New Yorker Staats-Zeitung

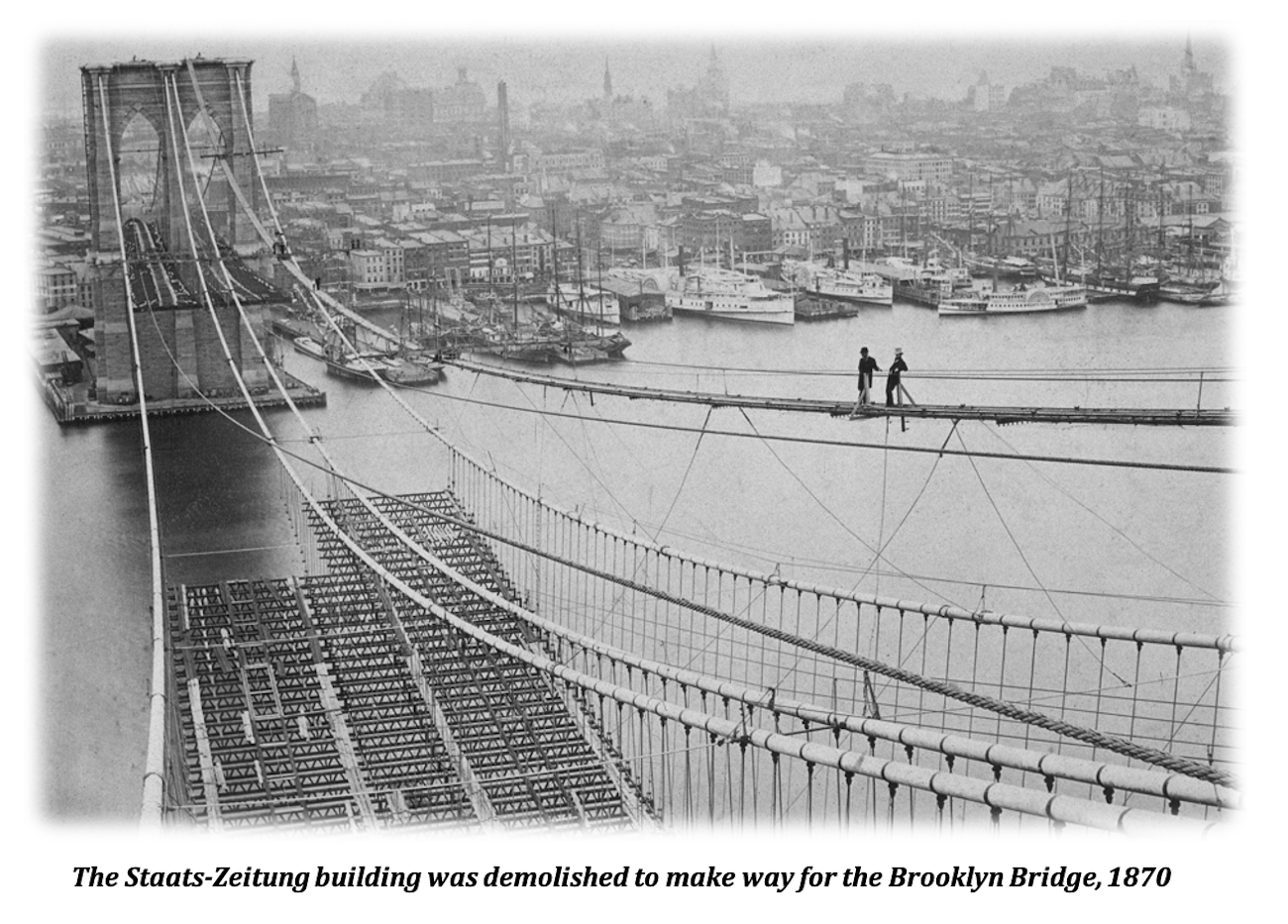

New York in the 1870s when the Staats-Zeitung was at its prime.

The Civil War (1861-1865) was over and a transcontinental railway newly completed, allowing easier passage from the East Coast to California.

People lit their houses with candles and whale oil, and heated them with wood or coal-burning stoves.

Only a quarter of the population lived in cities, most of them in the Northeast. Families were much larger in those days and 59 percent of the population was under age 25 (compared to 34 percent today).

Pork was the meat people ate the most because it was easily salted or smoked and could be preserved in an era without refrigeration.

Fresh vegetables were scarce; farmers emphasized crops that could be stored or preserved, like turnips, pumpkins, beans and potatoes, instead of leafy greens that would deteriorate quickly.

Apples were the only fruit widely consumed.

There was not much in the way of consumer goods, and department stores were in their infancy, just starting to appear in large cities.

Instead of a toilet, you used a chamber pot or an open window in the city (hard to believe!!). Modern toilets were an invention that was in its earliest phases during the 1870s. Big cities had sewers for both rainwater and human waste and they flowed into rivers unfiltered.

The New York subway first opened 1904.

There were around 250 horses per square kilometre. The average horse produced 25 kilos of manure and 4 litres of urine daily, which made the streets no pleasant place to be.

Total circulation of newspapers was 2.6 million in a country of 40 million people.

There was no telephone, record player, cinemas or radio. Men could go to the local saloon to drink; women generally couldn’t.

Vacations and weekends were only for the privileged.

History of a New York Institution

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Yorker_Staats-Zeitung

http://www.germancorner.com/NYStaatsZ/history.html

The city’s German Jacksonian Democrats launched the New Yorker Staats-Zeitung, nicknamed the “Staats” on December 24, 1834. After languishing under a series of owners, it was sold in 1845 to Jakob Uhl. Uhl, a native of Würzburg in Franconia, had been jailed for taking part in a democratic riot in Frankfurt in 1833, left for New York in 1835 and was hired as printer by the Staats the next year. In 1837, he married Anna Behr, 1815-1884, also from Würzburg.

Uhl supported the German revolution of 1848-1849 in his paper and collected funds. When he died in 1852, the Staats had become the foremost paper of the city's estimated 60,000 Germans, but this success also forced the Staats early on to adopt a centrist line towards divisive issues of the day, in contrast to the short-lived, radical German papers of that era.

Uhl supported the German revolution of 1848-1849 in his paper and collected funds. When he died in 1852, the Staats had become the foremost paper of the city's estimated 60,000 Germans, but this success also forced the Staats early on to adopt a centrist line towards divisive issues of the day, in contrast to the short-lived, radical German papers of that era.

In 1850, Uhl had hired Oswald Ottendorfer, 1826-1902, a Sudeten German from Zwittau in Moravia, who had fought in the German revolution. In 1859 he married Uhl's widow. Under his stewardship, the Staats flourished and became a daily in 1854. He also continued its liberal policy, and steered it through two great crises. During the long struggle over state rights and slavery, Ottendorfer, a Democrat by party affiliation, and opposed to centralized bureaucracies, supported a moderate position that was attacked by German Republicans.

Then, in 1866, the German Confederation fell apart. New York Germans split between partisans of a reunited Germany under Prussian leadership, even at the price of leaving out the 12 million Germans of the Habsburg Empire and those who, like Ottendorfer, were horrified. The split healed only after the German victory over the French Empire and the creation of a special alliance between Vienna and Berlin.

Then, in 1866, the German Confederation fell apart. New York Germans split between partisans of a reunited Germany under Prussian leadership, even at the price of leaving out the 12 million Germans of the Habsburg Empire and those who, like Ottendorfer, were horrified. The split healed only after the German victory over the French Empire and the creation of a special alliance between Vienna and Berlin.

The number of Germans in the city grew rapidly, as did their clubs and societies, while older immigrants and their children created an elite group that provided the necessary structure and leadership. Many new German papers were established. Despite the competition, the Staats remained the largest and even became the third largest daily in the city.

In 1886 the

| N.Y. World sold | 149,000 | copies a day |

| N.Y. Tribune | 80,000 | |

| New Yorker Staats-Zeitung | 60,000 | |

| N.Y. Times | 40,000 | |

| German-Republican Herold | 35,000 | |

| N.Y. Evening Post | 17,000 | |

| N.Y. Volkszeitung (socialist) | 10,000 |

In addition, there were scores of German-language weeklies and trade publications and in Brooklyn the large "Freie Presse." The Ottendorfer's belonged to the emerging German-American elite. They were active in local philanthropies. They built in 1875 the Isabella Home for the Aged, later the Ottendorfer branch of the New York Public Library and donated close to $500,000 to German hospitals in the city.

Oswald Ottendorfer also was active in local politics, running several times as reform mayoral candidate against corrupt Tammany Hall and nativist Republicans. He failed, but was elected several times presidential elector on the Democratic ticket. Ottendorfer had no children. Uhl's children, who owned the majority of the stock, were not interested in running the paper and to preserve the Staats, they decided to sell to Herman Ridder.

Oswald Ottendorfer also was active in local politics, running several times as reform mayoral candidate against corrupt Tammany Hall and nativist Republicans. He failed, but was elected several times presidential elector on the Democratic ticket. Ottendorfer had no children. Uhl's children, who owned the majority of the stock, were not interested in running the paper and to preserve the Staats, they decided to sell to Herman Ridder.

Ridder, 1851-1915, was born in New York of Westphalian parents. He grew up in poverty in the Lower East Side, but then made money selling life insurance. In 1878, he founded the weekly Katholisches Volksblatt and in 1886 the Catholic News. In 1890, Ridder was sold a tenth of the shares and made business manager. He acquired complete ownership in 1906. Like Ottendorfer, Ridder was a leading member of the German community and active in politics. He was an important member of the local Democratic Party, served as president of the American Newspaper Publishers' Association and in 1908 received the influential post of treasurer of the Democratic National Committee - the only publisher of an ethnic paper to ever hold either honour.

Although immigration from the Second German Empire had begun to shrink around 1900, Germans from the Habsburg Empire had replaced it. There would be no shortage of readers. Yet, around the same time storm clouds began to gather. The Progressive movement, popular among the still politically dominant Anglo-American middle-class, opposed pluralistic America. They wanted to eradicate the use of non-English languages in the country (and were especially offended by US-born German-speakers such as the Ridders), impose prohibition and ensure a foreign policy biased towards Great Britain. The Staats was a proud local symbol of opposition to all that. It was vilified, especially after the outbreak of World War I, for the Ridders fought British war-guilt and atrocity propaganda and collected relief for war victims in Central Europe. This was legal and perfectly proper partisanship. But it angered those Americans who believed that Germany was an evil empire and that to side with the "Huns" was un-American.

Victor Ridder died in November 1915. His sons Bernard, Victor and Joseph now steered the Staats through trying times. After April 1917, as most German-Americans, they took the position that since the legal government of the country had declared war, it must be supported, whatever one felt about the morality of that decision. But German-Americans were subjected to unprecedented persecution, described as "hysteria" in the memoirs of Treasury Secretary William Gibbs McAdoo.

As David Bennett, a historian at Syracuse University, noted, it became a sign of patriotism to stone the neighbourhood German butcher shop. The Staats, a much more visible target, was boycotted by advertisers and news dealers, and harassed by zealous agents of competing federal intelligence agencies, the Bureau of Investigation (Forerunner of the FBI) and the American Protective League, a vigilante group that cooperated with it, the Treasury Secret Service, the Military Intelligence Department, the Navy Intelligence Department and the nasty little secret service created by New York Attorney General Merton Lewis, a Republican, to tar the Democratic administration with softness towards sedition. In this witch-hunt, many German-American institutions perished. Only the sudden end of the war, and their connections to the city’s powerful democratic machine and Catholic Church saved the Ridders.

After the war, those German-American societies that had survived became active again. Their future looked reasonably bright, for there would be many immigrants from war-torn Europe, and little persecution as many Americans began to have second thoughts about the war. In New York, mayor Hylan presided over relief efforts for Germany and Austria as early as 1919, and spoke against the surreal terms of the Versailles Treaty. The German-American press would continue to wield influence, even if much less than before the war. And so the Ridders bought the Herold and other dailies that had not survived.

These hopes were dashed by the 1924 Immigration Act, which abolished free immigration and gave Central Europe only small quotas, while the public school system drastically cut the number of second-generation bilingual speakers. In 1926-1927, the Ridders purchased the Long Island Press and the Journal of Commerce, laying the foundation of the Knight-Ridder media conglomerate. The Staats became a side-line and was merged in 1934 with the Herold as the Staats-Zeitung und Herold. (Herold was dropped from the masthead in 1991). It still sold 80,000 copies a day in 1938, but was greatly harmed by World War II and the resulting prejudice against all things German, which could not be offset by the trickle of German immigration. In 1953 the Staats was sold to the Steuer family, became a thrice weekly, and then a weekly. In 1989 the Steuer family sold the Staats to Jes Rau, the former American correspondent of Die Zeit of Hamburg, Germany. Circulation declined slowly but inexorably as it did for the older ethnic press in general. Still, the Staats remains the premier German-American paper, and the sole outlet for German-Americans of New York, Florida and Philadelphia, since the English-language press does not report much about them. For instance Governor George Pataki and Senator Alfonse D'Amato marched at the Steuben Parade in New York in 1995. They knew it was a major occasion to show respect to a still noteworthy group of voters, and Giuliani and D'Amato have marched for several years. Recent grand marshals were Eric Braeden, the actor and Cardinal O'Connor. But what did the "newspaper of record" of the city tell its readers about this event? The New York Times' sole feature about the parade was the picture of a girl herding a goose, taken, it seems, in the early 1960s. As you can see, one still needs the Staats-Zeitung to get the full picture!

copyright © 1997 New Yorker Staats-Zeitung

From another source:

Anna Uhl Ottendorfer, business manager 1845-1884. German immigrants founded the Staats-Zeitung in 1834. Jacob Uhl purchased the newspaper in 1845, at that point a weekly paper with very limited circulation edited by Gustav Adolph Neuman.

Jacob Uhl, with his wife, Anna, who worked as compositor, secretary and general manager, immediately enlarged the sheet and shortly developed it into a daily newspaper. When Jacob Uhl died in 1852, Anna Uhl took over management of the newspaper, with the assistance of Oswald Ottendorfer, who had been hired in the counting room. In 1858 Ottendorfer became editor and in 1859, aged 33, he married Anna Uhl who was 11 years older than him.

Anna Ottendorfer continued as business manager until shortly before her death in 1884 when her son Edward Uhl succeeded her. Together Anna and Oswald Ottendorfer developed the Staats-Zeitung into a major newspaper. By the 1870s, its circulation was comparable to English-language newspapers like the New York Tribune and the New York Times.

The New Yorker Staats-Zeitung flourished under the management of Oswald Ottendorfer and was sold to Ridder Publications in 1892, a company set up by Hermann Ridder for this purpose. As anti-German sentiment increased between the two world wars, Ridder successfully transitioned into English language publishing by acquiring the Journal of Commerce in 1926.

Note:

Ridder Publications merged with Knight Newspapers in 1974 to become Knight Ridder. In 2006, The McClatchy Company (ticker symbol MNI) announced its agreement to purchase Knight Ridder for $6.5 billion (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Knight_Ridder).

History

The Staats-Zeitung was founded in New York City in 1834 by a society of German-American businessmen. The partners included George Zahm, Stepan Molitor, Conrad Braeker, and Gustav Adolph Neumann, with Neumann serving as editor-in-chief (as well as reporter and production foreman). Neumann subsequently purchased shares of the enterprise until, in the late 1830s, he obtained a majority, after which the society was dissolved and he became sole owner.

The first issue was published on December 24, 1834. The nascent newspaper consisted of four pages and was printed weekly using a Washington hand-press. Initial circulation was small, limited by the capacity of the press (2000 impressions per day) and by the size of the audience (primarily German immigrants). At that time there were approximately 10,000 German-born citizens in New York City.

Growth during the first few years of the paper's existence was also impeded by the Financial Panic of 1837, but by 1839 it was sufficiently successful to move to a location on Frankfort Street, a few blocks from City Hall. Under Neumann's guidance, improvements to the physical plant were undertaken to support the growth that accompanied its increasing influence. In 1843, on obtaining a single cylinder hand-operated press that could print 600 sheets per hour, he converted the Staats-Zeitung to a tri-weekly publication.

The paper's staff also expanded as it grew. Notable additions included: Jacob Uhl, who may have been hired as a printer as early as 1836; Jacob's wife Anna Uhl, who worked as a compositor, secretary, and business manager and Oswald Ottendorfer, who appears to have been hired in the counting room in 1850. All had a role to play in the unfolding story.

In 1845 Jacob Uhl bought ownership and publishing rights from Neumann who, nonetheless, continued in an editorial capacity until 1853. Working together, Jacob and Anna Uhl increased both advertising patronage and circulation, enabling a shift to daily publication not long after the purchase. Subsequently, the paper's physical plant was moved to and combined with a printing office owned by Jacob Uhl, and a Sunday edition was added on January 3, 1848. The enhanced paper quickly outgrew both the press capabilities and the physical space of the printing office, and in 1850 Uhl purchased property specifically to house the Staats-Zeitung'". He installed the most rapid printing presses then available in a new building erected on the property for that purpose.

In 1845 Jacob Uhl bought ownership and publishing rights from Neumann who, nonetheless, continued in an editorial capacity until 1853. Working together, Jacob and Anna Uhl increased both advertising patronage and circulation, enabling a shift to daily publication not long after the purchase. Subsequently, the paper's physical plant was moved to and combined with a printing office owned by Jacob Uhl, and a Sunday edition was added on January 3, 1848. The enhanced paper quickly outgrew both the press capabilities and the physical space of the printing office, and in 1850 Uhl purchased property specifically to house the Staats-Zeitung'". He installed the most rapid printing presses then available in a new building erected on the property for that purpose.

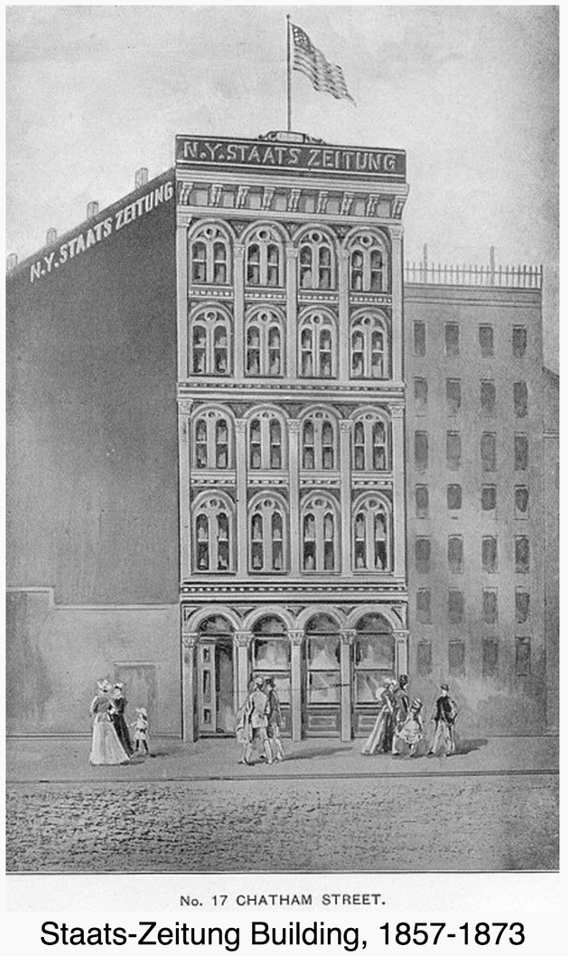

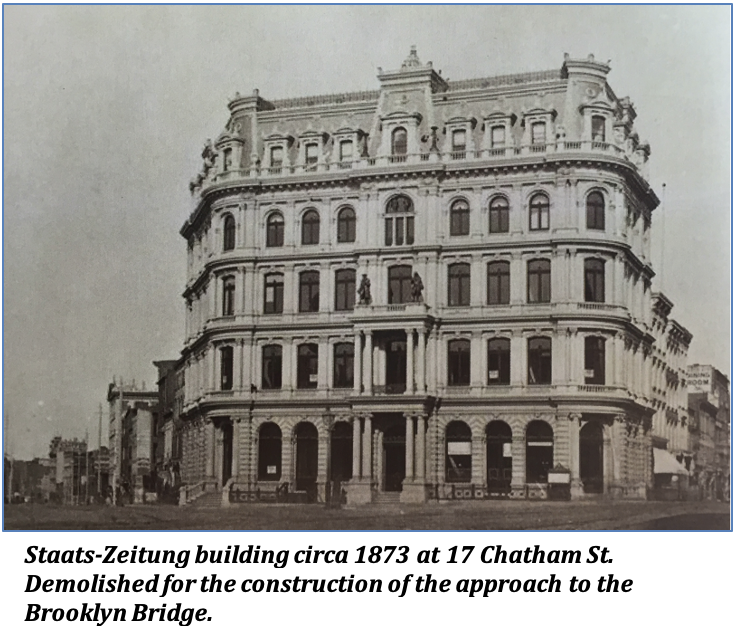

When Jacob Uhl died in 1852, Anna Uhl took over management of the newspaper. The paper continued to thrive, and by 1857 another expansion was required. Anna Uhl purchased property on what was then Chatham Street (also known at that time as "Newspaper Row", now Park Row) and had a suitable building erected. One of the first rotary type-revolving presses was installed, increasing the publishing capacity to 4,000 papers per hour.

In 1858, Anna Uhl appointed Oswald Ottendorfer - who had gradually been contributing more assistance - as editor. In 1859 Anna Uhl and Oswald Ottendorfer were married, and continued to operate the paper together, with Oswald serving as editor and publisher while Anna functioned as business manager. In 1873 another expansion was completed under the German-American architect J. William Schickel at 17 Chatham Street. Anna Ottendorfer continued as business manager until shortly before her death in 1884 when her son Edward Uhl succeeded her. Together Anna and Oswald Ottendorfer developed the Staats-Zeitung into a major newspaper. By the 1870s, its circulation was comparable to English-language newspapers like the New York Tribune and the New York Times.

In 1879, the property of the paper was changed into a stock company. When Oswald Ottendorfer died in 1900, the newspaper was sold to Herman Ridder, who had become manager and trustee in 1890. Ridder went on to contribute to the foundation of the Knight Ridder conglomerate, and the Staats-Zeitung gradually became a side line. It stayed in the Ridder family until 1953, when it was sold to the Steuer family who changed from a daily newspaper to three times a week and finally a weekly. In 1989, it was sold to Jes Rau.

From 1968 to 1969, the German entertainer and comedian Herbert Feuerstein was editor-in-chief of the newspaper.

Political influence

The German American businessmen who founded the New Yorker Staats-Zeitung in 1834 did so with a specific agenda in mind. The paper was to be the voice of German-Americans who opposed the Whig Party, then the dominant political force in New York City. This stance aligned the paper with the objectives of the Jacksonian Democrats, who were at that time developing the Tammany Hall political machine. Mr. Neumann's editorials took forceful and animated positions in support of the interests of German American immigrants who sought to become full participants in the governance of their new home.

However, the paper was also concerned with events in Europe, undoubtedly because German immigration at this time was often motivated by political repression in Germany. Jacob Uhl, for example, is said to have left Germany a year or two after being jailed for participating in a democratic riot in Frankfurt. As owner of the paper, he supported the German Revolution of 1848. Oswald Ottendorfer was an active participant in those European uprisings - in 1848 in Vienna and in 1849 in Saxony. His passion for things political remained after he immigrated to America, and he continued to develop the political clout of the Staats-Zeitung after he became editor in 1858.

From 1860 to 1864, Franz Umbscheiden - who also participated in the German Revolution of 1848 - was on the staff.

During World War II, the paper had an evolving view of Adolf Hitler and the Third Reich. In 1934, the Staats-Zeitung opposed the "mock trial" of Hitler to be held at Madison Square Garden, calling Nazi Germany a "friendly nation" and asking the U.S. to respect "the laws and deeds of the statutory regime of the German Reich; the laws and deeds of the lawful administration of government of a friendly power.[11] A year earlier, however, the paper published an editorial, entitled "Blind Fanatism" and signed by its then editor, Benjamin F. Ridder, denouncing the Nazi persecution of Jews. Later, the paper revealed a strongly anti-Nazi position, publishing many anti-Nazi editorials and articles, until Nazi party member Heinz Spanknöbel stormed the paper's office and forced the editors to write Nazi-sympathetic articles.

Today

The New Yorker Staatszeitung flourished under the management of Oswald Ottendorfer and was sold to Ridder Publications in 1892, a company set up by Hermann Ridder for this purpose. As anti-German sentiment increased between the two world wars, Ridder successfully transitioned into English language publishing by acquiring the Journal of Commerce in 1926.

Ridder Publications merged with Knight Newspapers in 1974 to become Knight Ridder.

In 2006, The McClatchy Company (ticker symbol MNI) announced its agreement to purchase Knight Ridder for $6.5 billion

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Knight_Ridder

Previous: Oswald Valentin Ottendorfer | Table of contents | Next: Green-wood Cemetery, Brooklyn