New Yorker Staats-Zeitung

1857

1870

Life in New York in the 1870s

The following gives an idea of what life was like at the time the New Yorker Staats-Zeitung was in its prime.

The Civil War (1861-1865) was over and a transcontinental railway newly completed, allowing easier passage from the East Coast to California.

People lit their houses with candles and whale oil, and heated them with wood or coal- burning stoves.

Only a quarter of the population lived in cities, most of them in the Northeast. Families were much larger in those days and 59% of the population was under age 25, compared to 34% today.

Apples were the only fruit widely consumed.

Apples were the only fruit widely consumed.

Pork was the meat people ate the most because it was easily salted or smoked and could be preserved in an era without refrigeration.

Fresh vegetables were scarce; farmers emphasized crops that could be stored or preserved, like turnips, pumpkins, beans and potatoes, instead of leafy greens that would deteriorate quickly.

There was not much in the way of consumer goods, and department stores were in their infancy, just starting to appear in large cities.

Instead of a toilet, you used a chamber pot or an open window in the city (hard to believe!). Modern toilets were an invention that was in its earliest phases during the 1870s. Big cities had sewers for both rainwater and human waste which flowed into rivers unfiltered.

The New York subway first opened 1904.

There were around 250 horses per square kilometer. The average horse produced 25 kilos of manure and 4 liters of urine daily, which made the streets no pleasant place to be.

Total circulation of newspapers was 2.6 million in a country of 40 million people.

There was no telephone, record player, cinemas or radio. Men could go to the local saloon to drink; women generally couldn’t.

Vacations and weekends were only for the privileged.

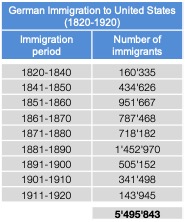

19th century German Immigration

The largest flow of German immigration to America occurred between 1820 and World War I, during which time nearly six million Germans immigrated to the United States. From 1840 to 1880, they were the largest group of immigrants. Following the Revolutions of 1848 in the German states, a wave of political refugees fled to America, who became known as Forty-Eighters. They included professionals, journalists, and politicians. Prominent Forty-Eighters included Carl Schurz and Henry VillardJ551

The largest flow of German immigration to America occurred between 1820 and World War I, during which time nearly six million Germans immigrated to the United States. From 1840 to 1880, they were the largest group of immigrants. Following the Revolutions of 1848 in the German states, a wave of political refugees fled to America, who became known as Forty-Eighters. They included professionals, journalists, and politicians. Prominent Forty-Eighters included Carl Schurz and Henry VillardJ551

"Latin farmer" or Latin Settlement is the designation of several settlements founded by some of the Dreissiger and other refugees from Europe after rebellions like the Frankfurter Wachensturm beginning in the 1830s¬predominantly in Texas and Missouri, but also in other U.S. states-in which German intellectuals (freethinkers, German:

Freidenker, and Latinists, met together to devote themselves to German literature, philosophy, science, classical music, and the Latin language.

HISTORY OF A NEW YORK CITY INSTITUTION

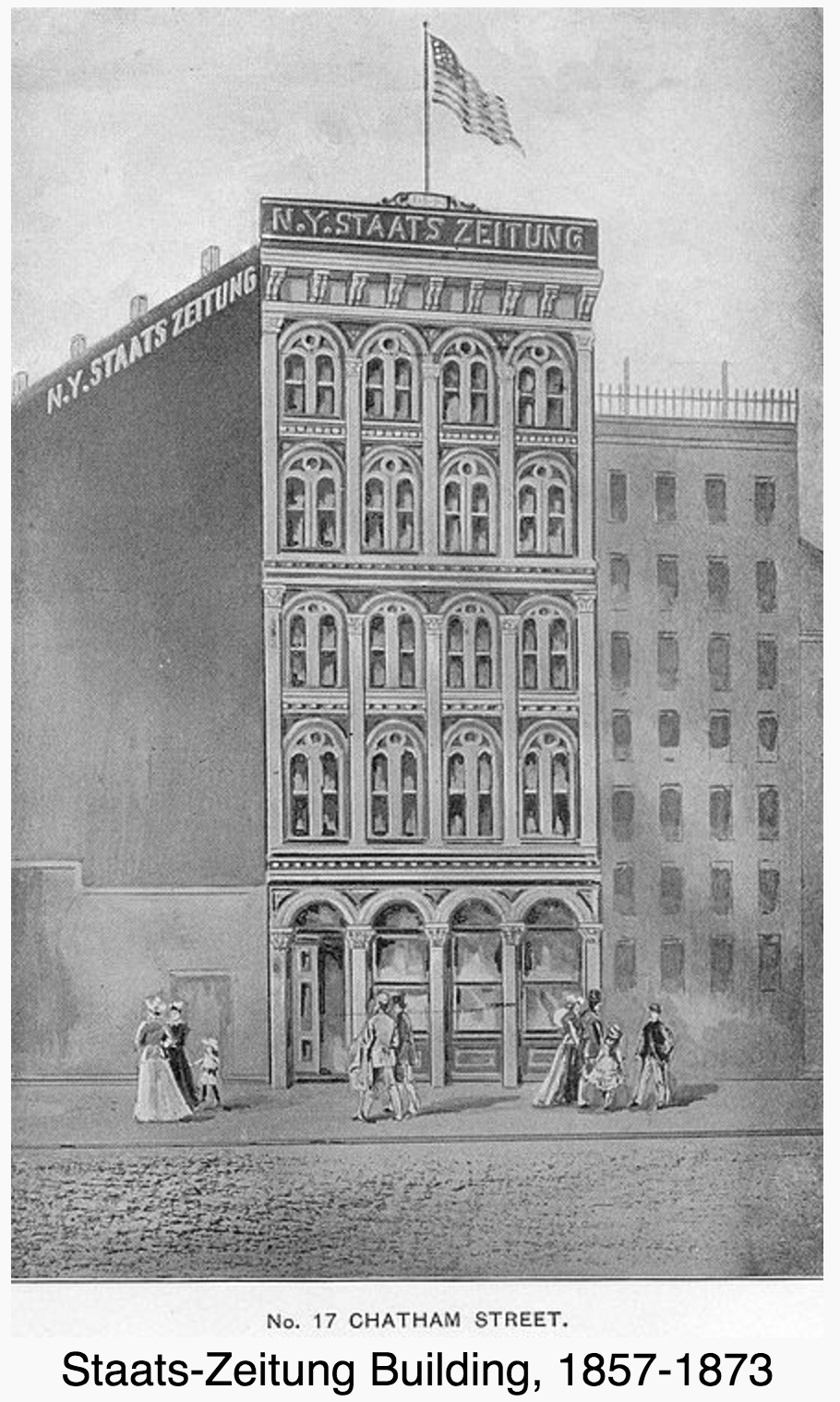

The city’s German Jacksonian Democrats launched the New Yorker Staatszeitung, nicknamed the “Staats,” on December 24, 1834. After languishing under a series of owners, it was sold in 1845 to Jakob Uhl. Uhl, a native of Würzburg in Franconia, had been jailed for taking part in a democratic riot in Frankfurt in 1833, left for New York in 1835 and was hired as printer by the Staats the next year. In 1837, he married Anna Behr, 1815-1884, also from Würzburg. Uhl supported the German revolution of 1848-1849 in his paper and collected funds. When he died in 1852, the Staats had become the foremost paper of the city's estimated 60,000 Germans, but this success also forced the Staats early on to adopt a centrist line towards divisive issues of the day, in contrast to the short-lived, radical German papers of that era.

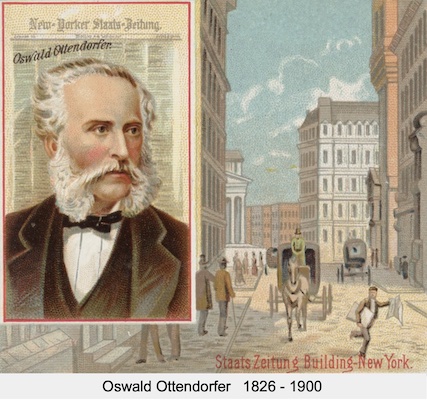

In 1850, Uhl had hired Oswald Ottendorfer, 1826-1902, a Sudeten German from Zwittau in Moravia, who had fought in the German revolution. In 1859, he married Uhl's widow. Under his stewardship, the Staats flourished and became a daily in 1854. He also continued its liberal policy and steered it through two great crises. During the long struggle over state rights and slavery, Ottendorfer, a Democrat by party affiliation, and opposed to centralized bureaucracies, supported a moderate position that was attacked by German Republicans. Then, in 1866, the German Confederation fell apart. New York Germans split between partisans of a reunited Germany under Prussian leadership, even at the price of leaving out the 12 million Germans of the Habsburg Empire and those who, like Ottendorfer, were horrified. The split healed only after the German victory over the French Empire and the creation of a special alliance between Vienna and Berlin.

The number of Germans in the city grew rapidly, as did their clubs and societies, while older immigrants and their children created an elite group that provided the necessary structure and leadership. Many new German papers were established. Despite the competition, the Staats remained the largest and even became the third largest daily in the city.

| N.Y. World sold | 149,000 copies a day |

| N.Y. Tribune | 80,000 |

| New Yorker Staatszeitung | 60,000 |

| N.Y. Times | 40,000 |

| German-Republican Herold | 35,000 |

| N.Y . Evening Post | 17,000 |

| N.Y. Volkszeitung (socialist) | 10,000 |

In addition, there were scores of German-language weeklies and trade publications and in Brooklyn the large "Freie Presse." The Ottendorfer's belonged to the emerging German American elite. They were active in local philanthropies. They built in 1875 the Isabella Home for the Aged, later the Ottendorfer branch of the New York Public Library and donated close to $500,000 to German hospitals in the city. Oswald Ottendorfer also was active in local politics, running several times as reform mayoral candidate against corrupt Tammany Hall and nativist Republicans. He failed but was elected several times presidential elector on the Democratic ticket. Ottendorfer had no children. Uhl's children, who owned the majority of the stock, were not interested in running the paper.

To preserve the StaatsZeitung, they decided to sell to Herman Ridder.

Ridder, 1851-1915, was born in New York of Westphalian parents. He grew up in poverty in the Lower East Side, but then made money selling life insurance. In 1878, he founded the weekly Katholisches Volksblatt and in 1886 the Catholic News. In 1890, Ridder was sold a tenth of the shares and made business manager. He acquired complete ownership in 1906. Like Ottendorfer, Ridder was a leading member of the German community and active in politics. He was an important member of the local Democratic Party, served as president of the American Newspaper Publishers' Association and in 1908 received the influential post of treasurer of the Democratic National Committee - the only publisher of an ethnic paper to ever hold either honour. Although immigration from the Second German Empire had begun to shrink around 1900, Germans from the Habsburg Empire had replaced it. There would be no shortage of readers. Yet, around the same time storm clouds began to gather.

The Progressive movement, popular among the still politically dominant Anglo-American middle-class, opposed pluralistic America. They wanted to eradicate the use of non-English languages in the country, <and were especially offended by US-born German-speakers such as the Ridders>, impose prohibition, and ensure a foreign policy biased towards Great Britain. The Staats was a proud local symbol of opposition to all that. It was vilified, especially after the outbreak of World War I, for the Ridders fought British war-guilt and atrocity propaganda and collected relief for war victims in Central Europe. This was legal and perfectly proper partisanship. But it angered those Americans who believed that Germany was an evil empire and that to side with the "Huns" was un- American.

Victor Ridder died in November 1915. His sons Bernard, Victor and Joseph now steered the Staats through trying times. After April 1917, as most German- Americans, they took the position that since the legal government of the country had declared war, it must be supported, whatever one felt about the morality of that decision.

But German-Americans were subjected to unprecedented persecution, described as "hysteria" in the memoirs of Treasury Secretary William Gibbs McAdoo. As David Bennett, a historian at Syracuse University, noted, it became a sign of patriotism to stone the neighborhood German butcher shop. The Staats, a much more visible target, was boycotted by advertisers and news dealers, and harassed by zealous agents of competing federal intelligence agencies, the Bureau of Investigation (Forerunner of the FBI) and the American Protective League, a vigilante group that cooperated with it, the Treasury Secret Service, the Military Intelligence Department, the Navy Intelligence Department and the nasty secret service created by New York Attorney General Merton Lewis, a Republican, to tar the Democratic administration with softness towards sedition. In this witch-hunt, many German American institutions perished. Only the sudden end of the war, and their connections to the city’s powerful democratic machine and Catholic Church saved the Ridders.

After the war, those German American societies that had survived became active again. Their future looked reasonably bright for there would be many immigrants from war-torn Europe, and little persecution as many Americans began to have second thoughts about the war. In New York, mayor Hylan presided over relief efforts for Germany and Austria as early as 1919 and spoke against the surreal terms of the Versailles Treaty. The German American press would continue to wield influence, even if much less than before the war. And so the Ridders bought the Herold and other dailies that had not survived.

These hopes were dashed by the 1924 Immigration Act, which abolished free immigration and gave Central Europe only small quotas, while the public school system drastically cut the number of second-generation bilingual speakers. In 1926- 1927, the Ridders purchased the Long Island Press and the Journal of Commerce, laying the foundation of the Knight-Ridder media conglomerate. The Staats became a sideline and was merged in 1934 with the Herold as the Staatszeitung und Herold. (Herold was dropped from the masthead in 1991). It still sold 80,000 copies a day in 1938 but was greatly harmed by World War II and the resulting prejudice against all things German, which could not be offset by the trickle of German immigration. In 1953, the Staats was sold to the Steuer family, became a thrice weekly, and then a weekly. In 1989 the Steuer family sold the Staats to Jes Rau, the former American correspondent of Die Zeit of Hamburg, Germany. Circulation declines slowly but inexorably---as it does for the older ethnic press in general. Still, the Staats remains the premier German American paper, and the sole outlet for German Americans of New York, Florida and Philadelphia, since the English-language press does not report much about them. For instance, Governor George Pataki and Senator Alfonse D'Amato marched at the Steuben Parade in New York in 1995. They knew it was a major occasion to show respect to a still noteworthy group of voters, and Guliani and D'Amato have marched for several years. Recent grand marshals were Eric Braeden, the actor and Cardinal O'Connor. But what did the "newspaper of record" of the city tell its readers about this event? The New York Times' sole feature about the parade was the picture of a girl herding a goose, taken, it seems, in the early 1960s. As you can see, one still needs the Staatszeitung to get the full picture!

copyright © 1997 New Yorker Staats-Zeitung

New Yorker Staats-Zeitung - Wikipedia

![]() Open New Yorker Staats-Zeitung - Wikipedia in PDF

Open New Yorker Staats-Zeitung - Wikipedia in PDF