Charles F. Woerishoffer

Fifty Years in Wall Street

Henry Clews

Chapter XL

Charles F. Woerishoffer

The Career of Charles F. Woerishoffer, and the Resultant Effect upon Succeeding Generations.

The Peculiar Power of the Great Leader of the Bear Element in Wall Street.

His Methods as Compared with those of Other Wreckers of Values.

A Bismarck Idea of Aggressiveness the Ruling Element of His Business Life.

His Grand Attack on the Villard Properties, and the Consequence Thereof.

His Benefactions to Faithful Friends.

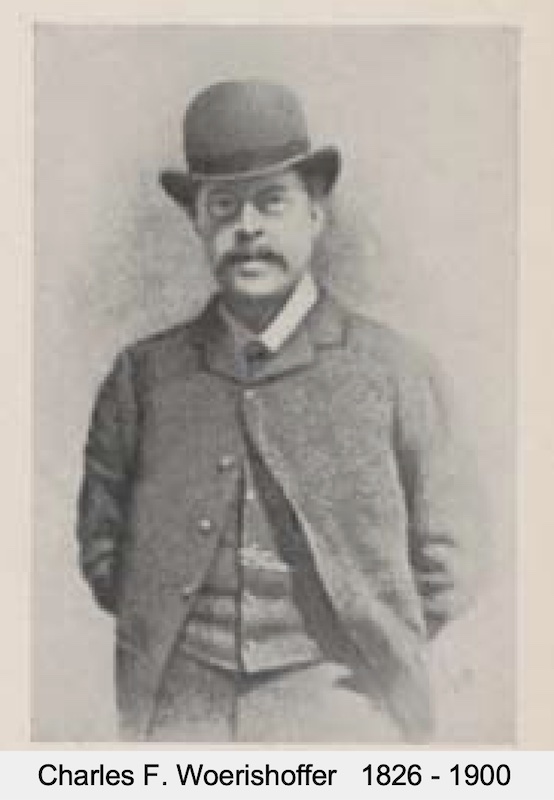

By the death of Charles F. Woerishoffer, Wall Street lost one of the most prominent figures which has ever shown up here. Mr Woerishoffer died May 9, 1886. His career is one worthy of study by watchers of the course of speculation in this or any other country. The results of his life work show what can be accomplished by any man who sets himself at work upon an idea, and who devotes himself steadily and persistently to a course of action for the development and perfection of the principle which actuates his life. Mr Woerishoffer possessed peculiar personal qualities which are denied to most men and to all women. He had the magnetic power of impressing people with confidence in the schemes which he inaugurated; that is to say, he had the power of organization-the same power has made other men great, and will continue to make men great who possess it in all walks of life. Notable instances may be cited in the cases of Bismarck, Gladstone, Napoleon, Grant, and coming down to WalI Street proper - Gould, Daniel Drew, old Jacob Little and the Vanderbilts, especially the Commodore, in his superior power of aggressiveness.

It has been said of Mr Woerishoffer that he was fortunate. He was indeed. He was fortunate in the possession of natural ability, and he had the aptitude to take advantage of events, and associate circumstances and the strength of purpose, and to direct, instead of following, the operations with which he became connected. He was the leader of the bear element of the Street-at least he was such during the period which marks his successful operations here. There is no doubt that the death of Mr Woerishoffer was hastened because of the great strain of mind growing out of his business transactions. There is one point in this connection which has been overlooked by his biographers, namely, that his boldness in the magnitude of his dealings was resultant from a careless or non-calculative mind. I do not believe that Mr Woerishoffer ever undertook a speculation of any sort until he had carefully calculated all the chances pro and con, and his success, remarkable as it was, was largely due to the combination of calculation and the natural development of business conditions, of which he was a close student.

Mr Woerishoffer's conception of business principles was iconoclastic to an intense degree. As a broker, as a business man, as an operator in stocks, he "believed in nothing;" that is to say, he was a believer in the failures of men, and had no faith in the corporations and enterprises which were organized for the purpose of the development of the best interests of the country in which he lived. There is another view, or another statement of this peculiar feature, of the character of this man which may be given in description, and this is illustrative of the careful study he made of everything passing along in the lines of life with which he was connected. It is this: That Mr Woerishoffer, by his intimate study of the prospects and probabilities of the projected plans of enterprising Americans, had come to the conclusion that the majority of them must fail, and that the first flush of enterprise would be changed to a darker shade as time progressed. That is to say, he saw and knew a great deal of the organization of the railroad schemes which have marked the growth of our rapid development in a business way, and he judged that the inflated ideas of the projectors must meet with a check as developments were made, and that the earning capacity of the roads would not equal expectations. Hence he sold the stocks, and sold them right and left from the start, and with his followers reaped the profits. Woerishoffer never indulged in the finesse of Gould or Henry N. Smith. He had the German ideas of open fight, and he attacked everything indiscriminately, losing money sometimes, but making money at other times, and by his open dash and persistency carried his point.

There is no doubt that the successful career of a man of this sort has a deleterious effect upon those who follow him in succeeding generations. It does not matter how successful the development of the business industries of this country may be hereafter, there will always be found men who will speculate upon the ruination rather than the success of the best interests of the country merely because Charles F. Woerishoffer lived and made a fortune by his disbelief and his disregard of the growth of the institutions of the country which gave him a home.

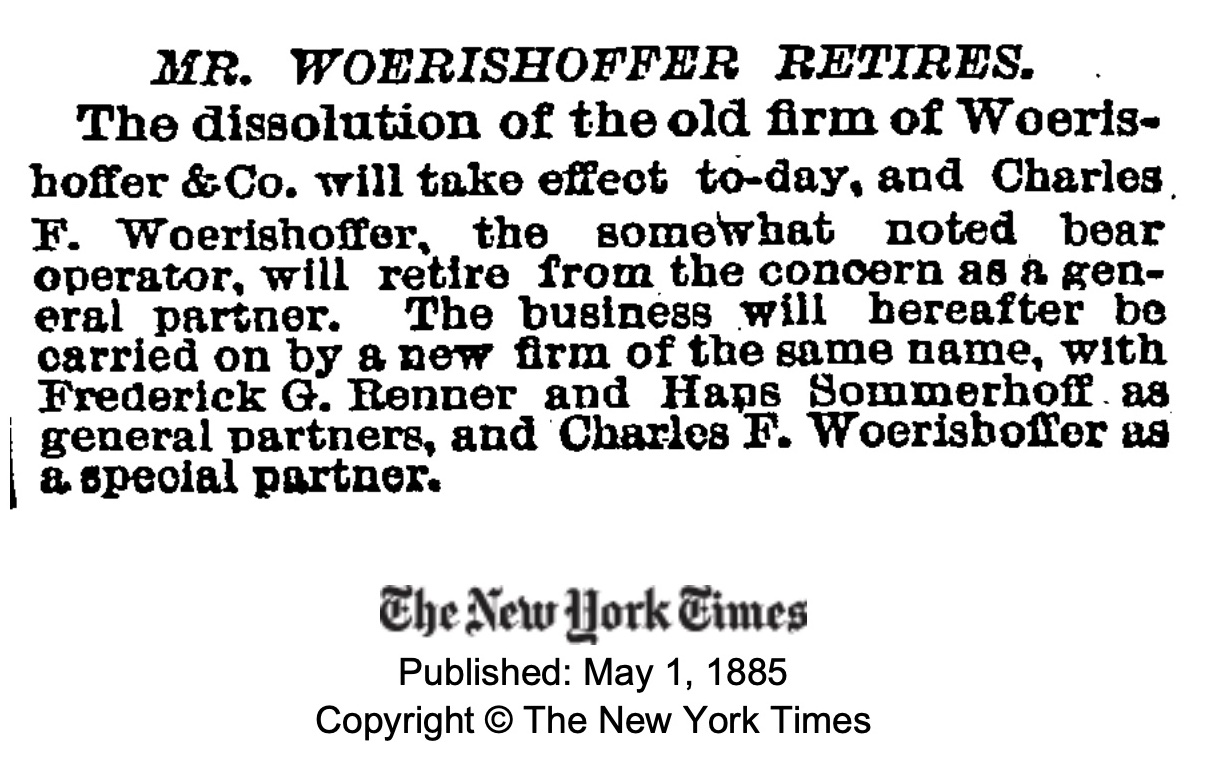

Woerishoffer was a wonderful example of the sudden rise and steady and rapid progress of a man of strong and tenacious purpose, who adheres with firmness to one line of action or business. He was born in Germany. Woerishoffer's Wall Street career was begun in the office of August Rutten, afterwards of the firm of Rutten & Bond, in which Woerishoffer subsequently became Cashier. He left this firm in 1867, and joined M.C. Klingenfeldt. Mr Budge, of the firm of Budge, Schutze & Co., in 1868, bought him a seat in the Stock Exchange. Some time after he entered the Board he became acquainted with Mr Plaat, of the well-known banking firm of L. Von Hoffman & Co. Mr Woerishoffer was entrusted with the execution of large orders, especially in gold and Government bonds. At that time the trading in these securities was very large. Afterwards Plaat became an operator himself, and Woerishoffer followed in his footsteps as an apt pupil. Eventually he formed the firm of Woerishoffer & Co., his first partners being Messrs. Schromberg and Schuyler, who made fortunes and retired.

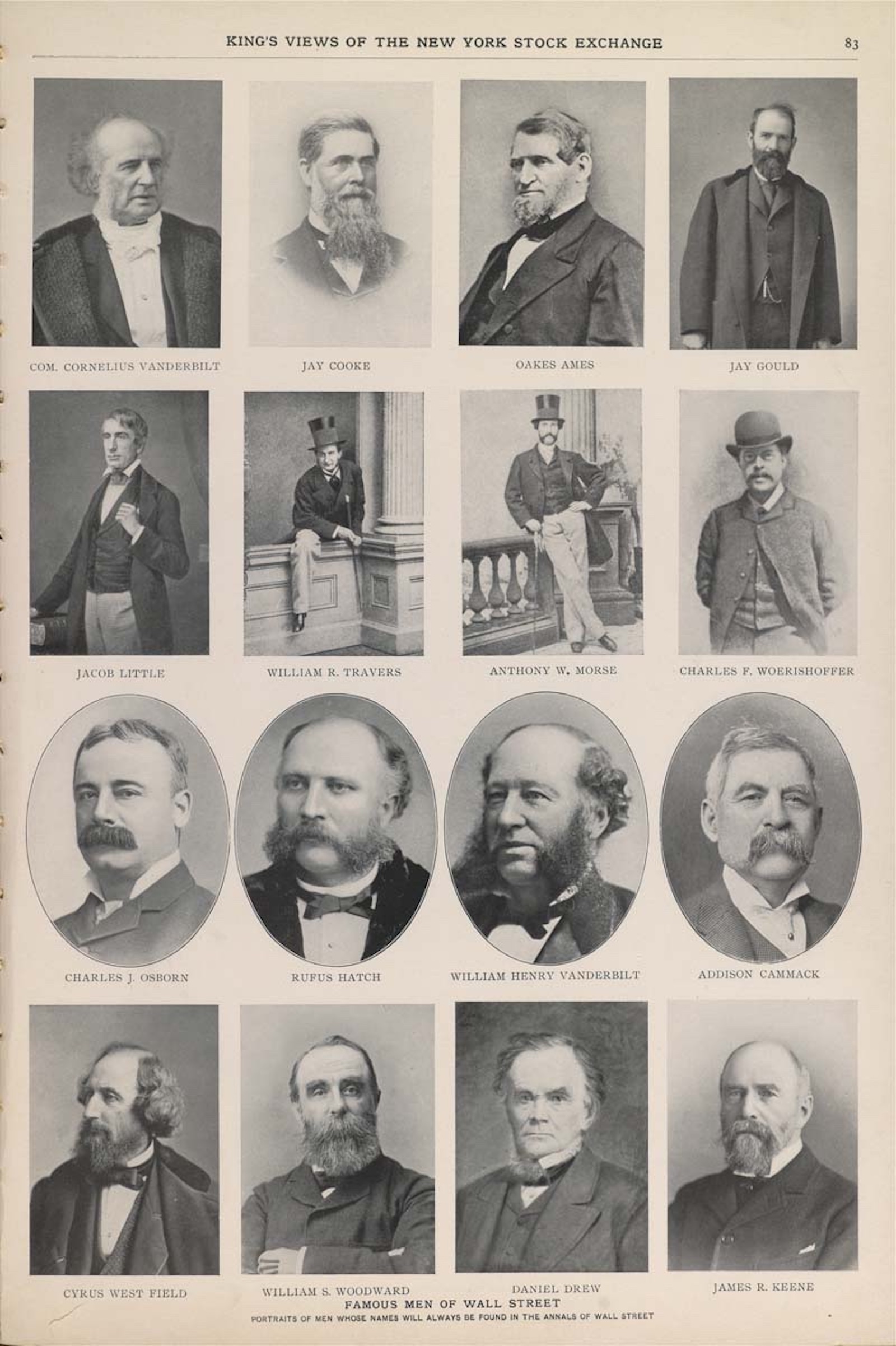

Woerishoffer was connected in enormous operations with some of the magnates of the street; for instance, James N. Keene, Henry N. Smith, D. P. Morgan, Henry Villard, Charles J. Osborn, S. V. White, Addison Cammack, and last, though not least, Jay Gould. He was especially on intimate terms with his great brother bear, Addison Cammack, both speculatively and socially. Besides being a bold operator in the street, Woerishoffer was associated with large railroad schemes, which gave him the inside track in speculation. He was connected with the North River Construction Company, the Northern Pacific, Ontario & Western, West Shore, Denver & Rio Grande, Mexican National, several of the St. Louis Companies, and Oregon Transcontinental. He was originally a rampant bull on these properties until they began to get into trouble, and then he became a furious and unrelenting bear. He smashed and hammered them down right and left. He soon covered his losses and began to make enormous profits on the short side of the market. On the bonds and stock of the Kansas Pacific, when it became merged in the Union Pacific, it is supposed that Woerishoffer cleared over a million dollars.

Woerishoffer, it seems, was one of the first to propose the building of the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad. On this enterprise he realized immense profits for himself and his friends. The stock rose until it reached 110, and was "puffed" up for higher figures. The public was attracted by the brilliant prospects of immense profits on the long side. Mr Woerishoffer and friends held large quantities of long stock, but sold out, and afterwards put out a large line of shorts. The bear campaign had Woerishoffer as leader, and, it is said he succeeded in covering as far down as 40, and some even lower. In 1878, when the market began its great boom on account of the resumption of specie payment and the general prosperity of the country, he organized a combination which bought stocks largely and sold wheat short. On this deal he made large profits, and began to develop into a pretty strong millionaire. He took advantage of the shooting of President Garfield, in 1881, together with his colleagues, Cammack and Smith, to organize a bear raid on a large scale, which was probably one of the chief, although somewhat remote, causes of bringing about the panic of 1884.

The great perspicacity which he had in the deals enumerated failed him in 1885. He thought, as the wheat crop was small, that wheat would go up and stocks would go down, but the very reverse occurred. The disappointment and depression, very probably, resulting from this brought on the aneurism of the heart, which killed the great bear operator, and his death was a fortunate event for Wall Street.

One of the many things which gave Woerishoffer great reputation as a speculator, both here and in Germany find England, was the bold stand he took in the fight for the control of Kansas Pacific against Jay Gould, Russell Sage, and other capitalists, railroad magnates and financiers in 1879. He represented the Frankfort investors, and had engaged to sell a large quantity of Denver extension bonds at 80, to the Gould-Sago syndicate. The syndicate, how ever, knowing that they had the controlling influence, declared the contract for 80 off, and "came to the conclusion, after examining the road-bed, that the bonds were not worth more than 70," and they would not take them at a higher figure. Woerishoffer then made a grand flank movement on the little Napoleon of finance and his able lieutenants. He seemed to be greatly put out that they had broken their contract, but did not complain very bitterly. He immediately cabled to the English and German bondholders and soon secured a majority of the bonds which the syndicate wanted, and deposited them in the United States Trust Company. He then informed the syndicate that they could not obtain a single bond under par to carry out their great foreclosure scheme. It was this circumstance that caused Frankfort speculators and investors to come so largely into the New York stock market, and that also made English capital flow in freely, speculators throwing off their former timidity. The amount involved in the Gould-Sage syndicate deal was about $6,000,000 of bonds, thus netting Woerishoffer considerably over a million. This deal at once gave him an international reputation as a far-sighted speculator, and this reputation was gained at the expense of Gould and Sage, owing to their disregard of the contract which had been entered into.

Woerishoffer showed great sagacity as a speculator when Henry Villard put forward his immense bubble scheme in Northern Pacific and the Oregons. Although invited to go into the big deal with other millionaire speculators who had taken the Villard bait so freely, Woerishoffer kept prudently aloof, and looked on the players at the Villard checkerboard with equanimity and at a safe distance. He was not then considered of very much account by the men of ample means who so freely subscribed $20,000,000 to the Villard bubble. At the moment when these subscribers were so highly elated with the idea that the Villard fancies were going far up into the hundreds and, perhaps, the thousands, like the bonanzas during the California craze, Woerishoffer boldly sold the whole line" short." This was a similar stroke of daring to that which James R. Keene had perpetrated on the bonanza kings in the height of their greatest power and anticipations. The Villard syndicate determined to squeeze Woerishoffer out entirely, and for this purpose a syndicate was formed to buy 100,000 shares of stock. There were various millionaires and prominent financiers included in the syndicate. These were the financial powers with which Woerishoffer, small in comparison, had to contend single-handed. The feat that Napoleon performed at Lodi, with his five generals behind him, spiking the Austrian guns which were defended by several regiments, was but a moderate effort in war compared with that which Woerishoffer was called upon to achieve in speculation. He took things very coolly, and with evident unconcern watched the actions of the syndicate. The latter went to work vigorously, and soon obtained 20,000 shares of the stock which they required. It still kept climbing rapidly, and so elated was this speculative syndicate with the success of its plans that it clamored for the additional 80,000 shares, according to the resolution. The speculators thought they were now in the fair way of crushing Woerishoffer, and with a hurrah obtained the 80,000 shares required, but Woerishoffer's brokers were the men who sold them to the big syndicate. It was not long afterwards that the syndicate felt as if it had been struck by lightning. In a short time the Villard fancies began to tumble. The syndicate was in a quandary, but nothing could be done. It had tried to crush Woerishoffer. He owed it no mercy. The inevitable laws of speculation had to take their course, and the great little bear netted millions of dollars. These events occurred in 1883.

After the Villard disruption, Mr Woerishoffer became conservative for some time, and was a bull or a bear just as he saw the opportunity to make money. When the West Shore settlement took place he watched the course of events with a keen eye, and was one of the most prominent figures in pushing the upward movement upon the strength of that settlement. His profits on the bull side then were immense. After this he became a chronic and most destructive bear. The reason he assigned for his conversion and change of base was that the net earnings of the railroads were decreasing, and did not justify an advance in prices. He pushed his theory to an extreme, making little or no allowance for the recuperative powers of the country, and the large bear contingent, which he successfully led, seemed to be inspired with his opinions. These opinions, pushed to the extreme, as they were, had a very demoralizing effect upon the stock market, and constituted a potent factor in the depreciation of all values, throwing a depressing influence on speculation, from which it did not recover until many months after Mr Woerishoffer's death. The great bear had wonderful skill in putting other operators off the track of his operations by employing a large number of brokers, and by changing his brokers and his base of action so often that speculators were all at sea regarding what he was going to do, and waiting in anxiety for the next move. It was considered remarkable at the time that his death had not a greater influence on the stock market than this result proved. If he had died a week sooner, his death might have created a panic, for he was then short of 200,000 shares of stock. His short accounts had all been covered before the announcement of his death on the Stock Exchange.

Woerishoffer was almost as famous for his generosity as James R. Keene. It is said that he made presents to faithful brokers of over twenty seats, of the value of $25,000 each, in the Stock Exchange. He made a present of a $500 horse to the cabman who drove him daily to and from his office. He was exceedingly generous with his employees. A short time before his death, feeling that the strain from over-mental exertion was beginning to tell on his constitution, he had resolved to visit Europe for the purpose of recuperating, but, like most of our great operators, he had stretched the mental cords too far before making this prudent resolve and he died at the early age of 43. How many valuable lives would be prolonged if they would take needful rest in time. The death of Woerishoffer should be a solemn warning to Wall Street men who are anxious to heap up wealth too rapidly. His fortune has been variously estimated at from $1,000,000 to $4,000,000. He left a widow and two little daughters.

Woerishoffer had simply the genius for speculation which is uncontrollable, irrespective of consequences to others. He had no intention of hurting anybody, but his methods had the effect of bringing others to ruin all the same. He merely followed the bent of his genius by making money within the limits of the law, and did not care who suffered through his operations. All speculation on the bear side involves the same principle. If there is any difference among speculators, it only consists in degree. Large transactions, like those in which Woerishoffer was engaged, are more severely felt by those who have the misfortune to get "squeezed;" but it all resolves itself into a question of the survival of the fittest.

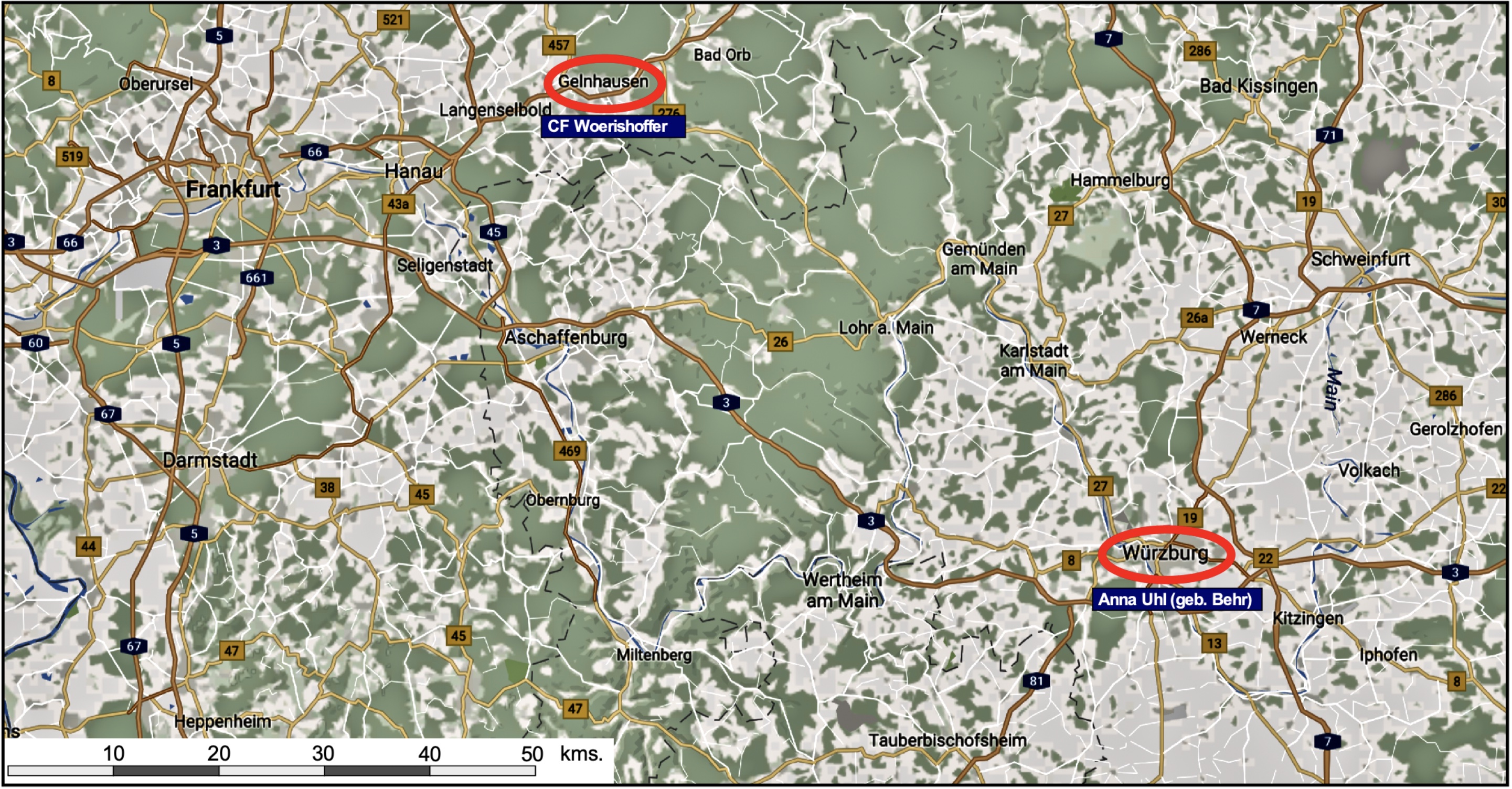

Woerishoffer's success in this country seems strange to Americans, but how much stranger it must have seemed to the people of his native town of Hanau Hesse-Nassau, where he was born in 1843, in comparative poverty. John Jacob Astor was one of the first of a considerable number of Germans to find this country a veritable new EI Dorado, where peasants' sons, as if by magic, became far wealthier than many of the nobility whom they had, as boys, gazed upon with awe. Who could have foreseen such a career for the poor young German, who came to New York in I864?

He was then in his twenty-first year. He had had some experience in the brokerage business in Frankfort and Paris, but he came here poor. Addison Cammack, who was to become his ally in many a gigantic speculation, was then prominent in the South, where he had favored the cause of the people of his State during the war, and had made a fortune. D. P. Morgan, who was to be another of his speculative associates, had already won a fortune by speculating in cotton in London. Russell Sage counted his wealth by the millions. Jay Gould and Henry N. Smith had gone through the feverish excitement of a Black Friday, and either, in common parlance, could have "bought or sold" the poor young German. Nevertheless, by strange turns in the wheel of fortune, he acquired a financial prestige that enabled him to beard the lion in his den, and snap his fingers at powerful combinations that sought to ruin him. When Henry Villard demanded his resignation as a director in the Oregon Transcontinental Company, on the ground that he had been selling the Villard properties short, the "Baron" (as Woerishoffer was often called) tendered it at once, and flung down the gage of battle in the announcement that he would ruin the head of the Villard system.

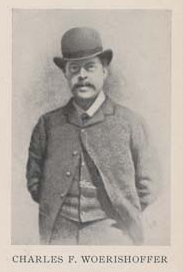

Chas. F. Woerishoffer was slightly built, had a light complexion, was under the medium height, and, on the street, might have been taken for a bank clerk. He showed his inborn love of gaming in many ways. He is said to have bro ken a faro bank at Long Branch twice; he would play at roulette and poker for large stakes. He was kind-hearted and charitable. At Christmas his benefactions to clerks and messenger boys were notable. In the height of a great speculation he sometimes showed extreme nervousness, but during the memorable contest with the Villard party he exhibited the greatest coolness and composure. He was a curious compound of German phlegm and American nervousness.

One of the fortunate events in his career was his marriage, in 1875, with Miss Annie Uhl, the step-daughter of Oswald Ottendorfer, the editor and proprietor of the great German organ of New York, the Staats-Zeitung, who brought him, it was understood, a fortune of about three hundred thousand dollars.

The following circular to my customers, which I published May 13th, 1886, with special reference to the death of Woerishoffer, and its consequences, I think is worthy of reproduction here:

"The future of the market is going to be a natural one, and will go up and down from natural causes; when this is fully realized there will be no lack of the public taking a hand in it. That element has been crowded out of Wall Street for a long time past, largely due to the fact that its judgment to predicate operations has been sat on by brute force. It has been, therefore, made to feel that the market was not one where it was safe to venture. This brute force power came from Woerishoffer, who has for a long time past been the head and front as a leader on the bear side, and was a gigantic wrecker of values. His method was to destroy confidence and hammer the vitality out of every stock on the list which showed symptoms of life, and his power was the more potential, as all the room traders were converted to believe in him and were his followers. His decease leaves, therefore, the entire bear fraternity without any head, and consequently in a state of demoralization, and in a condition not unlike a ship at sea without a rudder. Mr Woerishoffer was a genial, hospitable man, lovely in character at his own home, true to his friends and generous to a fault, and will, therefore, be a great loss as a gentleman; but so far as the prosperity of the country goes, his death will be the country's gain. To the fact that Mr Woerishoffer's power and influence are no longer felt on the market is almost entirely due the change of front of the situation, which is now one of hopefulness. While he lived the public and half the members of the Board were completely terrorized by the fear of him, and were kept in check from being buyers, however much the position of affairs warranted going on the long side. The bull side of the market has had for a long time past to contend with the bold and ferocious attitude of Mr Woerishoffer. When the bulls felt justified in making a rally and forcing the market to go their way, when it looked most encouraging, as a result of their efforts, Mr Woerishoffer would strike their specialty a sledge hammer blow on the head; he would repeat that on every attempt that was made, which finally resulted in discouragement. If ten thousand shares were not ample for that purpose, he would quadruple the quantity; in fact, he has often been known to have outstanding contracts on the short side of the market amounting to 200'000 shares of stock at least. As an operator he seemed to be so peculiarly constituted as to know no fear, and would often turn apparent defeat to success by possessing that tra.it of character. It will be a long time before another such determined and desperate man will appear on the stage to take his place; in the meantime, it will be plainer sailing in Wall Street, besides safer for operators. Mr Woerishoffer, as an operator, was full of expedients. He put his whole soul into his operations, and not only would he attack the stock market with voraciousness, but he would manipulate every quarter where it would aid him; sometimes it would be in the grain market, sometimes by shipping gold, and sometimes by the manipulation of the London market. He had all the facilities for operation at his fingers' ends, in fact he commanded the situation to such an extent as to make his power felt. Mr Cammack, Mr Woerishoffer's associate, while usually a bear, is a very different man and not to be feared, for that gentleman usually sells stocks short only on reliable information, and always to a limited extent. If he finds that the market does not go down by the weight of sales, he soon extricates himself at the first loss. In this method of doing business lies his safety. In this way he will sell often 10, 20 or 30 thousand shares of stock and make the turn, but will not, like his late friend Woerishoffer, take a position and stand by it through thick and thin, and browbeat the market indefinitely until it finally goes his way. At the present time, therefore, the bulls have no great power to fear whenever they have merit upon which to predicate their operations.

The future will be brighter for Wall Street speculators and investors than it has been for a long period, and with the public who may be expected to come again to the front, greatly increased activity should be the result."

May 1, 1885

May 11, 1886

C. F. WOERISHOFFER DEAD

WALL-STREET LOSES ONE OF ITS GREATEST LEADERS.

TAKEN AWAY IN THE MIDST OF ACTIVE BUSINESS PLANS - THE CAREER OF A SUCCESSFUL OPERATOR.

A sudden hush fell on the bustling Stock Exchange yesterday mourning. The Chairman's gavel had fallen and Commodore James D. Smith, the Exchange's Vice-President, stood on the rostrum sad-faced.

"It is my sad duty," he said, "to announce to you the death of our fellow- member. Charles F. Woerishoffer."

The effect was electrical. A gloom such as had not been seen in that busy room in years settled on every hearer's countenance.

"His associates." continued Commodore Smith, " lose a genial companion and a generous friend. This floor is deprived of a fearless leader and a successful man; his family mourn a devoted husband and father and this community and this country suffer the loss of a valued citizen."

Woerishoffer dead! It was more than any of the 500 men on the Exchange floors could readily believe. He was active among them only a day or two ago. His speculations - famed these many years and all the world over for their dash and fearlessness, and, most of all, for their success were still in progress. It seemed idle to announce the death of one whose activity was still shown here and there and everywhere through all the interwoven complexities of Wall-street. Yet the solemn visage of the Vice-President there on the rostrum proved that their ears bad heard aright. Business stood still. Brokers who had rushed into the board pell-mell to buy and to sell loitered, negligent of money-making occupation. Had the grave of some one dear by the tie of blood to each man present been opened there deeper solemnity could scarcely have prevailed. It was a scene never seen on Stock Exchange floors before.

The life of Charles Frederick Woerishoffer was one crowded with exceptional incidents. His career in Wall-street in more than one respect was without parallel. He was a poor clerk in August Rutten's office, with neither relatives nor influential friends on this side of the water, after he had passed his twenty-first year. Death found him at the age of 43, a power in money centres, the ruler of corporations, the maker of markets, a man possessed of millions. Every penny of all his wealth, every iota of his far-reaching influence he made for himself. And he made it all in Wall-street.

For some time Mr. Woerishoffer suffered much from physical troubles that he hoped to end by a trip that he had planned to make this Summer to his Fatherland, where life at Carlsbad's springs was to be enjoyed. He did not feel compelled to give up active business, though, and in despite of his physician’s counsels he bravely visited his offices day by day und kept up a prominent part in the greatest or Wall- street's speculations. But a severe cold clutched him a fortnight ago and a week ago last Saturday he quit the Street - he thought for a day or two's recuperation, in reality for his deathbed. Since that day he remained closely within doors at the suburban home of Mr. Oswald Ottendorfer, his wife's stepfather, under the care of Dr. Jacobi, his family physician. Symptoms of pneumonia assailed him, but used to desperate chances, the sick man did not worry over his condition. Not until last

Friday, when he spit blood, would he consent to admit that his family had reason for apprehension. Then he remained in bed, confessing himself an invalid, but still full of hope and buoyant spirits. His mind was fixed on the prospective European trip; he was serene in every regard, save that he feared he might be inconvenienced by having to postpone the voyage temporarily. On Sunday Addison Cammack, Charles D. Keep, and other personal friends called and received assurances that he was not in danger, but before Sunday midnight came word that Mr. Woerishoffer was dead.

He lay quietly in bed a little after 9 o'clock, chatting with his wife and getting much comfort from contemplation of the plans for the prospective voyage when all of a sudden be started up as if stung by some acute pain and half whispered "I feel faint". His little children playing by the bedside quit their sport startled by their mother's cry. The wife was bending over her husband who had fallen back upon his pillow unconscious, while blood burst through his lips. Before a quick alarm could summon medical aid Mr. Woerishoffer was beyond the reach of earthly help. A group of physicians, gathered at his bedside found that a blood vessel had broken.

Mr. Woerishoffer was born at Gelnhausen in the Province of Hesse in 1843. He came to this country a lad to seek his fortune. His entrance to Wall-street was in 1885 as the clerk of August Rutten, who still remains a Stock Exchange figure. Capacity brought young Woerishoffer forward, and he was soon Mr. Rutten’s cashier. It was not long before he began to push out for himself. He gained some prominence associated in 1888 with M. C Klingenfeldt, and a year or two later Mr. Budge, of Budge, Schutze & Co. won by the young man’s pushing ways, bought him a seat in the Stock Exchange. Then L. Von Hoffman & Co. trusted him with important business, found their trust amply repaid, and the poor clerk of a few years before began to found his fortune. Then the firm of Woerishoffer & Co. was formed. It was prosperous form the start. Two of the first partners soon retired rich. It has been noted for its influence. Now its founder dies and leaves his business in the hands of trusted friends, his partners Hans Sommerhoff and F. G. Renner.

One of the things which won repute for Mr. Woerishoffer was a fight he waged in 1879 with Jay Gould, Russell Sage, and other capitalists interested in securing control of the Kansas Pacific Railroad Company. Mr. Woerishoffer, as a representative of Frankfort investors, had contracted to sell certain Denver extension bonds to the Gould-Sage syndicate at 80. But representatives of the syndicate made a trip over the road and decided that it would be to their advantage to declare the old contract off, and they there upon named 70 as the price at which they would take the bonds. Woerishoffer said never a word to the syndicate, but the cables carried quick messages to the English and German security holders, and before the New-York syndicate was prepared for h s campaign he had safely corralled in the United States Trust Company here more than a majority of the bonds that the syndicate was after. Then he calmly turned to the gentlemen who had insisted that 80 was too high and informed them that, in as much as their big foreclosure scheme depended on having the control of these bonds, they would have to pay a little penalty for their quondam coquettishness, and he didn’t let a bond go under 100. That made Woerishoffer famous in Germany and in London as here. About $6,000,000 of bonds were involved in the deal. From that day Woerishoffer was the man trusted implicitly by every German investor in American securities; and to that successful fight was due the fact that Frankfort came largely into the New-York stock market. German capital enlisted largely to support him in the construction of the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad.

It was C. F. Woerishoffer who pricked the famous Northern Pacific bubble which Henry Villard blew up into such size and gorgeousness that men of millions bowed to it. When Mr. Villard was launching with Northern Pacific his long line of Oregon companies, Woerishoffer was courted somewhat at the start, but as he did not become enthusiastic he was soon let severely alone, the supporters of the magnificent Villard schemes believing that he, after all, could not be a factor of much consequence pro or con. He had gravely shaken his head and declared that the earnings of the pet companies did not guarantee the fancy prices at which their stocks were quoted. And he openly sold the whole line short. Arguments having no weight with him, it was determined to punish him and whip him into line, and a syndicate was formed to buy 100,000 shares of stock to squeeze him out of the way. He had a single-handed fight. The financial powers were all on the other side.

D.O. Mills, Drexel, Morgan & Co. and other influential parties were with Villard heartily. Practically he had to face the same strong and astute financiers who recently had tried to show the world that all that is needed to give stocks a value is to bid up the price regardless of all such minor things as net earnings and the like. It was the same tune they played then. And a merry dance Woerishoffer led them. It was in the Summer of 1883, and he was living down at Long Branch, but he used to come to his Wall-Street office daily and watch the tape. Nothing seemed to worry him. Stretched out on his easy office lounge he fanned himself calmly, and whether the ticker showed an advance or fall in quotations, he was never provoked into more than a yawn. Yet, all the time countless friends were assuring him that he was atop of a volcano. The syndicate put in its work sharply. They bought 20.000 of the 100.000 shares, and still Woerishoffer journeyed down to Long Branch in the evening as jaunty and smiling as ever. Then with a rush they bid for the other 80.000 shares. They didn’t bid in vain. Their whole order was filled. Woerishoffer’s brokers filled it. A dazed syndicate it was that met to wonder and talk matters over. Not quite so dazed, though, as they were one afternoon soon after, when the Street began to wake up to the true inwardness of Villardism and the astute financiers found themselves in a hurly-burly panic, with the prices of their sugar-coated stocks going lower and lower and lower, until Woerishoffer, as the master of the situation, had cleared millions of dollars as recompense for his allegiance to the fact that stocks cannot be bulled with much satisfaction for any length of time with net earnings out of the question.

Mr. Woerishoffer led to success again in a dozen notable campaigns that followed. He had a comprehensive mind, and was neither chronically a bull or a bear. Last year he was closely identified with the "West Shore Settlement" and was one of the conspicuous leaders in the movement that pushed prices upward. He made large sums of money on the bull side then. Lately, however, he came out strongly as an ardent bear on the situation. Having exceptional sources of information, he became possessed of facts which showed him, he said, that the railroads were not saving net earnings enough to justify advances made in their prices.

The transactions of Mr. Woerishoffer, when interested in special speculation, were tremendous. Where other big operators would sell or buy thousands of shares he handled tens and hundreds of thousands. His brokers were all over Wall-street. It was impossible to detect his hand in the market when he attempted concealment, for his own brokers were never sure but that the man opposite and at cross purposes had precisely the same client. Mr. Woerishoffer's death did not influence the stock market appreciably, as it might have done a week ago, when he was short of 210,000 (?) shares. Every short account in his name had been covered yesterday morning before his death was announced on the stock exchange. He was, however, heavily long of wheat protected by "futures". Woerishoffer's generosity became proverbial long ago. His clerks were the envy of every office in Wall-street. He spent thousands of dollars every month in helping other men. Over 20 seats in the Stock Exchange, - worth $25'000 a piece - have gone to their present owners as out and out gifts from Woerishoffer to brokers he had found faithful. Last Christmas, and it was not exceptional, he distributed one-thousand- dollar checks in his office, gave District messenger boys twenty-dollar and fifty- dollar greenbacks, and sent a handsome five-hundred-dollar horse as a present to the cabby who drove him up and down town daily. His friend "Dan" Worden lately bought his Thirty-ninth-street house, for it was Mr. Woerishoffer's intention, on his return from Europe, to build a palatial home here, as magnificent as architects could plan and unlimited money could construct. He was credited with a fortune from $4'000'000 to $10'000'000. He was a special partner in two or three brokerage firms.

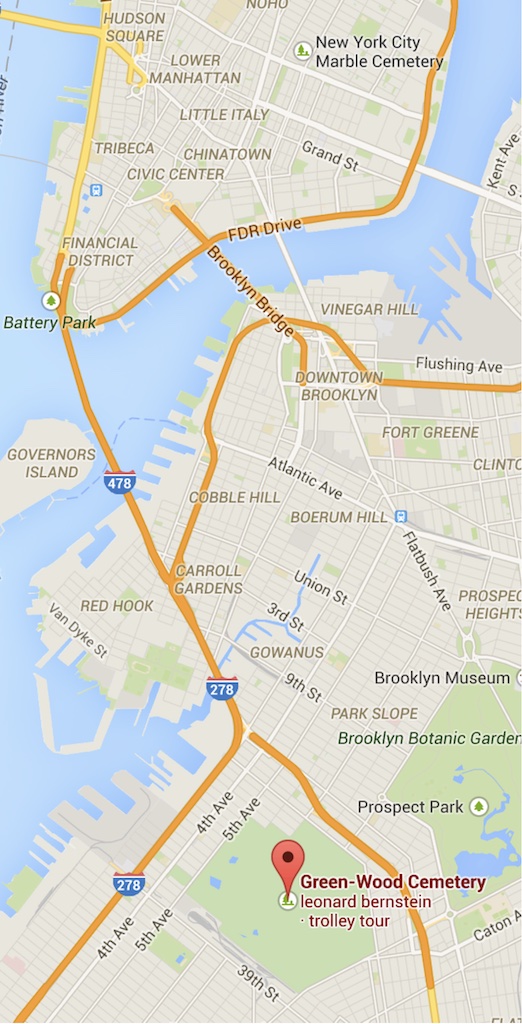

Mr. Woerishoffer married Miss Annie Ottendorfer in 1873(?) at the same country home where he met such sudden death. The wedding was the night before the first day of the great panic, and the wedding trip was prevented by business exigencies that required Mr. Woerishoffer's presence in the Street. They had three children but one boy died. A widow and two little girls survive. Mr. Woerishoffer will be buried in Mr. Ottendorfer's plot in Greenwood. The funeral service will take place at noon on Wednesday in Mr. Ottendorfer's house, No. 7 East Seventeenth-street.

The New York Times

Published: May 11, 1886 Copyright © The New York Times

Note: $10 million in 1884 is worth approx.. $265 million in 2020.

May 16, 1886

C.F. WOERISHOFFER'S WAY

STORIES OF THE GREAT OPERATOR TOLD IN WALL-STREET

ACTS THAT SHOWED THE BIG HEART OF THE PRINCELY SPECULATOR WHO WAS NEVER CAUGHT NAPPING.

Wall Street is crammed with reminiscences of Charles F. Woerishoffer, whose unexpected death has practically kept business much of the time this last week at a standstill on the stock exchange. He was the prince of speculators, as brave as he was bighearted, as amiable as he was dashing. He loved a fight, he gloried in the contest where chances were evenly matched and he was never so happy as when by a hair the sword of an adverse fortune seemed to be hanging fairly and squarely about him. He courted antagonism and enjoyed no victories that have not to be won by brilliancy of plan and execution. Week men were never his prey; he never wheedled ninnies out of money; the shearing of stray lambs he left to men of a different type. When he fought he fought openly. No honest man ever charged that he betrayed anybody.

Woerishoffer hated a hypocrite. An instance of his feelings in this particular was shown not many weeks before he died when he came across a gloomy-faced man down near Stock Exchange, and without ado asked him his trouble. The man told him a story that did not reflect much credit on another Wall Street operator whose name is held high in the vicinity of this town. He had made use of this man, promised him a reward in the way of a stock "privilege" and in the end dismissed him unpaid. How much does he owe you? asked Mr Woerishoffer. The sum was named, and out on Mr Woerishoffer's pocket came a roll of bills promptly; the debt was cancelled and the man sent up the street rejoicing, the bearer of a receipt in Woerishoffer's own handwriting addressed to the high-toned speculator who had broken his word - a rebuke that was felt keenly, too.

Less than a year ago a well-known speculator imposed heavy losses on many stock exchange firms. He had been in many ways conspicuous on the street and had never done much to help anybody along, but on the other hand he owed considerable to the assistance of Mr Woerishoffer in several campaigns; yet when he lay down on his contracts Mr Woerishoffer himself as well as Mr Woerishoffer's brokerage firm were imposed upon. Mr Woerishoffer sent for the man, received him in his private office, and said: "You have not treated my boys right" - meaning young Mr Renner and Mr Sommerhoff, his junior partners. "But I have made their losses all right and you needn't be ashamed to look them in the face. You have put a loss of $25,000 (1) on me as well, and I've cancelled that too. You don't owe this office a cent". The caller looked dazed. A kick instead of such princely generosity was what he had counted upon. But Woerishoffer was not yet done. "Now I hear you are dead broke. I'm sorry to hear that and so I've put $10'000 credit to your name in this office which you can speculate on to get a fresh start whenever you see fit."

A young man, whom Woerishoffer knew and liked, decided three or four years ago to give up the clerkship he held and make a little venture in business for himself on money that he had been able to save out of his salary. Woerishoffer heard of the scheme and sent for the young fellow, who, full of his project, talked freely. When he finished Woerishoffer handed him a slip of paper and bade him goodbye.

On the slip was written this: "To whom it may concern: I will guarantee A.B. for $10,000. C.F. Woerishoffer". Things of this sort were of everyday recurrence. People who knew him aver that $ 1'000'000 is a low estimate of the money that he gave away in unostentatious benefactions during last dozen years. Not less than a score of members of the Stock Exchange hold their $25,000 seats there as a direct outcome of his generosity. Whenever a young broker of promise impressed him by cleverness or faithfulness this was not an unusual way for him to show appreciation. As a matter of form he not infrequently accepted liens upon the brokers' seats, but it leaks out that all such claims have been fully cancelled, and the seats that stand in their names are just as he always intended they should be - their own absolutely.

In his famous Northern Pacific campaign, which sent Henry Villard across the ocean and damaged the fortune and prestige of many another money magnate, Mr Woerishoffer employed continually an army of brokers, and never was there a regiment under better discipline. He kindled enthusiasm in every one of his representatives and one night after a hard day's fight he sent a little message to each of them, saying something like this: "In addition to your commissions I have placed $5'000 to your credit, which you are at liberty to draw at my office at your convenience." Frank Savin was one of Mr Woerishoffer's favourite brokers. During six months of last year Savin's commissions alone footed up $50,000. When it is considered that Savin received but a fraction of Woerishoffer's work, some slight idea can be formed of the tremendous scale upon which he did business and some suggestion comes as to what a factor such an operator was in the stock market.

"There never was such a scene in Wall Street as I used to witness every day during the Northern Pacific fight between Woerishoffer and the Villard-Drexel-Morgan-Mills syndicate," said an acquaintance of Mr. Woerishoffer a couple of days ago. I had the chance to see both sides daily and when the famous 100'000 share pool was formed to buy everything that Woerishoffer dared to sell the gentlemen who invested in it were bubbling over with confidence. There never seemed a surer thing than their success, and I really feel bad for Woerishoffer when I used to see him, so little did he appear to consider the fearful danger he was in. He was never without his smile and jauntiness. A small boy at a circus never got more genuine pleasure out of life than he seemed to be having every day. He knew all the opposition plans and he used to applaud their cleverness: had he been one of the bulls himself their campaign could scarcely have evoked more enthusiasm from him.

Friends advised him to change his tactics: predictions of utter rout and failure were dinned into his ears daily, but he perversely answered every gloomy counsellor with some light sentence that convinced them always that he did not count the chances against him correctly. I was in his office one afternoon just after the last lot of the 100,000–share pool was bought in by the syndicate. I had just left some of the Villard party and they were jubilant over something they had discovered which convinced them that Woerishoffer was weakening.

He had sold them the whole of these 100,000 shares, and they knew that he was short of the market that much and far more. It was then, they felt sure, to be a very easy thing to squeeze him into a position where, if not wiped out completely, he still would be wholly without power to fight further or influence anybody else to fight.

I expected to find Woerishoffer unhappy, so pronounced were the declarations of the gentlemen. I didn't find him in any such way. One of his friends was telling him a good story and he was in rolls of laughter when I dropped into his office. To all appearances he had never heard of any such thing as that an organisation with millions on money for ammunition was out gunning for him.

He was reclining in a big easy chair, equipped with his ever-active palmleaf fan, as happy and careless to all appearance as even the whistling messenger boys who darted in and out through the swinging doors. In rushed a trusted broker, nervous and anxious. The palmleaf went through the air to and fro listlessly as the speculator listened to an excited report of how things were going on the Stock Exchange.

"Well, sell them 20,000 more", quietly said the speculator, amiably, as the broker ended his agitated tale. "Sell them at 20,000 more !". The broker stood aghast, but there was only the utmost unconcern on his principal's face, and the palmleaf never flurried in its regular oscillations. "Sell them 20,000 more."

And Woerishoffer really yawned as if he were bored somewhat by a trifle. An observer could never have surmised that the man coolly ordering his broker to sell "20,000 more" had just been listening to a tale that was filled with reports that Wall Street's expectation was on tip-toe, momentarily awaiting his failure.

But Woerishoffer's courage and confidence where infectious always in their effect upon men about him, and that broker sped away, not seeing things much clearer than before, but strong with a new enthusiasm. And another broker staggered in to take his place, bringing similar anxieties and the same tales of Wall Street anticipation. "Sell them 20,000 more". The first order duplicated. The man seemed not to realise really that it was serious business that he was transacting for the man who had been interrupted in his funny story was invited forthwith to resume, and applause and merriment never came from a free-hearted man more earnestly than from Charlie Woerishoffer.

On the Stock Exchange what a scene! A very tempest raged. Fury was in every pool, and brokers with Woerishoffer orders were paralyzing everything and everybody. Down, down, down began to fall the toppling quotations – desperately as did the rich syndicate fight – and he who was laughing merrily in his office over a tale well told had ample reason for other satisfaction before he went to his Long Branch train that night. The Villard bubble was pricked. Woerishoffer was master of the Stock Exchange, the possessor of millions of money that but yesterday had been collected to crush him. “Sell them 20’000 more”. There was the keynote of Woerishoffer’s campaigning always. He was never pushed to a point where the fighting spirit was squeezed out of him. When the “best felt that they finally had him at the end of his rope there always came out the echo of that “20’000 more” war cry, and a new lease for himself new discouragement for opponents, was in order. It was always so. He never hesitated because obstacles seemed big to the casual eye. Yet nothing is surer than that Woerishoffer always reconnoitred before he charge. Before he sold a single share of the Villard stocks short he had assured himself of the innate rottenness of the corporations, so far as their not earnings went and it was only after he saw clearly that public information as to their real condition would ruin the big schemes afoot to bull them that he notified Mr. Villard and Mr. Villard’s co-partners in the bull deal that he would have to antagonize them.

There was the secret of his phenomenal coolness and confidence in the face of what seemed unconquerable odds when Wall Street stood waiting, minute by minute, for his bankruptcy.

When Henry N. Smith and William Heath failed last October the Street was filled with rumors that Mr. Woerishoffer would be found involved, having had a big joint account with Smith, on which it was claimed that Mr. Morosini and others of Smith’s and Henth’s creditors would be able to hold him responsible. This sort of talk, however, did not last long, for out came a written release signed by Smith long before the failure, showing that the mooted “joint account” had been some time terminated. There never were lacking proofs to show that Woerishoffer was methodical. The men he had around him, his clerks and his partners, were always alive to the needs of strictest discipline. There never was a bit and miss system allowed vogue in any department. But for loyal service how royally he paid! The prosperity of every subordinate was evidence of his big heartedness.

Frank Savin heard one day that Mr. Woerishoffer was about to give up his old house, and he asked if he could rent it. “Yes” was the reply. “at your own price”. “I’ll give you $ 4’000 for the year”. Was Savin’s offer, which was accepted then and there without ado. Time went by: Savin occupied the residence, and at the end of the year handed in his four-thousand-dollar check. Woerishoffer took it, but before Savin went home that night a messenger boy put an envelope in his hand. Inside were four registered United States bonds for $ 1,000 each, two of them in the name of Mr. Savin’s young son and two of them in the name of his daughter. This was the disposition that had been made of the year’s rent – so far as to rent went, for the bonds had been bought at a premium, and the extra sum Woerishoffer had taken out of his pocket to eke out the four-thousand-dollar check.

At the Windsor Hotel one night he got into a discussion with Harvey Kennedy and others over Union Pacific, then selling a good many points higher than it is quoted at now. He was very bearish at it and offered to bet $ 1.000 that it would drop 20 points before the year was out. Harvey Kennedy took the bet and the same bargain was struck with another gentleman, who was aforetime prominent as one of the brokers of James R. Keene. Mr. Kennedy required only one night to sleep on his contract, and before he dined the next day his bet was off. Not so the Keene man. He stuck and got stuck, within six months the Woerishoffer prediction was verified, and the loser betook himself to Mr. Woerishoffer’s office to pay his debt. For some time Mr. Woerishoffer assumed to have forgotten all about the bet, but finally he took the check that was offered, thanked the caller, and seemed to consider the whole thing over. So did the other man; but he was mistaken. That one-thousand- dollar check was simply deposited to the name of the man who drew it, and a notice to that effect went to him just as to any other regular customer of the house; nor would Mr. Woerishoffer listen to any arguments about it when afterward his friend tried to change his mind about such a disposition of it.

A broker who at one time did some business for Mr. Woerishoffer fell sick and was kept away from business a long time. Somebody happened to say in Woerishoffer’s presence one day that this broker was in a bad fix financially, with debt of $ 1.000 or more harassing him and no wherewithal to pay them. Woerishoffer said nothing, but the next morning all those bills were paid. Nor was this an isolated case. A man once his friend was never forgotten. And even enemies received graceful and generous consideration from him always. One man, who after receiving favors at Woerishoffer’s hands secured a place on the staff of a New-York news-paper where he had the chance which he enthusiastically made the most of to assail his aforetime benefactor without stint. Day by day a steady stream of abuse was sent flowing from his pen. Of course Mr. Woerishoffer was not left uninformed of the source of the calumnies. But one day the gentleman of the pen lost his place and found himself confronted by irate creditors. He hadn’t a cent, and things generally wore a pretty dark sort of a visage. Then he did what might not have been much to the credit of his manhood, but which nevertheless showed that he had not been an altogether careless observer of the traits and disposition of C.F. Woerishoffer. He sent a whining letter to the speculator, abjectly asked forgiveness for all the meannesses that he had been guilty of, and whiningly promised to do so no more if only out of goodness of heart Mr. Woerishoffer would “lend” him $100 or $200. Mr. Woerishoffer showed the letter to a close personal friend, and said: “What do you think of that?” The answer did not lack conciseness, but Mr. Woerishoffer didn’t seem to share the spirit of his friend. Instead he said: “I do not want anything to do with this fellow myself, but if he is suffering for lack of money, as he says he is, something ought to be done for him. And I want you to do me the favour of giving him this. “The “this” was a roll of notes twice as big as the sum that had been pleaded for.

HALSTON.

1) http://www.davemanuel.com/inflation-calculator.php

The New York Times

Published: May 16, 1886 Copyright © The New York Times

Note: This article appeared in the NY Times six days after CFW died.

MR. WOERISHOFFER BURIED.

THE FUNERAL SERVICES ATTENDED BY MANY MOURNING FRIENDS.

Wall-street moneymakers looked their last yesterday upon the features of their dead leader, Charles F. Woerishoffer. The funeral service at the residence of Mr

Woerishoffer's father-in-law, Oswald Ottendorfer, No. 7 East Seventeenth-street, was very modestly conducted. High banks of flowers in the rich designs surrounded and surmounted the coffin in the wide parlours, whose works of art where all shrouded. A simple talk by a Minister, tributes to the good sense, the courage, the big-hearted generosity of the dead man, tears from men and from women who had lost a friend – these were all. The plain unassuming tastes en Mr Woerishoffer himself were followed out closely.

Men who are notable in Wall-street and whose names have many years been conspicuous in financial affairs were present.

... there follows a series of names of important New York personalities ...

were all personal friends of the deceased, and showed with undisguised emotion the depth of the loss they felt, scarcely less than the sorrow of the immediate members of the stricken family. The Rev. Dr. Schauffler conducted the services at the house and the Rev. Bartholomew Krusl performed the last rites at the grave in Greenwood.

The New York Times

Published: May 13, 1886

Copyright © The New York Times

Note: Charles Woerishoffer was born in 1844 and died, aged 41, in 1886.

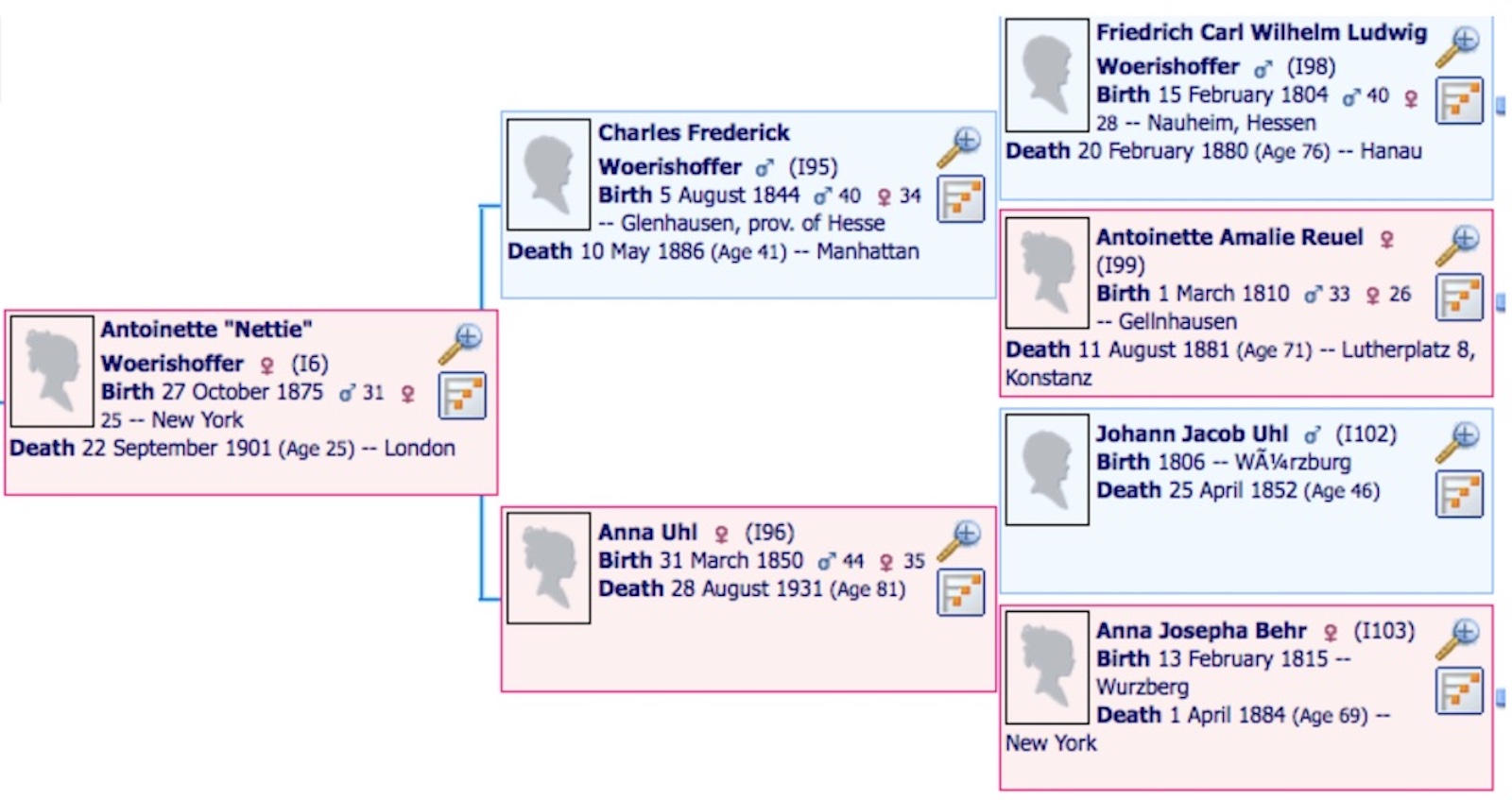

He had a brother - Friedrich (Fritz) 1839-1902 and a sister Antonie Cristine 1845-1922. Presumably Charles W. was the only one who moved to the US, the other two remained in Germany.

His wife Anna (Uhl) was born in 1850 and was only 36 when he died. Antoinette (Nettie) was 11 at the time and Carola exactly one year old.

Charles W. was close to his stepfather, Oswald Ottendorfer (1826-1900), who managed the Staats-Zeitung after his wife, Anna 1815-1884, became too ill to continue.

Oswald O. was 18 years older than Charles W. and was involved in Woerishoffer & Co.

MR. WOERISHOFFER'S WILL

Charles Frederick Woerishoffer made almost as short a will as possible. As has been stated in The Times the estate is left to relatives and the will is dated May 18, 1874. He gives $10'000 to his sister, Antonia Ammon, of Constanz, Germany. To Frederick Woerishoffer, a brother, living in Freiburg, Germany, a like sum is bequeathed. The remainder of the estate is left to the testator’s wife, Anna Woerishoffer. Charles Schierenberg is made Executor of the instrument and the widow Executrix. Probate Clerk Charles H. Beckett began taking testimony with a view to probating the will yesterday morning, but was compelled to adjourn the matter until Friday. Surrogate Rollins has appointed Robert Jackson special guardian for the two daughters of Mr. Woerishoffer, Emma Carola and Antoinette. As they were born after the execution of the will they will receive the same proportion of the estate as they would if there had been no will.

The New York Times

Published: May 25, 1886

Copyright © The New York Times

CHARLES FREDERICK WOERISHOFFER

CHARLES FREDERICK WOERISHOFFER, banker, originated in Glenhausen, province of Hesse, Germany, where he was born on 5th August 1844. He died in Manhattan on 10th May 1886. His family were worthy and reputable people but very poor and did not possess the means to give their boy a start in business life. Confronted with the stern struggle for existence at an early age, he was compelled to depend upon himself from boyhood; and this circumstance no doubt did much to develop the self-reliance, the habit of thinking for himself, and the enterprise, which distinguished his subsequent career.

Trained to the requirements of business in Frankfort and Paris, he sailed for the new world in 1865 [21 years old] to seek his fortune. Settling in New York City, he entered the office of August Rutten as a clerk. His native capacity brought him rapidly forward, and Mr Rutten soon made him the cashier. Not long after that, he pushed out for himself and in 1868 associated himself with M. C. Klingenfeld, and a year or so later with others, finally becoming a member of the Stock Exchange. He then transacted very important business for L. von Hoffman & Co., who found their trust in him amply repaid by his energetic, prudent and successful ways. With them, he began to lay the foundation of a fortune. Emboldened at last to engage in business under his own name, he established in the summer of 1870 [26 years old] the firm of Woerishoffer & Co., stock brokers and bankers. The house was prosperous from the start, and two of the original partners soon retired rich.

The firm have always been noted for their enterprise and influence. One of the operations which won reputation for Mr Woerishoffer was a fight he waged in 1879 with Jay Gould, Russell Sage and others for the control of the Kansas Railroad. Woerishoffer, representing a number of Frankfort investors, contracted to sell certain Denver bonds to the Gould-Sage syndicate for $ 80 on the hundred, but the latter repudiated the contract and named $ 70 as their price. Mr Woerishoffer made prompt and effective use of the telegraph cable to Europe, and before the syndicate had fully prepared for his campaign, he had safely gathered within the hand of the United States Trust Co., more than a majority of the bonds, which the syndicate were after. He then had the satisfaction of telling his rivals, calmly, that as their foreclosure scheme depended on securing control of the bonds, they would have to pay full price for their coquettishness. The syndicate failed to shake his determination and were obliged to pay par value for the bonds. This operation made Mr Woerishoffer famous in Germany and London as well as in New York. From that time forward he enjoyed the implicit trust of every investor in American securities; and as a result of that successful deal, Frankfort came largely into the New York stock market. About $ 86,000,000 were involved in the case.

Mr Woerishoffer was also identified with a famous campaign in Wall Street, over Northern Pacific Railroad securities. While the stock of that road ranged at a high price, he declared that the earnings of the company did not warrant the fancy quotations at which the stocks were held. With the courage of his convictions, he openly sold the whole line short, standing in this operation single-handed against many influential men and heavy bankers. Seeing that arguments were of no avail, his opponents decided to whip Mr Woerishoffer into line; and a syndicate was formed to buy 100,000 shares of the stock and squeeze him out of the market. That speculation proved a merry dance for the Street, but Mr Woerishoffer led the way. Nothing seemed to daunt him. No rise or fall in quotations provoked more than a look of indifference. Countless friends assured him that he stood on a volcano, which might wreck his fortunes and those of his friends. With a rush, the 100,000 shares were bid up to a high quotation. The whole order was filled by his own brokers, and he had cleared millions by his allegiance to the fact that stock cannot be sustained for any length of time with net earnings out of the question.

Mr Woerishoffer led to success a dozen noted campaigns which followed in Wall Street. He was conspicuous in The West Shore Railroad settlement, and his transactions in special speculations ranged at tremendous figures. Where others bought or sold thousands of shares, he handled tens and hundreds of thousands. Cool, reticent, and observing, he possessed a judgement of values intrinsic and speculative, which seldom erred and was usually exact. He knew all the resources of speculation and employed them with success both in bulling and bearing stocks. Operating through many different offices, his brokers were often ignorant of the fact that other members of the Stock Exchange, with whom they were at cross purposes, had the same client.

Fortune came to him in large operations, and his generosity was proverbial. His clerks were the envy of every office in Wall Street. Thousands went every month to help other men and Mr Woerishoffer is credited with the unexampled liberality of giving over twenty Stock Exchange seats, without reserve, to men whom he had found faithful to his interests. It was not exceptional for him to give $1,000 cheques as Christmas presents to the clerks. The charities of the city also received from him frequent and large contributions. To the German Hospital he was a large donor.

At the time of his death, he had been a power in Wall Street for over twenty years [? - he had arrived in the States in 1865 but only started ‘pushing for himself’ in 1868, which left him with 18 years to pull any weight financially]. His speculations were noted for their dash, fearlessness and success. No great operator in Wall Street was ever more popular among those with whom he came into contact. His life was full of dramatic incidents and his career in Wall Street paralleled by few. Starting as a poor clerk, without friends or influence in America, at the age of twenty-one, at forty-three he had risen to be a power in money centres, a ruler of corporations, a maker of markets and possessed of a fortune of millions. Every iota of his far-reaching influence he made for himself.

He retired from active partnership in the firm of Woerishoffer & Co. on 1st January 1886, but retained a special partnership and gave the succeeding firm the benefit of his frequent advice. He was also a special partner in the firm of Walsh & Hackman, at 27 William Street. In 1873, he was married to Anne, the daughter of the late Mrs Anne Ottendorfer. He had two daughters.

Hall, H.

‘America’s successful men of affairs’

2 volumes, 1895-96

in American Biographical Archive

Editor: Garance Worters

K. G. Saur London · New York · Munich · Paris

CHARLES FREDERICK WOERISHOFFER

CHARLES FREDERICK WOERISHOFFER, banker, originated in Glenhausen, province of Hesse, Germany, where he was born on 5th August 1844. He died in Manhattan on 10th May 1886. His family were worthy and reputable people but very poor and did not possess the means to give their boy a start in business life. Confronted with the stern struggle for existence at an early age, he was compelled to depend upon himself from boyhood; and this circumstance no doubt did much to develop the self- reliance, the habit of thinking for himself, and the enterprise, which distinguished his subsequent career.

Trained to the requirements of business in Frankfort and Paris, he sailed for the new world in 1865 [21 years old] to seek his fortune. Settling in New York City, he entered the office of August Rutten as a clerk. His native capacity brought him rapidly forward, and Mr Rutten soon made him the cashier. Not long after that, he pushed out for himself and in 1868 associated himself with M. C. Klingenfeld, and a year or so later with others, finally becoming a member of the Stock Exchange. He then transacted very important business for L. von Hoffman & Co., who found their trust in him amply repaid by his energetic, prudent and successful ways. With them, he began to lay the foundation of a fortune. Emboldened at last to engage in business under his own name, he established in the summer of 1870 [26 years old] the firm of Woerishoffer & Co., stock brokers and bankers. The house was prosperous from the start, and two of the original partners soon retired rich.

The firm have always been noted for their enterprise and influence. One of the operations which won reputation for Mr Woerishoffer was a fight he waged in 1879 with Jay Gould, Russell Sage and others for the control of the Kansas Railroad. Woerishoffer, representing a number of Frankfort investors, contracted to sell certain Denver bonds to the Gould-Sage syndicate for $80 on the hundred, but the latter repudiated the contract and named $70 as their price. Mr Woerishoffer made prompt and effective use of the telegraph cable to Europe, and before the syndicate had fully prepared for his campaign, he had safely gathered within the hand of the United States Trust Co., more than a majority of the bonds, which the syndicate were after. He then had the satisfaction of telling his rivals, calmly, that as their foreclosure scheme depended on securing control of the bonds, they would have to pay full price for their coquettishness. The syndicate failed to shake his determination and were obliged to pay par value for the bonds. This operation made Mr Woerishoffer famous in Germany and London as well as in New York. From that time forward he enjoyed the implicit trust of every investor in American securities; and as a result of that successful deal, Frankfort came largely into the New York stock market. About $ 86,000,000 were involved in the case.

Mr Woerishoffer was also identified with a famous campaign in Wall Street over Northern Pacific Railroad securities. While the stock of that road ranged at a high price, he declared that the earnings of the company did not warrant the fancy quotations at which the stocks were held. With the courage of his convictions, he openly sold the whole line short, standing in this operation single-handed against many influential men and heavy bankers. Seeing that arguments were of no avail, his opponents decided to whip Mr Woerishoffer into line; and a syndicate was formed to buy 100,000 shares of the stock and squeeze him out of the market. That speculation proved a merry dance for the Street, but Mr Woerishoffer led the way. Nothing seemed to daunt him. No rise or fall in quotations provoked more than a look of indifference. Countless friends assured him that he stood on a volcano, which might wreck his fortunes and those of his friends. With a rush, the 100,000 shares were bid up to a high quotation. The whole order was filled by his own brokers, and he had cleared millions by his allegiance to the fact that stock cannot be sustained for any length of time with net earnings out of the question.

Mr Woerishoffer led to success a dozen noted campaigns which followed in Wall Street. He was conspicuous in The West Shore Railroad settlement, and his transactions in special speculations ranged at tremendous figures. Where others bought or sold thousands of shares, he handled tens and hundreds of thousands. Cool, reticent, and observing, he possessed a judgement of values intrinsic and speculative, which seldom erred and was usually exact. He knew all the resources of speculation and employed them with success both in bulling and bearing stocks. Operating through many different offices, his brokers were often ignorant of the fact that other members of the Stock Exchange, with whom they were at cross purposes, had the same client.

Fortune came to him in large operations, and his generosity was proverbial. His clerks were the envy of every office in Wall Street. Thousands went every month to help other men and Mr Woerishoffer is credited with the unexampled liberality of giving over twenty Stock Exchange seats, without reserve, to men whom he had found faithful to his interests. It was not exceptional for him to give $1,000 cheques as Christmas presents to the clerks. The charities of the city also received from him frequent and large contributions. To the German Hospital he was a large donor.

At the time of his death, he had been a power in Wall Street for over twenty years [? - he had arrived in the States in 1865 but only started ‘pushing for himself’ in 1868, which left him with 18 years to pull any weight financially]. His speculations were noted for their dash, fearlessness and success. No great operator in Wall Street was ever more popular among those with whom he came into contact. His life was full of dramatic incidents and his career in Wall Street paralleled by few. Starting as a poor clerk, without friends or influence in America, at the age of twenty-one, at forty-three he had risen to be a power in money centres, a ruler of corporations, a maker of markets and possessed of a fortune of millions. Every iota of his far-reaching influence he made for himself.

He retired from active partnership in the firm of Woerishoffer & Co. on 1st January 1886, but retained a special partnership and gave the succeeding firm the benefit of his frequent advice. He was also a special partner in the firm of Walsh & Hackman, at 27 William Street. In 1873, he was married to Anne, the daughter of the late Mrs Anne Ottendorfer. He had two daughters, Antoinette and Emma Carola.

Hall, H. ‘America’s successful men of affairs’, 1895-96 in

American Biographical Archive, Editor: Garance Worters K. G. Saur London · New York · Munich · Paris

The Behr, Uhl, Woerishoffer and Ottendorfer families are buried in the Greenwood cemetery in Brooklyn.