares, which represented a value of 300,000 shillings as the majority share. Now the lawsuit over the cost claim continued.

Dr. Bernatzik as share owner

The trial last Friday took an extremely eventful course. The first witness was the director of the "Merkur", Artur Nußbaum, who explained that the shares were actually only valued at three shillings each, but that further increases were necessary because of the majority transactions that had taken place in the meantime.

Dr. Iakubitschek, as the representative of Count Seilern, now tried to prove that the shares did not represent the majority shareholding at all and therefore did not represent the value of 300,000 shillings, since another parcel of 618 was disputed. This parcel belonged to a certain engineer Scherb who lives in Brazil. Baron Adolf Bachofen, the owner of the Maffersdorf brewery, was now questioned about this shareholding.

Baron Bachofen made the interesting statement that he had owned 600 shares and that one day Scherb had come to him and asked him to exchange his 600 shares. Scherb had explained that his own 600 shares were tied up in a minority syndicate to which Count Seilern and Doctor Hugo Bernatzik belonged. The famous researcher Dr. Bernatzik had originally belonged to the majority syndicate of the Marx brothers, but had later switched to the camp of the minority syndicate.

Baron Bachofen testifies

Baron Bachofen did in fact sell off his 600 free shares because Scherb declared that he would be able to make a living overseas by selling the 600 shares.

After some time, however, it had turned out that the interim certificate had not been issued correctly. It would never have occurred to Baron Bachofen to conclude the exchange under these circumstances.

The hearing was adjourned for further evidence on the value of the shares. In the meantime, however, the Swiss holding company has acquired more than half of the shares, so that the battle for the Yugoslavian joint-stock company has already been decided in favour of Komprum.

1989

Our thanks to the Nazis

Art, Brian Sewell, Evening Standard, Thursday 31 August, 1989

‘The last war was a filthy business, but without it this country would have remained a cultural backwater much longer'

This is a year of two famous anniversaries to be celebrated with beano and bacchanal - first the French Revolution, and now, far more significant and sinister, the Second World War.

Its ghosts are still with us. With his grim rhetoric, Winston Churchill informs the present Prime Minister's attitude to Europe -''We will fight on the beaches ... " Mitterrand's impatience to win the battle for that Europe is a cacafuego performance that would have us overlook the collapse and treachery of the French when the Germans swamped the Maginot Line.

The Germans still suffer corporate guilt for their treatment of the Jews, the Slavs, the homosexuals and those with Christian consciences or Communist loyalties whose lives they extinguished in their gas chambers and whose bodies guttered into greasy smuts up furnace chimneys.

The Allies dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese and we too have ever since suffered corporate guilt. So stricken are the our consciences that though they lost the war, we let them win the peace, to hold us in commercial and industrial thrall while we strive to forget the Burmah Railway and their prison camps.

One, of the consequences of the French Revolution was that a vast number of paintings and works of art came to England to be handled by our efficient art. market, and many of them stayed here.

One of the consequences of the Nazi quest for Aryan purity was that so significant a number of their art historians fled here, that the frail foundations of art history as an academic discipline in this country were suddenly secure, and for a generation or so the Courtauld and Warburg Institutes were the world's leading centres of such scholarship.

I was fortunate to sit at the feet of some of these historians and 3 September is as good a date as any to recall their memory with piety and gratitude; to one, Johannes Wllde, I owe most for it was he who taught me that art history is not the mere discipline of dates and documents, but an adventure into the spirit and humanity of man.

If I have any insight into Michelangelo and Leonardo, Rubens and Rembrandt, it springs from the sensibilities as well as the scholarship of old Johannes, tall and stooping, his hands atremble, his accent heavy, his command of English quite poetic, his demands of us as students patiently formidable and gently humorous .

Thinking it possible that this saintly man might turn spy or Quisling, we shipped him to Canada across a U-boat haunted sea, there to be interned as an agricultural worker; but after the war we made amends, appointed him Professor, made him Deputy Director of the Courtauld lnstitute, let him loose on the great collections of old master drawings in Windsor Castle and the British Museum, and decorated him with a CBE.

He published very little, and the students who loved his gentle presence and infinitely subtle mind have only his few essays on Venetian painting and Michelangelo to support their fragile recollections.

Few now know of his influence on Antoine Seilern, the Anglo-Austrian aristocrat of whom the authorities were marginally less suspicious during the last war, allowing this rumbustious body and brilliant connoisseur to serve as a soldier in the Pioneer Corps.

Wilde turned him from his taste for big game hunting and the Mercedes SSK into a scholarly judge of paintings with an eye for sensuality who could and did use his weaIth to form the unparalleled collection of masterpieces that he left to the Courtauld Institute in 1978 (MicheIangelo, Brueghel Rubens, Rembrandt)

In the foreword to his catalogue, Seilern wrote: "Lastly, Johannes Wilde ... deeply felt gratitude for many years of unfailing friendship, and for all that he has done for me ... I have relied with the utmost faith - always rewarded - on his guidance ... I have sought his opinion before acquiring nearly every work of art, and have never regretted it. What merit there is in the collection is due to his counsel. So it is with the greatest sincerity that I say, thank you."

Other such names have faded with familiarity and neglect. Who now remembers that a real man with a sparkling mind – Aby Warburg - brought from Germany the great library of intellectual mysteries that forms the other baroque jewel in the crown of London University, the Warburg Institute?

Fritz SaxI, Grete Ring, Otto Demus, RudoIf Wittkower, Leopold Ettlinger and Nikolaus Pevsner all are fast disappearing from the minds of those who now pursue their academic discipline and who never knew the reasons for their being here and not in their native European homes. Of that great generation only Ernst Gombrich remains.

The Iast war was a filthy business, but without it this country would have remained a cultural backwater much longer. The Nazi persecutions in Germany and Central Europe immeasurably enriched our lives, not only in my small field of art history, but in orchestral music, opera, drama, literature and broadcasting.·

To the ghosts of the many exiles who fled here and stayed to leaven the cultural lump that we had become between the wars, let me echo Seilern's simple gratitude to Wilde "Thank you. Thank you all."

• The Courtauld Institute Galleries were to have opened in their new premises in Somerset House later this year, but are now 40 weeks behind on a 71-week schedule of building works; when this is finished, most of Count Seilern's collection will be accessible for the first time.

The Mail on Sunday, March 7, 1999

Hunt for secret Nazi loot in Britain’s top institute of art

Revealed: Why the Courtauld Gallery is examining the racist past of its founders and up to 100 major works of art have come under suspicion

Art world is under Hitler's shadow

By Nick Fielding, Chief Investigative Reporter

THE world-renowned Courtauld Institute of Art is investigating whether dozens of its most famous works came from collections looted by the Nazis.

The disclosure that paintings by Old Masters such as Rubens, Cezanne; Renoir, Seurat and Pissarro could have been sold to the gallery by unscrupulous dealers after being confiscated from Jewish collectors between 1933 and 1945, or simply stolen by the Nazis as they marched across Europe will shock the art world.

Following the National Gallery's revelation last week that it is holding about 120 paintings for which 'full provenances' do not exist, it puts Britain's huge artistic legacy under the international spotlight.

With high profile exhibitions such, as the Monet at the Royal Academy now a central part of the nation's life, questions have been raised over the many rare treasures on show.

The suspect paintings adorn the walls of the Courtauld Gallery at Somerset House in the Strand in London. Their total worth is incalculable, but until now, their background has never been questioned.

A Mail on Sunday investigation has revealed that the Courtauld Gallery's 70-year history began with benefactors who reflected the anti-semitism that was rife among the Establishment as Hitler rose to power.

The driving force behind the formation of the Courtauld is widely thought to be the textile millionaire of that name.

But in fact the real power was Arthur Lee, later Lord Lee of Fareham, a man of humble origins who, through marriage to a wealthy American, became a force in British Liberal politics before dedicating himself to expanding a collection of rare art.

It was Lee who lived at Chequers, now the Prime Minister’s country home. He donated the house to the nation in ,1921. But he was virulently anti-Jewish, as many in society were at that time.

The Courtauld was his baby. He gave part of his enormous collection of Renaissance art and silverware to the gallery while alive, the rest on his death.

Lee's donations now form a major part of the permanent, much admired, Courtauld Gallery collection . But some works are now under suspicion in a climate which has led the art world to audit its collections for fear they were stolen by Hitler's henchmen.

Another major donor to the Courtauld was Count Antoine Seilern, whose art collection - mainly of Old Masters - was bequeathed to the gallery on his death in 1981. Its value then was conservatively estimated at £50 million.

It was known as the Prince s Gate collection after the London street in which he lived and was never shown publicly during his lifetime. It was generally recognised as one of the greatest bequests of modern tunes and included 128 paintings and 228 drawings by such artists as Leonardo da Vinci, Pieter Brueghel the Elder, Michaelangelo, Rembrandt, Cezanne and Picasso.

Seilern was an Austrian who fled from Vienna to Britain at the beginning of the war. Although not Jewish he had spent much of the Twenties and Thirties in Britain and America and his cosmopolitan background and wealth made him a target for the Nazis.

He joined the army and served as a private in the Pioneer Corps. But he continued to buy and sell art, dealing particularly in Old Masters.

His intimate contacts with art dealers throughout Europe enabled him to purchase paintings that, from 1939 onwards, became available in Switzerland and occupied Holland at extraordinarily low prices. We now know that much of this art had been looted by the Nazis. Whether Seilern was aware of this is a question that still has to be answered.

He inherited his money from his wealthy American grandmother who made a fortune investing in the early years of the American railroad boom.

He was a colourful figure who went big-game hunting in Africa and roared around London on a huge motorbike, often arriving at art lectures, even in his sixties, with his crash helmet dangling from his arm.

A number of his paintings are now thought to be 'problematic', a term used in the art world to define works feared to have been stolen by the Nazis.

He gave 32 paintings by Rubens to the Courtauld Gallery, three of which are now suspect. These include The Bounty Of James 1 Triumphing Over Avarice, a preparatory sketch for his series of four paintings on the ceiling of the Banqueting House in Whitehall.

It is accepted that the three works originally belonged to Franz Koenigs, a Jewish Dutch-German banker who amassed a huge collection between 1918 and 1939. This was seized following Germany's invasion of Holland and Koenigs himself was thrown under a train and killed by Nazis in 1941.

But it is the route the art works took from Holland to Seilern's substantial collection in 1940 that is now the subject of scrutiny.

The Koenigs family is determined to prove that its once fabulous collection was plundered. Koenigs' granddaughter Christine, has already launched legal action in Holland, to recover family paintings which were seized by Hitler and Goering during the War and which are now in a Dutch museum. '

Last week she began proceedings against an anonymous Swiss collector who paid £48.8 million - the highest price ever for a painting - for Van Gogh's Portrait of Dr. Paul Gachet on the grounds that it, too, had belonged to her grandfather.

She claims her grandfather was forced to sell hundreds of paintings and drawings at a fraction of their true value. The family is aware of the Rubens at the Courtauld, Gallery.

Christine Koenigs has visited the gallery to see the painting, and been given full access to its records. At present there is no indication that she intends to launch a legal claim.

At least one other drawing at the gallery, donated by Seilern and believed to have origins in Poland, is under suspicion.

This is The Emperors Charlemagne And Sigismund by the great German medieval master Albrecht Dürer. It is thought to be connected to the controversial Lubomirski drawings which were looted from Lvov in 1941 by the Nazis and personally taken by Hitler.

After being recovered by the Americans from the Alt Aussee salt mine in 1945 they were handed over to the Lubomirski family which had once owned them, instead of the Lubomirski Museum.

Over the years the family sold off the drawings and many were subsequently acquired by museums in Europe and America, including the British Museum, New York's Metropolitan Museum and the National Gallery of Canada.

Yesterday the Courtauld Gallery's director, John Murdoch, told The Mail on Sunday that out of its collection of 520 paintings up to 50 are under investigation to determine their ownership during the war years.

A further 50 drawings by artists including Rubens, Dürer, Tiepolo and Rembrandt also have gaps in their backgrounds.

He added that 23 paintings donated by the textile millionaire Samuel Courtauld, bought between 1929 and 1947 and for which the gallery does not have a full provenance, are also being investigated. They include such famous Impressionist pictures as Pissarro's Lordship Lane Station, Seurat's Pecheur sur Bateau Amarré and Sisley's Seine Landscape.

Mr. Murdoch said the picture audit had been taking place for some time. There's no mystery here. We have already written to the Museums and Galleries Commission telling them which of our artworks have gaps in their histories. Of course, if it turns out that we are holding artworks which prove to have been looted, we will have to come to some kind of arrangement.

The trustees hold the collection in the public trust and they have an absolute obligation to maintain it in the public domain for the use, scholarship and enjoyment of the citizens of the world.'

He stressed that the collection had been formed in good faith.

The admission that major galleries are concerned that they may unwittingly harbour stolen paintings follows representations by Culture Minister Chris Smith and Lord Janner of the Holocaust Educational Trust.

Last November it prompted the National Museum Directors’ Conference to draw up a statement on ‘Spoliation of works of art during the Holocaust and World War II period'.

This acknowledged that the wrongful taking of works of art was one of the many horrors of the Holocaust and the Second World War and reaffirmed that museums should not acquire or exhibit any stolen or illegally exported works.

Yesterday Janice Lopatkin, director of the Holocaust Educational Trust, praised the action of the Courtauld and the National galleries. She said: 'What they are doing is incredibly important. They are assessing their' collections responsibly. I hope it encourages others to do the same.'

The Courtauld Gallery is rightly proud of its role at the forefront of British art. In recognising that some of its major works may have a dubious past, it is ensuring that it retains its hard-won reputation.

2003

The Getty Museum, the world's wealthiest gallery, is being accused of putting pressure on a leading British institution to "tear up" the will of its greatest benefactor.

By James Morrison, Arts and Media Correspondent, The Independent, 09 February 2003

The Getty Museum, the world's wealthiest gallery, is being accused of putting pressure on a leading British institution to "tear up" the will of its greatest benefactor.

Eminent art historians claim the Courtauld Institute is accepting "cash for paintings" by allowing the Getty Museum to ship Old Masters to California for up to a year in exchange for a multi- million-pound donation. The proposed deal is in direct contravention of the bequest of Count Antoine Seilern, an Austrian aristocrat who fled the Nazis to settle in England.

The count left the Courtauld some 350 drawings and 32 Old Master paintings when he died in 1978. The bequest, one of the greatest ever made, includes several classically inspired works by Rubens, among them Cain Slaying Abel and The Conversion of Saint Paul. It also comprises further Flemish masterpieces, including three Van Dycks, a drawing by Michelangelo, Manet's Au bal and paintings by Degas, Renoir, Cézanne and Kokoschka.

His will dictates that no panels dating from before 1600 should ever be shown outside the Courtauld, and those from 1600 onwards should only be loaned within London. But the Courtauld is discussing the loan of the Seilern – or Princes Gate – Collection to the Los Angeles-based Getty Museum. To make this possible, the Samuel Courtauld Trust, which manages the institute's collections, has applied to the Charity Commission for leave to alter the bequest.

Britain's leading art experts have condemned the "deal", which comes only months after the Getty gave the Courtauld an estimated £8m.

Sir Dennis Mahon, the distinguished art historian and a trustee of the National Gallery, said last night that the Courtauld was accepting "cash for paintings". He said: "There has to be a connection between the two things." Sir Dennis is one of 20 figures who have written to the commission objecting to any attempt to alter the bequest.

"I knew the count, and he had very strong views about the wisdom of transporting pictures," he said. "To request to change his will in order to get hold of some cash is quite wrong, and I believe that's what has happened."

His view was echoed by Michael Hirst, a former professor of art history at the Courtauld and a personal friend of the late count. Professor Hirst, now retired, who was based at the institute for 36 years, said: "I feel that the changes violate the wishes of Count Seilern only 25 years after his death." "The proposed amendments on loans would be unacceptable to most conservators," he added, "given that many of his paintings and works on paper are well over 400 years old."

The author of another letter sent to the commission, who wishes to remain anonymous, accused the trust of embarking on a "trashing of wills". And last night, relatives of the count warned that any alteration of the terms of the bequest might be met with a demand from the family for the pictures to be returned. Alexander Seilern, a great nephew of the count, said: "I'm totally against this. I also think there is a clause somewhere saying that, if they do something like that, the deal is off."

Sir Adam Butler, the chairman of the Courtauld Trust, denied the request to change the count's will was in any way linked to the Getty's recent donation.

The trust, which was recently granted independence from London University, had already embarked on its application in order to give it greater flexibility to show its collections elsewhere, as a means of raising its profile. "One thing you do achieve by this kind of thing is that the work acts as a kind of ambassador and helps attract people to Britain and to your institution, which in our case charges for entry," he said. "We have to generate income to keep our gallery and to support the work of the institute."

However, of negotiations between the Courtauld and the Getty over the latter's donation, he said: "The Getty said, 'Obviously, we would like to be able to exhibit some of your paintings.'" Included in that was talk of "wonderful" work from Count Seilern's bequest.

The Getty's director, Deborah Gribbon, said last night: "This is an issue for the Courtauld Institute, not the Getty. I can say categorically that the Getty's relationship with the Courtauld is in no way contingent on having loans from the Princes Gate Collection."

Dictionary of Art Historians

Seilern, Antoine, Count

Full Name: Seilern, Antoine, Count

Other Names: Antoine Count Seilern und Aspang

Count Antoine Seilern

Count Antoine Edward Seilern und Aspang

Date Born: 17 September 1901

Date Died: 6 July 1978

Place Born: Farnham, Surrey, England, UK

Place Died: London, England, UK

Home Country:

Austria, UK

Overview:

Collector and art historian. Seilern was the son of Count Carl Seilern und Aspang (1866-1940) and Antoinette Woerishoffer (Seilern und Aspang) (1875-1901). His mother, who was American by birth, died shortly after his birth. Seilern was raised by his grandmother in New York and Vienna, enjoying dual citizenship of Austria and England. At the end of World War I, however, he renounced his Austrian citizenship. Seilern graduated from the Realgymnasium in Vienna in 1920 continuing on to the Wiener Handelsakademie (1920-1921 where he likely met another future art historian, Fritz Grossmann) and then, beginning in 1922, at the Technische Hochschule, studying for the engineering certificate, (though 1924). Seiler briefly worked in lumber harvesting companies in Yugoslavia and finance in Vienna. His friend the art collector Count Karl Lanckoronski, encouraged Seilern to collect as well. In 1931 a vast inheritance from his grandmother ensured his life leisure. Between 1930 and 1933 he made a world tour, lingering in Africa for big-game hunting. In 1933, a family friend and art historian Count Karl Wilczek recommended Seilern for private study with Johannes Wilde. Seilern enrolled at Vienna University studying under Karl Maria Swoboda, Julius Schlosser, and Hans Sedlmayr. Seilern’s collecting had blossomed on a grand scale, advised by Ludwig Burchard and Wilde. His Rubens' paintings included "Landscape by Moonlight" (onced owned by Sir Joshua Reynolds), numerous Rubens's drawings and modelli, and Tiepolos. Seilern completed his Ph.D. in 1939 with a dissertation on the Venetian influences on Rubens's ceiling paintings. Seilern’s (sole) British citizenship and the annexation of Austria by the Nazi's the year before, both enabled and forced Seilern to return to England in 1939 together with his considerable art and book collection.

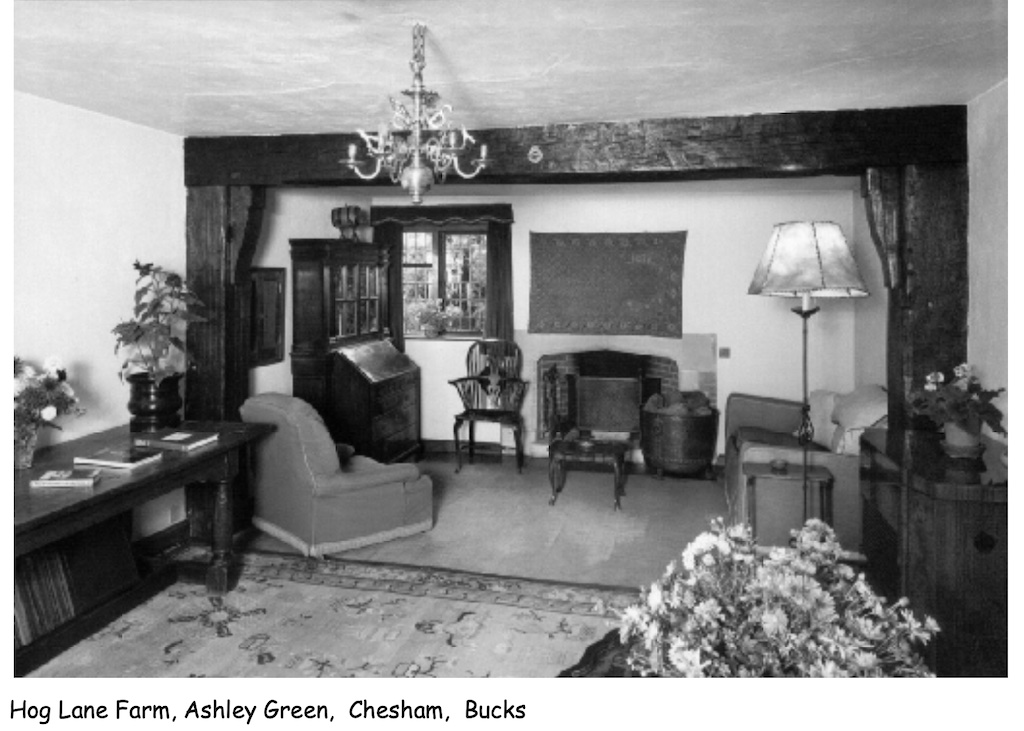

Wilde, who's wife was Jewish, was also in peril. Seilern made arrangements for Wilde's books to be shipped as well. He and Wilde, who had been sponsored by Kenneth Clark (q.v.), reunited in Aberystwyth, Wales. During World War II, Seilern enlisted in the British army and volunteering for the disasterous Russo-Finnish campaign of 1940. He escaped occupied Norway completing the War as a German interpreter. At the height of the War, Seilern made one of his finest acquisitions The Entombment with Donor and the Resurrection by the Master of Flémalle, which he purchased in 1942 as an Adriaen Isenbrandt. After the War, Seilern lived in South Kensington, London, (and a farm near Chesham, Buckinghamshire), building his collection. His drawings included those by [Giovanni] Bellini, Brueghel, Dürer, Hugo van der Goes, Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Watteau, Degas, Picasso, and Cézanne, and even Chinese bronzes. His friend and mentor, Wilde, now deputy director of the Courtauld Institute, convinced him to leave the bulk of his paintings to the Courtauld Institute. Other works went to the National Gallery, London, and the British Museum, but like the Courtauld bequest, completely annonymously. These included Bernardo Daddi's Virgin and Child with Saints, 1338, (purchased 1956). Seilern was a very generous benefactor to the museums, notably the National Gallery, London, and the British Museum, but insisted his gifts remain anonymous, referred to simply at the "Prince's Gate Collection." Beginning in 1955 Seilern published a catalogue of his collection. The seven volume work was completed in 1971. He died of heart disease at age 78 and was buried in Frensham churchyard, the place of his birth. However he was later exhumed and re-interred at a family vault at Schönbühel, Austria, west of Vienna. His archives were placed at the Courtauld Institute.

Home Country: Austria/United Kingdom

Sources: Blunt, Anthony F. "Antoine Seilern: Connoisseur in the Grand Tradition." Apollo 109 (January 1979): 10-23; Farr, Dennis "Seilern und Aspang, Count Antoine Edward (1901-1978)." Oxford Dictionary of American Biography; Shaw, James Byam. "Count Antoine Seilern (1901-78)." The Burlington Magazine 120 (November 1978): 760-2; "Count Seilern's Flemish Paintings and Drawings." Burlington Magazine 97 (December 1955): 396-8; Levey, Michael. "Count Seilern's Italian Pictures and Drawings." Burlington Magazine102 (March 1960): 122-3; Braham, Helen. "Introduction." in, The Princes Gate Collection. London: Courtauld Institute Galleries, 1981, pp. vii-xv.

Bibliography: Paintings and Drawings of Continental Schools Other than Flemish and Italian at 56 Princes Gate London, SW7. London: Shenval Press, 1961; Flemish Paintings & Drawings at 56 Princes Gate, London SW 7. London: Shenval Press, 1955; Italian Paintings and Drawings at 56 Princes Gate, London SW 7. London: Shenval Press, 1959; Recent Acquisitions at 56 Princes Gate, London SW7. London: Shenval Press, 1971.

Estate: Early Chinese Ceramics, Archaic Bronzes, Paintings and Works of Art: the Property of the Estate of the Late Count Antoine Seilern, sold by Order of Beneficiaries. London: Christie's, 1982.

Selected Bibliography:

Flemish Paintings & Drawings at 56 Princes Gate, London SW 7. London: Shenval Press, 1955; Italian Paintings and Drawings at 56 Princes Gate, London SW 7. London: Shenval Press, 1959; Paintings and Drawings of Continental Schools Other than Flemish and Italian at 56 Princes Gate London, SW7. London: Shenval Press, 1961; Recent Acquisitions at 56 Princes Gate, London SW7. London: Shenval Press, 1971.estate: Early Chinese Ceramics, Archaic Bronzes, Paintings and Works of Art: the Property of the Estate of the Late Count Antoine Seilern, sold by Order of Beneficiaries. London: Christie's, 1982.

Sources:

Ludwig Münz another Austrian art historian fleeing Hitler. Wilde, who's wife was Jewish, was also in peril. Seilern made arrangements for Wilde's books to be shipped as Wilde struggled to leave himself. He and Wilde, who had been sponsored by Kenneth Clark, reunited in Aberystwyth, Wales. During World War II, Seilern enlisted in the British army volunteering for the disasterous Russo-Finnish campaign of 1940. He escaped occupied Norway completing the War as a German interpreter. At the height of the War, Seilern made one of his finest acquisitions, "The Entombment with Donor and the Resurrection" by the Master of Flémalle, which he purchased in 1942 as a work attributed to Adriaen Isenbrandt. After the War, Seilern lived in South Kensington, London, (and a farm near Chesham, Buckinghamshire), building his collection. His drawings included those by [Giovanni] Bellini, Brueghel, Dürer, Hugo van der Goes, Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Watteau, Degas, Picasso, and Cézanne, and even Chinese bronzes. His friend and mentor, Wilde, now deputy director of the Courtauld Institute, convinced him to leave the bulk of his paintings to the Courtauld Institute. Other works went to the National Gallery, London, and the British Museum, and, like the Courtauld bequest, completely annonymously. These included Bernardo Daddi's "Virgin and Child with Saints," 1338, (purchased 1956). Seilern's anonymous gifts are referred to simply in those museums as coming from the "Prince's Gate Collection." Beginning in 1955 Seilern published a catalogue of his collection with the assistance of Grossmann. The seven-volume work was completed in 1971. He died of heart disease at age 56 and was buried in Frensham churchyard, the place of his birth. He was later exhumed and re-interred at the family vault at Aspang, Austria, south of Vienna. His archives were placed at the Courtauld Institute. "Count Seilern's Flemish Paintings and Drawings." Burlington Magazine 97 (December 1955): 396-8; Levey, Michael. "Count Seilern's Italian Pictures and Drawings." Burlington Magazine102 (March 1960): 122-3; Braham, Helen. "Introduction." in, The Princes Gate Collection. London: Courtauld Institute Galleries, 1981, pp. vii-xv; Farr, Dennis "Seilern und Aspang, Count Antoine Edward (1901-1978)." Oxford Dictionary of American Biography; Shaw, James Byam. "Count Antoine Seilern (1901-78)." The Burlington Magazine 120 (November 1978): 760-2; Blunt, Anthony F. "Antoine Seilern: Connoisseur in the Grand Tradition." Apollo 109 (January 1979): 10-23.

1978

Orbituaries

Count Antoine Seilern (1901-78)

“And this, or something like it was his way.”

Burlington Magazine

Antoine Seilern, who died at 56 Princes gate on sixth July, was one of the most discriminating, and one of the best informed, of the great collectors of the present century. The collection of paintings and drawings by the Old Masters that he gathered chiefly in Britain, and has bequeathed to this country, will be enjoyed by many for the first time, when it is eventually shown in public here; and many will be astonished that works of such great quality we are not already more widely known; but the growing army of art historians will have been aware for some time of what was in store for them, from an acquaintance with the catalogue that he completed so carefully with his own hand, from his researchers, so modesty written, so splendidly illustrated, and so admirably produced, between 1954 and 1971. But the catalogue and the collection will be appraised in the Burlington Magazine by another pen, in due time; my present purpose is to attempt some account of the collector himself.

He was born on 17th September 1901 at Frensham Place, near Farnham in Surrey, the third son of an Austrian noblemen, Count Carl Seilern, and his wife, Antoinette Woerishoffer of New York. His mother died five days after his birth, and it was from his American mother that Count Antoine inherited his share of a large fortune, which enabled him to devote much of his life to the collection of works of art, and to the studies, academic in the best sense, that he considered the necessary corollary of enlightened collecting. His debt to his grandmother is affectionately recorded in the dedication of the printed catalogue. But he had connexions in England too. His aunt, his father's sister Ida, was married to Philip Hennessy, whose sister Nora was the wife of the late Lord Methuen ; and when that distinguished Academician (‘Cousin Paul’ as Seilern called him) exhibited paintings or drawings at Colnaghi’s on two or three occasions, Seilern always bought one for the sake of the connexion. He had very little interest in contemporary British art, and I think these purchases were usually given away to other members of the family.

His father, Count Carl, had taken British nationality in 1898 or 1899, about the time of his marriage; And all three sons, having been born in England, had British nationality by right; But they were all christened in the Austrian embassy in London, and so acquired Austrian nationality as well, which they kept until the end of the First World War. After their mother's death and some years in England, the boys were sent to their grandmother in New York; They returned to their father, now married again, in Vienna in 1910; And there, two years later, their grandmother Mrs Woerishoffer, joined them. She took charge of them again until 1916, when the United States came into the war and she had to return to New York. All the boys now remained in Austria and continued their education there.

As a very young man in the 1920s, in Vienna and elsewhere, Count Antoine shared his elder brother's interest in horse racing and shooting; he hunted game in Africa and the Yukon, obtained an air pilots certificate in Berlin, and was much in society. It might have been hard to guess his future. But his father and stepmother (to whom he always remained devoted) encouraged him to study the history of art at Vienna University, and he was enrolled there from 1933 to 1937. His professors were Schlosser and Sedlmayr; and the young Johannes Wilde - on the recommendation of a family friend, Count Carl Wilczek - gave Seilern private tuition which was the beginning of all his more serious interests and a lifelong friendship. Wilczek himself was an art historian; and I also remember in Vienna in 1930 another friend of the Seilern family, the old count Karl Lanckoronski, who's example may have had some influence in turning all Antoine Seilern’s thoughts towards collecting on his own account - a gigantic man of great charm, most hospitable in showing to a young stranger the fine collection of paintings and sculpture that he himself had gathered in the Lanckoronski Palais.

Seilern’s subsidiary subject at the University - surprising, perhaps, but vouched for by his old friend, Jan van Gelder - was Kinderpsychologie, taught by a lady who was a pupil of Freud. The subject of his dissertation in art history was Die venezianischen Voraussetzungen der Deckenmalerei des Peter Paul Rubens. His progress in the subsidiary subject is not recorded; but the work of Rubens, of course, remained his passion for the rest of his life. He had not quite finished his doctorate when the Nazis arrived in Vienna in 1938; and the political events that followed meant a great upheaval in his life, still more in the lives of his friends. Ludwig Burchard and Sebastian Isepp , with their families, Baron Martin Koblitz , and, finally, Johannes Wilde and his wife, all came to this country before him ; It was only in the summer of 1939, just before the Second World war began, that he himself arrived, having at last, to his great satisfaction, achieved his University degree. His passport was British, and when the war broke out, though he was 38 years old, he enlisted in the ranks of the British army. He served for a time abroad, before the German invasion of Holland, in the Royal Artillery, and on some attachment to the intelligent Intelligence Corps, in which he was afterwards commissioned. But he had managed to bring his own paintings, drawings, and furniture (and the Wilde’s furniture) from Vienna; and well before the end of the war, so far as his military duties allowed, he was settled in England.

Professor van Gelder, who may be his oldest surviving friend, has given some account of these events in a letter to Sir Anthony Blunt, who has kindly allowed me to make use of it. Van Gelder himself, on the very eve of the German invasion of Holland in May 1940, contrived to buy for Seilern (from the Koenigs Collection) three Rubens oil sketches, which he then deposited as Swedish property in an Amsterdam bank, and handed over to him when the war ended. Seilern already owned important paintings and drawings; at the Oppenheimer sale in 1936, for instance, he had bought one of the most beautiful of Dürer’s early drawings, the Wise Virgin of 1493; but the greater part of his collection was acquired after he had settled in England. Even in the middle of the war - in the summer of 1942, when he happened to be on leave in London - he secured (with Burchard's help) one of his greatest treasures, the small triptych by the master of Flémalle, sold at Christies as an Isenbrandt.

After the war, he occasionally competed in other important sales dash at Sotheby's in 1957, for instance, getting the lion's share of the fine series of landscape drawings by Fra Bartolommeo that appeared from an unknown source, in an album collected by the Florentine, Francesco Gabburri. But in general he liked to buy privately, or as things were offered to him in London. He never bought in a hurry and never from a photograph; he considered the attribution, the condition, the relative importance. He mastered the relevant literature, and he had good judgment; but he seldom bought a Rubens without Burchard's advice, or any other painting or drawing without Wilde’s. To both these ….

* Besides Sir Anthony Blunt and Professor Jan van Gelder to whom I have made acknowledgements, I am greatly indebted for help in writing this to Count Charles Seilern, Count Frederick Seilern and Mrs Allan Brabam.

The Times, 12th July 1978

OBITUARY

Count Antoine Seilern

Collector of Old Masters

Sir Anthony Blunt writes:

Count Antoine Seilern, who died in a London nursing home on July 6, was probably the greatest European collector of old Masters in the post-war period.

He was born in England of Austrian parents and studied the history of art at Vienna University under the late Johannes Wilde, who became his close friend and his mentor in the formation of his collection.

He lived in Vienna till the Anschluss of 1938, when he moved to England, a country for which he had a profound affection and which he had frequently visited. On the outbreak of war, he volunteered for military service, but owing to his dual nationality - British and Austrian - he was only accepted for the Pioneer Corps in which he served as a private.

The war naturally interrupted his collecting activities, but not entirely, since he was for much of the time stationed not far from London. In fact, it was during the war - actually in 1942 - but he made one of his most important purchases, a triptych by the master of Flémalle, one of the most important Flemish Primitives in this country.

After the war, guided by Wilde, he returned to collecting with passion, and his London house soon came to contain a collection which was unique in containing a series of exceptionally fine paintings brought together round a central theme on a carefully thought out at historical plan. The centre of his interest was Rubens, by whom he eventually owned 33 paintings and 22 drawings, covering all periods and all types of painting, except the very large religious or historical canvases which would have been too big for the house. He extended his range to works by artists who Rubens admired and studied, including in most cases drawings as well as paintings. Among the Flemings were Matsys, Pieter Bruegel the elder and Rubens own pupil Jordaens; The northern Italians included Bellini, Mantegna, Titian, Palma Vecchio, Tintoretto and Parmigianino. Room was represented by drawings by Michelangelo, Florence by Leonardo. In addition, the collection included a magnificent 14th century altarpiece by Bernardo Daddi, a large group of drawings by Rembrandt and works by Degas and Cézanne. The works of art were a superb illuminated manuscript from the studio of the Limbourg brothers, a 6th century BC geometric Hydra and a number of Chinese bronzes. Seilern also commissioned a series of large decorative paintings from Kokoschka, who was a personal friend. He had an unfailing sense of quality and his collection included not only the major paintings mentioned above but exceptional works by relatively minor artists, such as Menzel and Rudolph von Alt.

As a man he was very retiring and avoided the limelight as far as possible. He would always show his collection to anyone whom he believed to be genuinely interested, and he regularly allowed groups of students from the Courtauld Institute and elsewhere to visit his house. He had, however, one violent prejudice: No dealers were allowed to visit the house (the only exception was one who was a close personal friend, through whom he made many of his acquisitions). His generosity, particularly to refugees from central Europe, was enormous, but in this as in all else he carefully avoided any publicity. Only those who benefited by it can appreciate its extent and the delicacy with which it was carried out.

He was also generous to museums and institutions, but it is hard to estimate the extent of his gifts because they were always made with the minimum of publicity, and usually anonymously period two of the most important can however be mentioned. In 1945 he presented to the National Gallery the fine full-length portrait of the first Earl of Denbigh by Van Dyck, and about the same time he bought the magnificent collection of drawings formed in the early 19th century by Sir Thomas Phillips, which had passed by descent to Thomas Fenwick, took out a small number of drawings by Rubens to add to his own collection and gave the remainder to the British Museum. This gift was in part an expression of his admiration and affection for the late A. E. Popham who was at that time keeper of the Print Room.